Читать книгу Britain: The Lake District - Vivienne Crow - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

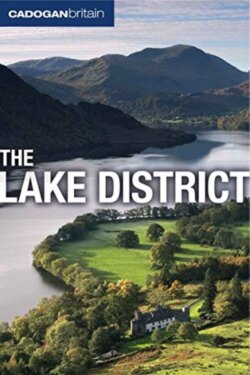

The Wonder of it All – Tourists Arrive

ОглавлениеFew braved the wilds of Cumberland and Westmorland purely for the pleasure of it before the second half of the 18th century. Celia Fiennes, who undertook a horseback journey through the region in 1698, came across a miserable corner of the country:

‘Here I came to villages of sad little hutts made up of drye walls, only stones piled together and the roofs of same slatt; there seemed to be little or noe tunnells for their chimneys and have no morter or plaister within or without; for the most part I tooke them at first sight for a sort of houses or barns to fodder cattle in, not thinking them to be dwelling houses, they being scattering houses here one there another, in some places there may be 20 or 30 together, and the Churches the same. It must needs be very cold dwellings but it shews something of the lazyness of the people; indeed here and there there was a house plaister'd, but there is sad entertainment, that sort of clap bread and butter and cheese and a cup of beer all one can have, they are 8 mile from a market town and their miles are tedious to go both for illness of way and length of the miles.’

The improvement of the turnpike roads in the middle of the century brought the first travellers, soon to be inspired by Fathter Thomas West’s A Guide to the Lakes, published in 1778. But it was only with the opening of the railways in the 19th century that travel ceased to be the preserve of only the wealthiest in British society.

The prospect of railways and mass tourism wasn’t to everyone’s liking though. The Romantic poet William Wordsworth, who was born and lived in the county (see Literary Lakeland, here), feared the ‘influx of strangers’ would destroy the area’s tranquillity and threaten the morals of local people. His protests, and those of other conservationists and local landowners, didn’t stop the Kendal and Windermere Railway from penetrating the Lake District proper, although it didn’t reach the lake itself; the line was terminated at Birthwaite, soon renamed Windermere, almost a mile from the lakeshore. The artist and social critic John Ruskin, another wealthy resident of the district, continued in that inimitably patronizing tone of the Victorian middle classes when, in the 1870s, there was an attempt to extend the railway line from Windermere to Keswick. Speaking of the potential tourists and fearing their moral character, he said: ‘I do not wish them to see Helvellyn when they are drunk’.

But see Helvellyn they did, whether drunk or sober, and they saw it in ever-increasing numbers; numbers that continued to rise with the advent of the motor car in the 20th century and are still rising today.