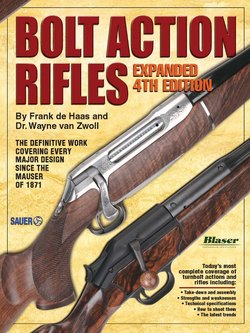

Читать книгу Bolt Action Rifles - Wayne Zwoll - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLee-Enfield Rifles FdH

British SMLE Mark III rifle, which later became the No. 1 Mark III.

THE BRITISH LEE-Enfield rifle has a long and colorful history; one which includes two World Wars, many smaller wars and conflicts covering wide areas and many countries over the face of the earth. The “Lee” of Lee-Enfield is James Paris Lee, a Scottish-born American firearms designer who invented the Lee turnbolt magazine firearm in 1879. A book could be written about the life and work of this inventor; it would be an interesting challenge for some biographer. “Enfield” derives from the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock in England, a great arms manufacturing plant where, for many years, most military development work was done on arms later adopted by Great Britain.

Many articles have been written about Lee and his turnbolt rifle that was the forerunner of the British Lee-Enfield. The reader need only check the bibliography at the back of this book to find a few of the articles published in American Rifleman. In addition, there is an excellent book on Lee-Enfields—The Lee-Enfield Rifle, by Major E.G.B. Reynolds— must reading for anyone interested in these arms. Because of this wealth of background material, I won’t go deeply into the history and development of this famous military rifle. I will limit my main discussion to the two Lee-Enfield actions used during two World Wars: The No. 1 Mark III of WWI and the No. 4 Mark I of WWII.

A very brief historical outline of the Lee-Enfield, however, is in order. After Lee patented his vertical magazine turnbolt action in 1879, he was not immediately successful in getting the rifles made and sold. He tried to interest the U.S. Navy in the design, but it was not until the Remington Arms Co. of Ilion, New York, bought the manufacturing rights that the Lee rifle had any worthwhile backing. Known as the Remington-Lee rifle, a few were sold to the Navy for experimental purposes in 1881. Remington tried in vain to interest the U.S. Army in the same rifle. Meanwhile, Remington also tried to interest foreign countries in the new rifle (some samples were made for China and Japan, among others) and did sell some to Cuba and Spain. At about this time (1883), England became interested in adopting a magazine rifle, and the Lee rifles submitted came out Lee-Enfield best in their 1887 trials. This brought Lee his first real taste of fame. The Remington firm then began making Remington-Lee sporting rifles for a variety of cartridges, eventually including the 6mm Lee, 30-30, 30-40, 303 British, 35 Remington, 45-70 and others. Remington made these rifles until about 1906.

After England’s initial acceptance, the Lee system was somewhat modified with development and manufacturing done at Enfield. The first British Lee rifle was the Lee-Metford Magazine Rifle Mark I, the design sealed in December, 1888. Various improvements and modifications followed with the first true Lee-Enfield being introduced late in 1895.*

This was followed by other changes, modifications and mark designations every few years or so until the Mark III was adopted in 1916 as the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE) No. 1 Mark III.

The Rifles

The No. 5 Mark I carbine weighs about 8.9 pounds, has a 25.2” barrel and is 44.8” overall. It has a full length forend, and the rear sight is mounted on the barrel.

The No. 4 Mark I rifle, about 8.6 pounds, has a 25.2” barrel and is 44.4” overall. Its forend extends nearly to the muzzle, and the rear sight is mounted on the receiver bridge. It was adopted in 1941.

The No. 5 Mark I carbine weighs about 7.2 pounds, has a 20.5” barrel and is 39.1” overall. Often called the “Jungle Carbine,” it has a short sporter-type forend and a funnel-like flash hider on the muzzle, but is otherwise like the No. 4 rifle. It was introduced in 1944. All Lee-Enfields were discontinued in 1954.

The No. 1 Mk. III Action

The Lee-Enfield receiver (called the “body” in England) is a one-piece steel forging which required a great many machine operations before it was finished. It is more complex than the usual centerfire turnbolt action because of the two-piece stock design; the separate buttstock is attached to the rear of the receiver (called the “butt socket”) by a through-bolt. The receiver forging was made with a large mass of metal on its rear which was milled and threaded to accept the buttstock tenon and the through-bolt. This is a very secure and rugged stock fastening.

The front end of the receiver has right-hand threads of the common V-type. A heavy collar is left inside the rear of the receiver ring against which the flat breech end of the barrel butts. The barrel is also made with a reinforced shoulder which butts against the front of the receiver, making a rigid barrel-to-receiver joint. A slot cut through the right side of the collar (and a matching beveled notch in the breech face of the barrel) admits the extractor hook. The collar closely surrounds the front of the bolt head and provides a good seal at the breech. Neither the face of the barrel (chamber) nor the bolt head is recessed for the cartridge head. Since the cartridge rim is nearly the same diameter as the bolt head, the head is so well sealed that a recess is not needed.

The center of the receiver is bored and milled to accept the two-piece bolt. The receiver bridge is slotted to allow passage of the right locking lug/guide rib and the extractor lug on the bolt head.

The heavy left wall of the receiver is slightly lower than the top of the receiver ring line. A shallow thumb notch is cut into it to aid in loading the rifle from the top through the opened action. The right wall is milled much lower than the left, providing ample opening for loading and ejection.

The receiver bridge is slotted through. It is, however, bridged over by the narrow clip-charger guide bridge over the middle of the receiver, connecting the high left wall with the low right wall. It appears that this clip-charger bridge was made from a separate piece of metal, then afterward forged to become integral with the receiver. The top front of this bridge is grooved to accept the 303 British stripper clip.

The two-piece bolt has a separate bolt head threaded into the front of the bolt body. The small hooked extractor fits in a slot through a lug on the bolt head, and is held in place by, and pivots on, a screw through the underside of the lug. A small but sturdy flat V-spring tensions the extractor. The extractor easily snaps over the rim of a cartridge placed in the chamber.

The bolt has dual-opposed locking lugs located slightly to the rear of its center. The left (bottom) locking lug engages in a recess milled into the left wall of the receiver bridge. The long guide rib on the right (top) of the bolt is also the right locking lug—it engages forward of the receiver bridge wall, on the right. Both lugs are solid, and the rear locking surface of each is slightly angled to cam the bolt forward as it rotates to the fully locked position. In addition, the front surface of the left lug is also angled to match the surface in its locking recess. This provides the initial extraction power when the bolt handle is raised. The bolt handle, at the extreme rear end of the bolt, has a tapered square-to-round stem that ends in a round grasping ball. When the bolt is closed and locked, the bolt handle lies against the butt socket of the receiver, with the grasping ball only slightly away from the side of the rifle. There is no auxiliary locking lug on the bolt.

The bolt head does not turn with the bolt. As the bolt is fully closed, the threads of the bolt head draw it against the front of the bolt—so the thrust of firing is not placed on the threads. The large lug on the bolt head housing the extractor also acts as the bolt-stop when it contacts the receiver bridge wall as the bolt is opened. A lip under the outside edge of the extractor lug fits over a groove cut into the top edge of the right receiver wall, and this keeps the bolt head from turning as the bolt is operated. This groove ends short of the receiver bridge wall. When the bolt is fully open, the extractor lug can be pulled up and rotated into a slot in the receiver bridge— the bolt can then be removed. A small spring retainer, provided in the right side of the receiver extractor-lug groove, engages with the lip under the extractor lug when the bolt is fully drawn back. It prevents the bolt head from turning under normal operation of the bolt, yet allows the bolt head to be rotated manually to remove the bolt from the action.

The firing mechanism consists of a one-piece firing pin, coil mainspring and cocking piece. The bolt is drilled from the front, with the mainspring compressed between a collar on the front of the firing pin and a rear shoulder in the bolt body. The rear end of the firing pin is threaded into the cocking piece. A screw at the rear of the cocking piece prevents the firing pin from turning. Forward travel of the firing pin is stopped when the collar on the firing pin contacts the back of the bolt head, not by the cocking piece contacting the rear of the bolt.

An arm or tongue on the bottom of the cocking piece extends forward under the bolt body, into a raceway milled in the receiver, where it engages the sear and safety projecting into this raceway. The action cocks on closing the bolt, the sear engaging the front of the cocking piece arm and holding it back as the bolt is closed. The head of the cocking piece may be round and knurled, or flat and notched. There is also a half-cock notch (called “half-bent” notch in England) on the arm of the cocking piece; by firmly grasping the cocking piece, it can be lowered from the cocked position or drawn back from the fired position to engage the sear in this intermediate position. This locks the bolt and the sear. To fire the rifle in this half-cock position, the cocking piece must be manually pulled back to full cock. Originally designed as a safety measure, the half-cock notch serves no useful purpose. There is also a small stud or cam on top of the cocking piece arm which engages a notch cut in the rear of the bolt body. On raising the bolt handle with the action closed and the striker down, the notch engages the stud and pushes the cocking piece and firing pin back. The purpose of this arrangement is to prevent the firing pin from going fully forward unless the bolt is locked. In other words, the Lee-Enfield action cannot be fired unless the bolt handle is nearly all the way down and the action locked.

No. 1 Mark III action.

The safety is at the left rear side of the receiver. A flattened integral stud on the safety projects into the cocking piece raceway. Two shallow notches cut into the left bottom edge of the cocking piece arm can engage the safety when it is swung back. These notches are so spaced that one or the other is opposite the safety when the rifle is cocked or uncocked. When the action is cocked, the safety locks both the striker and bolt; when uncocked, it locks the bolt and pulls the firing-pin tip within the bolt head so that a blow on the cocking piece cannot discharge the rifle.

The bolt is locked by a small part threaded on the stem of the safety. The thread is multithreaded and left hand. Part of this bolt lock extends through the receiver wall to engage in a groove cut into the rear of the bolt body. As the safety is swung back, the threads force the bolt lock toward the right to engage a groove in the bolt and lock it. A spring bracket screwed to the receiver holds the safety in place. (In England and perhaps elsewhere, the part which I call the “safety”—the part which actually locks the striker—is called the “locking bolt,” and the part I call the “bolt lock,” which actually locks the bolt, is called the “safety catch.”)

Left-side view of the No. 1 Mark III Lee-Enfield action.

Top view of the No. 1 Mark III action showing cutoff pulled out; the bolt will pick up cartridges from the magazine as the bolt is operated.

The sear, an L-shaped piece of metal, is held in place by, and pivots on, a screw under the receiver. This screw also holds the bolt-head release spring. It is under tension from a flat V-spring positioned between the sear and magazine catch which also supplies tension to these parts. The trigger pivots on a pin in the trigger guard. The curved trigger is grooved; its top part, which contacts the sear, has two bumps which provide the common double-stage military pull.

The detachable staggered-column box magazine, of ten-round capacity, is made from heavy-gauge sheet metal. The follower has a raised rib on its left side which causes the cartridges to lie staggered in the magazine. The follower is tensioned by a W-shaped spring. Curved lips at the front and rear of the magazine opening hold the cartridges in the magazine.

The magazine box, positioned in the milled-out bottom of the receiver by the trigger guard/magazine plate, is held up by the magazine latch. Partial cartridge guide lips, milled into both sides of the magazine well, hold and guide the cartridges into the chamber as they are fed out of the magazine by the bolt. The magazine can be single loaded whether in or out of the rifle, or it can be loaded with a stripper clip while in the rifle.

The No. 1 SMLE action has a cartridge cutoff, a flat triangular piece of metal positioned in a slot milled in the right receiver wall. It pivots on a screw through the bottom front edge of the receiver. Pushed in (engaged), the cutoff slides over the cartridges in the magazine, so the bolt can be closed without picking up a cartridge. This allows single-round loading, holding the cartridges in the magazine in reserve. Pulled out, the cutoff is inoperative, letting the bolt pick up the topmost cartridge in the magazine as it is closed.

The ejector is merely a small stud screw threaded into the left receiver wall. When the bolt is opened, the extracted case or cartridge slides along the inside wall of the receiver until its head strikes the end of the ejector screw—the bolt nearly all the way open. This tips the case to the right, out of the action.

A gas-escape hole in the bolt head vents any powder gases which might enter the firing-pin hole in the case of a pierced primer. It vents the gases upward along the edge of the left receiver wall. There is another small oblong gas-escape hole in the left side of the receiver ring, in line with the space occupied by the cartridge rim between the face of the bolt and barrel. There is also a notch cut into the rear of the receiver ring, just ahead of the extractor lug on the bolt head; this space, and the oblong hole opposite it, should expel any gases escaping from a ruptured case head.

A new system of model designation was introduced in May, 1926. The SMLE Mark III became the No. 1 Rifle, Mark III. The Pattern 1914 Rifle (known in the U.S. as the 1917 Enfield) became the No. 3 Rifle. The No. 4 Rifle, Mark I, was a development of the SMLE Mark VI.

The No. 1 Lee-Enfield (also known as the SMLE, for Short Magazine Lee-Enfield), introduced shortly after 1900, underwent many changes before the No. 4 Lee-Enfields were introduced about 1939. We are not concerned here with the many minor changes in the action, since it remained structurally the same. Officially, as each change was adopted, the model designation was changed, beginning with Mark I and continuing to Mark VI and including such asterisk or “starred” (*) designations as the Mark I*, etc., etc. The No. 1 action itself remained substantially the same for over 30 years, and since it was made in large quantities, it is the most common one.

The No. 4 Lee-Enfield Action

Little development was done on the Lee-Enfield rifle after WWI since the rifle and action had proved reliable during that conflict. Nor was there much need to make many additional rifles—at least not until WWII loomed into sight. However, it had been previously found that the rifle could be simplified and improved, and the action made somewhat stronger. The development work done accordingly was toward making the rifle more accurate, simpler and stronger. For example, it was found that the rifle gave better accuracy with an aperture sight mounted on the receiver and that there was no real need for the magazine cutoff. Thus, in the late 1930s, when the British again needed rifles, they adopted the Mark VI, a simplified and improved version that became the No. 4 Lee-Enfield.

Here are some of the changes adopted:

1) The cutoff was eliminated, the machining for it omitted. This left the right receiver wall stronger than before, simplified and stiffened the action, and left more metal in the right wall to support the right locking lug.

2) The bridge was made a bit higher so that a leaf aperture sight could be mounted.

3) The front of the bridge was also made a bit higher, so that a connecting strip of metal joining these projections formed a much smaller and neater clip-charger guide bridge.

Top view of the No. 1 Mark III Lee-Enfield action. Magazine cutoff is shown depressed.

No. 1 Mark III Lee-Enfield action, open, shown with stock bolt.

4) The thumb notch in the left receiver wall was made shallower, further strengthening the receiver.

5) The bolt head was altered, as well as the method by which it was guided and retained. The extractor lug was made smaller, and instead of engaging over the edge of the right receiver wall, it moved in a groove cut inside the wall. On early No. 4 actions, a plunger-type bolt head release, fitting in a mortise cut into the receiver, could be depressed to release the bolt head. Later, this release was omitted; instead, a notch cut out of the bolt head groove in the front of the right receiver wall allowed the bolt head to be rotated at this point for removal of the bolt from the action. With this change, the rifle became the No. 4 Mark 1*.

6) The safety shape was changed and a new safety spring used, eliminating the safety washer.

7) The left side of the bolt head was made flat to allow a greater amount of powder gases to escape out of the bolt head hole and past the receiver wall. The gas-escape hole in the left of the receiver was enlarged and made round.

In addition to the above, a groove was milled in the right locking lug/guide rib to make the bolt lighter. There are a number of changes in the configuration of the receiver which were the result of eliminating or simplifying the machining operations:

On late No. 4s, the trigger was pivoted in the receiver instead of in the trigger guard. The No. 4 actions in which the trigger was pivoted in a bracket brazed on to the butt socket became the Mark ½. Later, when the brazed-on bracket was eliminated and the trigger pivoted directly to the butt socket, the designation was changed to Mark 1/3.

The No. 5 Lee-Enfield Jungle Carbine has the same action as the No. 4.

Takedown and Assembly

Make certain the rifle is unloaded. Remove the magazine by lifting up the magazine latch in the trigger guard and pulling it out of the action.

Disassemble the magazine by depressing the rear of the follower until its front end slips out of the magazine box, then gently lift out the follower and follower spring. Reassemble in reverse order.

Remove the bolt from the No. 1 Mark III by raising the bolt handle and pulling the bolt back as far as it will go; then rotate the bolt head by lifting up on the extractor lug, and the bolt can be pulled from the action. To remove the bolt from the early No. 4 rifle, first tip up the rear sight, depress the bolt head release and open the bolt as far as it will go; now rotate the bolt head counterclockwise and pull the bolt from the receiver. On the late No. 4, open the bolt and pull it back about ½”, or until the bolt head can be rotated, then pull the bolt from the receiver.

To disassemble the bolt, unscrew the bolt head, remove the extractor screw, then pull out the extractor spring. Turn out the firing-pin lock screw from the cocking piece. Using the special tool shown, insert it into the front of the bolt and, while pressing the firing pin down with this tool, unscrew the firing pin from cocking piece. Reassemble in reverse order.

Remove the safety mechanism by turning out the safety-spring screw and lifting the safety-spring and safety parts from the receiver. If the bolt lock is removed from the safety, it must be re-aligned on the threads so that it will fit the hole in the receiver with the safety in the forward (FIRE) position.

Remove the buttstock by opening the buttplate trap and removing the felt wad that covers the stock bolt head; use a large, long-bladed screwdriver to unscrew the stock bolt. Remove the trigger guard/magazine plate by removing the rear and front trigger-guard screws, then lift it out of the forend. Remove the muzzle cap and barrel bands, then gently pull the forend away from the barrel and action.

On the No. 1 Mark III, turn out the magazine cutoff screw and remove the cutoff. Drive out the magazine-catch pin and remove the catch and spring. Turn out the bolt-head release-spring screw and remove the release spring and sear. Reassemble in reverse order.

On the No. 4, turn out the magazine-catch screw and remove the bolt-head release stop, bolt-head release, bolt-head release spring, magazine catch and spring. Drive out the sear pin and remove the sear. Drive out the trigger pin and remove the trigger. Reassemble in reverse order.

Markings

The No. 1 Mark III & III*: After assembly, each rifle was proved by firing two proof loads; these developed about 25 percent more breech pressure than the normal load. After inspection, if nothing was wrong with the rifle, British proof marks were stamped on the breech end of the barrel, receiver ring, bolt head and bolt body. The serial number was usually stamped on the barrel breech, receiver and stem of the bolt handle. The rest of the markings, stamped on the right side of the butt socket, include a proof mark, manufacturer, date and model designation as follows: A crown with the letters G.R. was stamped on top. Below this, the name or initials of the manufacturer was stamped; such as ENFIELD (for the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock, Middlesex, England), B.S.A.Co. (Birmingham Small Arms Co., Birmingham, England) or L.S.A.Co. (London Small Arms Co., of London); below this and over the model designation would be the date (year) the rifle was made, as follows:

British Lee-Enfield No. 5 Mark I Jungle Carbine.

SHTL.E.

III (or III*)

The letters “SHTL.E.” mean “Short Lee-Enfield.” The No. 1 rifles made in India were stamped ISHAPORE, those made in Australia were stamped LITHGOW, both cities in those countries. Various rifle parts also are stamped with inspector’s or viewer’s marks, which may be a number, a letter or both, often with a crown.

No. 4 Rifles were all made under more-or-less trying wartime conditions in a number of factories in England, the United States and Canada. The marking systems were so many and varied, and I can’t list them all. To begin with, most No. 4s were proof marked, serial numbered and dated, generally marked with the model designation and the name and/or place of manufacture.

Proof marks were usually stamped on the barrel breech, receiver ring, bolt head and bolt body. Serial number and date (year) of manufacture were usually stamped on the left side of the butt socket.

The model designation, was usually stamped on the left side of the receiver, as follows: N° 4 MK I, N° 4 MK I*, N° 4 MK ½, or N° 4 MK 1/3. If there is a “( T )” after the mark designation, this indicates the sniper rifle. The No. 5 Carbines are marked “No. 5”, followed by the mark designation.

Three firms in England made the No. 4 rifles. These firms were assigned blocks of serial numbers so that no two rifles would have the same number. The number was stamped (or sometimes etched) on the left side of the butt socket. Rifles marked with an FY or ROF(F) were from the Royal Ordnance Factory at Fazakerley, Lancashire, while those with an M, RM or ROF(M) came from the Royal Ordnance Factory at Maltby, Yorkshire. Those marked B, 85B or M 47 are from a BSA-controlled company in Shirley, near Birmingham. The word ENGLAND is often stamped on the receiver ring of these rifles.

The No. 4 Mark I* rifles made in the Long Branch arsenal near Toronto, Canada, were marked LONG BRANCH on the left side of the receiver. Rifles made in the U.S. by the Savage Arms Company (in the former J. Stevens Arms Co. plant in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts) were stamped U.S.PROPERTY on the left side of the receiver. (They were made under the Lend-Lease arrangement between the U.S. and England.) The serial number of these U.S.-made rifles includes the letter C, for Chicopee Falls.

Production

A great many Lee-Enfield rifles were made. Hundreds of thousands of the No.1 rifles were made at Enfield Lock, the factory that did most of the original development work on them. Over 2,000,000 were made at Enfield between August, 1914, and November, 1918. The large Birmingham Small Arms firm began making Lee-Enfields about 1903. During WWI, they made some 7000 to 10,000 a week, and during WWII they made about 1,250,000 of the No. 4 rifles. The factories in Australia made over 640,000 Lee-Enfields. Over 1,000,000 No. 4 rifles, including about 1000 sniper rifles, were made in the Long Branch arsenal in Canada. More than a million of the No. 4s were also made by Savage in the United States. This accounts for around 6,000,000 rifles, but that’s only part of the total production. I have no additional production figures, nor serial number records, so I can’t even guess how many were made in all. Nor do I have any figures on how many were imported into the U.S. as surplus arms after WWII, but it probably runs into hundreds of thousands. At least there are enough of them in the United States and the rest of the world to last a long time.