Читать книгу Impostures - al-Ḥarīrī - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Author’s Introduction

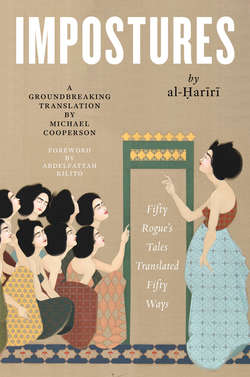

ОглавлениеIn this short Introduction, al-Ḥarīrī confides to God his fear of being so carried away by his own rhetoric that he strays from the truth. He claims to have written the Impostures under duress, though his protests are not very convincing. He also insists that his efforts, painstaking though they are, can only be an echo of the original Impostures, those of al-Hamadhānī. Finally, he defends the practice of inventing characters and speeches in order to make a point. To convey a sense of the balanced, rhythmic character of al-Ḥarīrī’s Arabic, the English Introduction imitates the style of Edward Gibbon (d. 1794), whose Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire uses a variety of rhetorical devices to achieve a stately momentum.

0.1In the name of the most merciful God

Lord, let my gratitude to thee insure the renewal of thy bounty.

Thou hast imparted to us the art of declamation, and instilled in us the power of discernment. Grateful for thy gifts, and safe beneath thy shield, I offer thee the tribute of thanksgiving. From intemperance, as from bombast, guard my tongue; let no defect in speech, or sudden fit of stammering, make me ridiculous. May flattery not inspire, nor indulgence nourish, an unbecoming pride. Be thou my bulwark against hostile and contumacious spirits! Forgive me for kindling those passions that lead, by insensible degrees, to profligacy and vice; and for directing the reader’s steps toward the precipice of sin. Bestow, rather, maturity of judgment, and a disposition to yield to the just demands of truth. Suffer me to speak with an honest voice. Let a firm resolve check the arrogance, and temper the excesses, of self-love. Guide me gently to a more perfect understanding, supply my want of eloquence, and defend me from error in the quoting of authorities. Curb my levity, lest it assume the character of insolence. Suffer me not to reap the bitter harvest of loquacity, or yield to the blandishments of pomposity and affectation. Let me have no reason to feel the lashings of remorse; let me furnish no pretext for censure or reproach; and let me not excite, by some thoughtless ejaculation, the reader’s just reproof.

0.2Admit, Lord, my petition; grant my wish; admit me to thy sanctuary; suffer me not to be consumed. In fervent supplication, I implore thy boundless mercy. If humility avails, behold my abject plea; if an offering must be made, I have nothing to offer but hope. I entreat thee also in the name of Mahomet, our lord and intercessor, the seal of the prophets, whom thou hast raised to the loftiest heights of heaven, and exempted from the penalty of sin. Of him a passage of the Koran, the most credible of witnesses, declares: “These are the words of an honourable messenger, endued with strength, of established dignity in the sight of the possessor of the throne, obeyed and faithful.” Lord, bless the Prophet and those trusted guides, his kinsmen, as well as his companions, who raised and preserved the edifice of his faith. Make us worthy of their guiding hand, and deserving of their tender care.

0.3In a certain assembly, convened to promote a learning now sunk in oblivion, mention was made of the Impostures devised, with much ingenuity, by the Wonder of the Age, Badee al-Zamán, the prodigy of Ecbatana; and ascribed by him to Abu Al-Fath of Scanderoon, and Jesu ben Hesham. The former is said to be the author, the latter the chronicler, of those harangues. Both, however, are buried in obscurity, and must defy every attempt to determine their identities. At the mention of Badee’s Impostures, a certain personage, whose command is no less profitably than deservedly obeyed, enjoined me to compose an imitation of them, even though it be a faint and feeble copy. I reminded him, with copious proofs, of the harsh treatment sustained by authors, whether of prose or verse. I begged him to release me from a trial as bewildering to the understanding, as merciless in its demands upon the powers of invention; one as likely to expose a man’s ignorance, as to display his worth. Any one so engaged (I said), gathers wood by night, or levies foot and horse: I mean, undertakes a work, where mere industry cannot prevent, and indeed must promote, the accumulation of useless matter.

0.4It was in vain that I begged to be released from the duty of obedience. I resolved, therefore, to acquit myself of the charge with all the diligence I could muster. Though wanting in ingenuity, impoverished in invention, and distracted by painful cares, I composed, after a long struggle, these fifty Impostures. In them are mixed the grave and the ridiculous, the rugged and the delicate. Studded with the gems of oratory, salted with the table-talk of cultivated men, and emblazoned with verses of the Koran, they are replete with figures and allegories, proverbs and maxims, literary subtleties and grammatical enigmas, and judgments on disputed points of speech. Nor will they be found deficient in pleasantry and laughter, in epistles ingenuously contrived, in orations gaudily bedecked, or in sermons bedewed with the tears of penitence. All these are placed in the mouth of Abu Zeid of Batnae, as if related to me by Hareth Ebn Hamam of Bassora. Thus urged from one pasture to another, my readers will, I trust, peruse with eager curiosity the lessons they encounter. With regard to poetry, almost all the verses are my own. The exceptions are the two upon which the second Imposture, “A Basran Boswell,” is based; and the distich comprised in the twenty-fifth, “De froid trempé.” The rest are my virgin-brides: the luscious fruit, or bitter weeds, of my invention.

0.5Yet so far has Badee, the prodigy of Ecbatana, outstripped every courser in the race, that all who vie with him in the making of Impostures, be they granted the eloquence of Kodama, tread a path well-trod, and quaff a cup already drained. A poet says:

Had I wept first, instead of bitter grief

I might ere now have tasted sweet relief;

But wept I not, till I beheld her sighs;

So precedence is hers, and hers the prize.

0.6It is my hope, that having presumed to lay this work of turgid rhetoric before the public, I may yet escape the blame naturally incurred by any who hands his executioner the knife; or amputates, with more severity than sense, his own offending nose. “Shall we declare unto you,” says the Koran, “those whose works are vain, whose endeavor in the present life hath been wrongly directed, and who think they do the work which is right?” Though partiality be disposed to overlook, and friendship to excuse, the manifest deficiencies of this book, it is unlikely to escape the cavils of the ignorant, or the calumny of the wilful. This fiction, its captious judge will say, violates the laws of God. Yet the eye of reason, that sees by the light of first principles, will find it a work of instruction, similar to those fables told of talking animals, or mute objects brought to life. Is there one who refuses to listen to such tales, or condemns their recital, in an idle hour? If our deeds are judged, as our acts of worship are affirmed, by our intentions, how can justice reprove any one who composes pleasantries, not to deceive, but to teach; and whose fables pretend to utility, not veracity, in the correction of error? I know not how such an author differs from any teacher of virtue or religion.

Do not resist the Muse’s mighty gale:

Against her force no mortal can prevail.

When she slackens, thou mayest slip away:

Do but survive, and thou hast won the day.

In this as in all my designs, I grasp the strong arm of God, that he might conduct me in the right path, and steer me past the stumbling-block. He is my succor and my sanctuary, my refuge and my guide. Upon him I rely, and to him I turn in penitence.