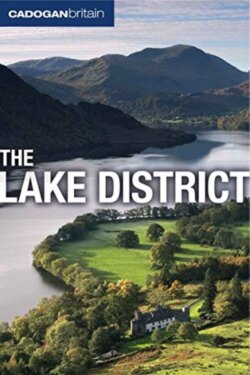

Читать книгу Britain: The Lake District - Vivienne Crow - Страница 36

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Glaciation

ОглавлениеIf the bedrock formed the raw material of the Lake District – the potter’s clay or the sculptor’s stone, so to speak – and the mountain-building periods associated with plate movement roughly moulded it into shape, it was the glaciers that put the finishing touches, that carved and sculpted the land into what we know and love today.

About 2.6 million years ago, the Earth began to cool, and glaciers formed, covering huge areas of land with massive ice sheets. People tend to refer to this, in very general terms, as the ‘Ice Age’, but within this ‘Ice Age’, there were cold periods (glacials) and warmer periods (inter-glacials) when forests thrived. There may have been as many as 11 cold phases, but it is the last one, which ended about 10,000 years ago, that had the most profound effect on the Lake District’s landscape. Glaciers formed in the central part of the Lake District and produced the radial drainage pattern – like the spokes of a wheel – present today.

The glaciers gouged out deep, u-shaped valleys and created arêtes, waterfalls in hanging valleys and long, narrow lakes held back by terminal moraine – a pile of clay and stone abandoned by the retreating ice. High in the mountains, the ice plucked out corries, which are now home to bodies of water known as tarns.

Glaciation also played a key role in the limestone landscapes that we see in south and east Cumbria. The formation of limestone pavement began when thick, heavy glaciers scoured the rock and fractured it along existing horizontal lines of weakness known as bedding planes. As the ice sheets retreated, they left a layer of boulder clay on the limestone, and, on top of this, soil formed. Since the end of the last glacial period, water has been exploiting the bedding planes as well as other cracks in the limestone. Over time, it has created the pattern of blocks (clints) and fissures (grikes) that we see at places such as Great Asby near Orton and on Whitbarrow today. These features became visible only after the soil on the top of the limestone platform was eroded, a process that increased with human activities such as forest clearance and grazing.

Landscape Terms

Arête: A narrow mountain ridge or spur formed by glaciation

Beck: Local word for a river or stream, from the Norse ‘bekkr’

Corrie: A steep-walled, amphitheatre-like hollow carved out of the mountain by a glacier. Also known as a cirque, cwm or coombe

Drumlin: A small, elongated hill or ridge formed from glacial deposits

Erratics: Large boulders dragged by glaciers and then dumped miles from where they were first picked up

Fell: Local word for a hill or mountain, from the Norse ‘fjall’ or ‘fjell’

Force: Local word for a waterfall, from the Norse ‘foss’

Ghyll or gill: Local word for a ravine, from the Norse ‘gil’

Hause: Local word for a pass or col, from the Norse ‘hals’

Holm: Local word for an island, from the Norse ‘holmr’

Moraine: Piles of boulders, stones and other debris deposited by a receding glacier

Scree: Loose piles of broken rock on mountain slopes

Tarn: A small body of water usually found in a corrie, from the Norse ‘tjorn’