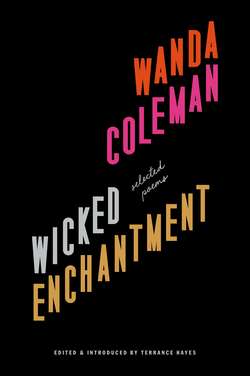

Читать книгу Wicked Enchantment - Wanda Coleman - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Wanda in Her Own Words

ОглавлениеIn addition to her many volumes of poetry, Wanda Coleman wrote several incredible books of prose, fiction, and nonfiction. And while I’ll leave it to the prose writers to bring her dazzling selected prose to the world, I do want to offer you some of my favorite of her autobiographical passages from her terrific nonfiction collection, The Riot Inside Me, published by Black Sparrow in 2005.—TH

“Jabberwocky Baby,” page 6

The stultifying intellectual loneliness of my 1950’s and 60’s upbringing was dictated by my looks—dark skin and unconkable kinky hair. Boys gawked at me, and girls tittered behind my back. Black teachers shook their heads in pity, and White teachers stared in amusement or in wonder. I found this rejection unbearable and encouraged by my parents to read, sought an escape in books, which were usually hard to come by.

“My Blues Love Affair,” page 20

In the 70s divorced and on my own, I danced at the discoes, dug on Black Sabbath, David Bowie, and Alice Cooper; I interviewed Bob Marley (Catch a Fire) on three occasions and made the St. Patrick’s Day Riots at Elks Hall when New Wave stormed Los Angeles . . . yet I began wearing the grooves off my Bobby “Blue” Bland. Taj Mahal, and Otis Redding LPs . . . I was a devotee of Herbie Hancock (Hornets), thrice catching him crosstown at Dough Weston’s Troubadour . . . While listening, I am able to visualize fingering, particularly piano and guitar, instruments I’ve studied.

“Angela’s Big Night,” pages 46–47

Los Angeles Free Press, LA’s controversial 60’s underground newspaper, gave me my first official freelance reporting assignment: covering a legal defense fundraiser for the then-incarcerated Black Power Movement heroine Angela Davis . . . As a result of my report, I would be secretly boycotted from journalism for the next ten years.

“Primal Orb Density,” page 55

Here I am. I prize myself greatly I want the world to enjoy me and my art but something’s undeniably wrong, I’ve come to regard myself as a living, breathing statistic governed not by my individual will, but by forces outside myself.

“Primal Orb Density,” page 65

My delicious dilemma is language. How I structure it. How the fiction of history structures me. And as I’ve become more and more shattered, my tongue has become tangled . . . I am glassed in by language as well as by the barriers of my dark skin and financial embarrassment.

“Looking for it: An interview,” page 77

My parents were petit bourgeoisie. My mother was a domestic—she came to California from Oklahoma when World War II started and jobs opened up for Blacks here. She worked in movie stars’ homes, and in fact worked a year for Ronald Reagan when he was married to Jane Wyman—she quit when he wouldn’t give her a raise! [Laughs.]

“Looking for It: An Interview,” page 91

My anger knows no bounds—it’s unlimited. I’m a big lady, I can stand up in front of almost any man and cuss him out and have no fear—you know what I’m sayin’? Because I will go to blows.

“Looking for It: An Interview,” page 93

I’m not about shock; if any shock is present it’s the shock of recognition . . . or the shock of understanding . . . But I’m not deliberately out to just shock people. I’m not about being sensationalistic . . . I want freedom when I write, I want the freedom to use any kind of language—whatever I feel is appropriate to get the point across.

“Coulda Shoulda Woulda: A Song Flung Up to Heaven by Maya Angelou,” page 137

I vented my bias against celebrity autobiographies at the outset of a favorable review of Angelou’s All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes (book review, August 13, 1986), in which I stated that I usually find them “self-aggrandizements and/or flushed-out elaborations of scanty press packets.” Relieved, I summarized Shoes as “a thoroughly enjoyable segment from the life of a celebrity!” No can do with Song.

“Black on Black: Fear & Reviewing in Los Angeles,” page 141

The night of the NBA [National Book Award] ceremony, it felt strange to hear my name (I was poetry finalist) called out from the podium by Steve Martin . . . I had devoted my best writing life to the financial wasteland of poetry, working pink-collar jobs to feed my children . . .

“Dancer on a Blade: Deep Talk, Revisions & Reconsiderations,” page 171

There are moments when I’m inclined to believe that trying to define poetry is as fruitless as trying to define love. It simply can’t be gotten right.

“Dancer on a Blade: Deep Talk, Revision & Reconsiderations,” page 180

My memory of the specifics is vague, but in 1972 I attended Diane Wakoski’s poetry workshop at California Technical Institute in Pasadena. I had met John Martin, the publisher of Black Sparrow Press, in March of that year, and he had strongly recommended I study with his “superstar” poet, author of Motorcycle Betrayal Poems . . . Diane Wakoski took me steps further toward enlightenment, as I kicked and ranted unable to fully articulate my point of view, stubborn in my stance but absorbing as much information as she could supply . . . Not least of the benefits of participating in Wakowski’s workshop was my friendship with poet Sylvia Rosen.

“Dancer on a Blade: Deep Talk, Revision & Reconsiderations,” page 205

Buying books was a great luxury in those days. What I couldn’t borrow and return or obtain from the public library, I read straight off bookstore shelves.

“Dancer on a Blade: Deep Talk, Revision & Reconsiderations,” page 206

I dared and mailed my painfully retyped manuscript to Black Sparrow Press. In March 1972, the manuscript was returned. Responding to my eagerness to learn, publisher John Martin steered me first to Wakoski and months later, to Clayton Eshleman. In the meantime I had become a Bukowski fan, trying to imitate his style, going to his readings, and hanging out at the infamous Bukowski parties . . . But it didn’t take too long to realize that my approach to language was, at root, radically different from Bukowski’s . . . Bukowski was tone deaf. And I loved the musical lyricism of writers like Neruda, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Brother Antoninus (a/k/a William Everson, who would eventually displace Bukowski as my favorite). I was also enthralled with the plays and poetry of Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones).

“Wearing My Maturity,” page 239

The characteristics many attribute to the supernatural have always been a natural/given part of how I am in the world. My intelligence. I have grown more comfortable with this as I’ve aged.

“The Riot Inside Me,” page 256

In 1991, following the death of my father, I took a major risk and quit my “slave” as medical secretary, encouraged by my third husband of ten years. The pull of my gift could no longer be denied. I had to write—regardless. I was in my mid-forties. Other than temporary layoffs, it was the first time since 1972 that I had been without a regular paycheck. Ahead lay disaster—spun from the ever-complex machinations of race . . . On April 29 1992, as I left a late morning meeting at the Department of Cultural Affairs, the verdict by the Simi Valley jury in the Rodney King beating case was announced . . . By the time I arrived home the city was again in flames . . .

“The Riot Inside Me,” page 258

What does a poet do when poetry is the most under-appreciated art in the nation—even considered subversive . . . Being who I am, I can’t not make note of the ironies—of the arrogance governing our nation’s rhetoric . . . I decided I had to get out of the house and drive out to the cemetery. I had not visited my father’s grave in over a year. I did as usual: took grass clippers, a rag, and bottled water, got down on my knees and tidied up, asking as I always do, the unanswerable.