Читать книгу Impostures - al-Ḥarīrī - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

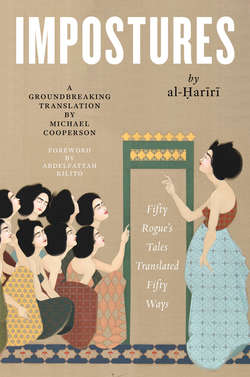

ОглавлениеIn 382/992, in the city of Nishapur in the northeast corner of what is now Iran, a young visitor named al-Hamadhānī astounded the city’s elite by defeating a local celebrity in a prose-and-poetry slam. 2 At various points during the contest, al-Hamadhānī offered to produce pieces of language subject to odd constraints: an essay without the word “the” in it, for example, or one containing verses embedded in it diagonally. Dismissing such games as “verbal jugglery,” his opponent demanded that he improvise a bureaucratic letter on a topic suggested by the audience. Al-Hamadhānī accepted this conventional challenge but added a twist that let him show off his talent: he improvised his letter starting from the last word and working backward.

Al-Hamadhānī, called “The Wonder of the Age,” died young. His greatest work, at least in retrospect, 3 is a collection of unusual stories called maqāmāt, a term I translate (following a suggestion by Shawkat Toorawa) as “impostures.” 4 Although al-Hamadhānī’s fifty-odd Impostures differ widely in content, certain characters and themes recur. 5 Every Imposture has a narrator who travels from one city or region to another. Everywhere he goes, he encounters an enigmatic figure endowed with stunning eloquence. In some cases, this figure shows off his wit at a gathering of scholars. In others he is found begging in a market or a mosque. Some Impostures contain little more than speeches and verses, but others go on to tell a story that exposes the eloquent preacher as a sinner and a fraud. 6

Although the so-called picaresque Impostures (that is, the ones with stories) have attracted the most attention in modern times, pre-modern Arabic readers were more interested in the verbal performances. Indeed, the Imposture’s most striking feature is its form. Whether spoken by the narrator, the eloquent stranger, or one of the occasional characters, the frame story and the speeches are almost all in rhymed prose. The speeches are punctuated by verse, which unlike the prose has a single rhyme and a consistent number of feet per line. Strikingly, none of al-Hamadhānī’s Impostures are palindromic, lipogrammatic, or otherwise constrained, even though al-Hamadhānī claimed he could produce texts that were. 7 But even without those flourishes, his work was regarded as the freakish production of a boy genius unlikely to be imitated, let alone outdone.

So matters stood until 495/1101–2, 8 when an unlikely prospect named al-Ḥarīrī 9 decided to challenge the Wonder of the Age. 10 Al-Ḥarīrī (who was born in 446/1054 and died in 516/1122) 11 was a proud citizen of the southern Iraqi town of Basra. During his lifetime, the town was governed by a motley parade of Abbasid caliphs, Seljuk sultans, Arab chieftains, and Turkish emirs. 12 One source reports that al-Ḥarīrī was a wealthy landowner while another claims he was employed by the Abbasid administration in Baghdad to report on local affairs. Though “extremely clever and articulate,” he was also “short, ugly, stingy, and filthy in his person” 13—all liabilities in a world where knowledge was transmitted face to face and being an author often meant performing one’s works in public. Most damningly, al-Ḥarīrī was unable to compose on the spot. While thinking, he would pull at his beard, which he did so often that he plucked the hairs out. 14 After he presented his first Imposture he was asked to write another, but even after weeks of solitary effort, “blackening page after page,” he “found himself unable to put two words together.” 15 Later, after he had managed to produce forty episodes, he was asked, while calling on a high official in Baghdad, to improvise one more. “Taking pen case and paper, he went off to a corner of the audience room and remained there for a good long while, but no inspiration came and he left the room, mortified.” 16 So unlikely a superstar did he seem that he was widely accused of plagiarizing his stories from a visiting North African.

But al-Ḥarīrī had the last laugh. When the Impostures were finished, he took his scribbled manuscript to Baghdad. There he read the work aloud to one al-Mubārak al-Anṣārī, who made a fair copy. In Rajab 504/January 1111, al-Ḥarīrī invited a group of prominent literary and legal scholars to hear the first five Impostures read aloud. The attendees must have liked what they heard, as many of them returned for session after session to hear the whole work through. Just over a month later, on Shaʿban 7, 504/February 18, 1111, the first public reading of the Impostures came to an end, with at least thirty-eight senior men of letters in attendance. The auditors’ names and the precise date of the last session are carefully noted on al-Mubārak’s fair copy, which by some miracle has survived into modern times.

After the first reading of the Impostures was finished, the fair copy was used to teach the Impostures another twenty-nine times. The last of these teach-ins took place in Damascus in Rabiʿ al-Awwal 683/June 1284. 17 As impressive as its diffusion is, this manuscript is only one of the seven hundred copies reportedly approved by al-Ḥarīrī himself. This number means that he was approached seven hundred times by people who wanted him to confirm that they had studied an authentic copy of his work. 18 After his death, the Impostures continued to grow in popularity. As one of his biographers puts it:

The Impostures have enjoyed a reception unlike anything else in literary history. The work is of such a high standard, so marvelous in expression, and so copious in vocabulary, as to carry all before it. The author’s choice of words, and his careful arrangement of them, are such that one might well despair of imitating him, much less of matching his achievement. The work is justly celebrated by critics as well as admirers, and has received more than its due of accolades. 19

Unlike al-Hamadhānī’s, al-Ḥarīrī’s Impostures are clearly intended to fit together as a collection. In the first Imposture, the narrator, al-Ḥārith, meets the eloquent rogue, Abū Zayd, for the first time; in the last Imposture, Abū Zayd supposedly reforms. There is also more consistency across the stories. With a few notable exceptions, all of them feature Abū Zayd as “a clever and unscrupulous protagonist, disguised differently in each episode,” who “succeeds, through a display of eloquence, in swindling money out of the gullible narrator”—namely, al-Ḥārith, “who only realizes [Abū Zayd’s] identity . . . when it is too late.” 20 In effect, al-Ḥarīrī has taken one of al-Hamadhānī’s plots and standardized it. He is also more consistent than his predecessor in matters of form. Al-Hamadhānī may have one poem in an Imposture, or several, or none, while al-Ḥarīrī often has just two. Similarly, al-Hamadhānī frequently drops out of rhyme in transitional passages, while al-Ḥarīrī almost never drops out of rhyme unless he is quoting a Qurʾanic verse or pious formula.

Most famously, al-Ḥarīrī made a point of including examples of the kinds of trick writing that his predecessor had claimed to be able to produce. In Imposture 28, the roguish Abū Zayd delivers a sermon in which every word consists entirely of undotted letters (excluding, that is, half the letters in the Arabic alphabet). In Imposture 6, he dictates a letter in which every second word contains only dotted letters and the remaining words only undotted ones. In Impostures 8, 35, 43, and 44, he composes a story or poem that seems to be about one thing but contains so many words with double meanings that it can be read as telling an equally coherent story about something else. In Imposture 16, he extemporizes several palindromes (sentences that read the same backward as forward). In Imposture 17, he delivers a sermon that can be read word by word from the end to produce a different but equally plausible speech. In 32, he produces ninety legal riddles, each based on a pun. And in 46, he trains schoolchildren to perform feats such as taking all the words that contain the rare letter ẓāʾ and putting them into a poem. To some critics, manipulations like these have seemed an embarrassing waste of time, and evidence of the decadence of “Oriental taste.” 21 To my mind, however, they lie at the heart of al-Ḥarīrī’s enterprise.

As Matthew Keegan has recently argued, the Impostures are about learning. 22 Here it is useful to recall that twelfth-century Arabic was not simply a means of communication in the ordinary sense. For one thing, native speakers had long been in the minority in the territories captured by Islam, and in many places still were. Thus it was by no means guaranteed that any given Muslim, much less anyone living under Muslim rule, could speak the language. Moreover, Arabic was the language in which God had revealed the Qurʾan to the Prophet Muḥammad. For non-native speakers, learning it meant fully inhabiting one’s identity as a Muslim—and not coincidentally making oneself eligible for opportunities denied to one’s monolingual Persian-, Coptic-, Berber-, or Aramaic-speaking cousins. This aspirational quality of Arabic is evident from the eagerness with which al-Ḥarīrī’s characters debate fine points of grammar, semantics, and etymology. It also explains their palpable fear of making mistakes, as well as their chagrin when Abū Zayd outdoes them in punning, rhyming, riddling, or whatever the challenge might be.

Yet Abū Zayd does more than take cocky neophytes down a peg. He does things with language that are practically impossible—at least, if one imagines him doing them on the spot. In imagining a character with such extraordinary powers, al-Ḥarīrī seems to be grappling with the problem of divine and human language. When God conveyed his final revelation to humankind, he did so in Arabic. With the end of revelation, Arabic becomes a merely human language once again. As such, it can be used to inform, guide, or illuminate, but it can also be used to lie, cheat, defraud, swindle, and deceive. Yet even when it is being used dishonestly, it retains its numinous character: that is, its memory of having once been the voice of the Eternal. 23 Like Milton’s Satan, it retains, even after its fall, some of its original God-given beauty:

. . . his form had not yet lost

All her Original brightness, nor appear’d

Less than Arch Angel ruind, and th’ excess

Of Glory obscur’d . . . 24

It is this numinous character of Arabic that makes verbal miracles possible. It allows Abū Zayd to compose sermons without dots, or verses full of ẓāʾ-words, or speeches that can be read both backward and forward. These are not idle tricks: as Katia Zakharia has argued, games played with a sacred language are never just games. 25 Rather, Abū Zayd’s performances convey what Stephen Greenblatt has called “a pervasive sense . . . that there is something uncanny about language, something that is not quite human.” 26

If we take this tack, a number of things make sense. The narrator, al-Ḥārith ibn Hammām, begins many of the routines by telling us that he went to one town or another in search of some inspiring oratory. This quest appears insufficiently motivated unless we read it as a thwarted reflex of a spiritual search. In late antique Egypt, Christians would journey into the desert in search of holy men, and when they found them, would say, “Give me a word,” meaning a memorable summation of some spiritual precept. 27 This is the sort of word al-Ḥārith is looking for, even if he calls it adab (an Arabic word meaning “disciplined self-presentation” as well as “literary and linguistic training”). 28 Naturally enough, he is drawn to the shabby, hermit-like figure he sees haranguing crowds all over the world. And indeed, Abū Zayd is always up to the task of saying whatever needs to be said as eloquently as possible. Otherwise, there is nothing definite or stable about him: he varies so much in appearance and demeanor that al-Ḥārith almost always fails to recognize him. Abū Zayd may be what Abdelfattah Kilito says he is: a sorcerer’s apprentice who loses control of the forces he has set in motion. 29 But the most economical explanation for his vaporous indeterminacy is that he is Arabic itself. To paraphrase Sheldon Pollock’s description of Sanskrit, he is the language of God in the world of men. 30 And that language is so powerfully in excess of material reality that it overwhelms the agreed-upon relationship of word and object. This unmooring of meaning creates what Daniel Beaumont, one of al-Ḥarīrī’s most perceptive readers, calls the work’s “dreamy, haunting mood.” 31 It also makes Abū Zayd’s manifestations of piety seem forced and unconvincing. By this I do not mean that the real Abū Zayd is a sinner or a hypocrite. As Beaumont reminds us, there is no real Abū Zayd, only “the materialization of a function.” 32 Rather, I mean that when language becomes unmoored from reality, it becomes unmoored from the sacred as well. Al-Ḥarīrī’s language is saturated with the Qurʾan, the Hadith (reports of the Prophet’s words and actions), the rhythms of ritual, and the vocabulary of the religious sciences. But that language is left to fend for itself in a world that seems largely hostile to its purposes, where “the truth is incessantly discovered to be a pack of lies.” 33 Of course, Abū Zayd prays to God to deliver him from poverty and exile, and see him safely to Sarūj, his lost hometown. But the entity that actually defines his life is chance, which is usually malign.

The result of Abū Zayd’s predicament is a desperate search for a passage through or around language. At least, this is one way to make sense of his trajectory. For his part, al-Ḥārith so craves spiritual experience that he is willing to scour the earth “from Ghana to Fergana” (§9.1) in search of words to help him find it. Strangely, though, none of Abū Zayd’s sermons move him to tears of penitence. What al-Ḥārith fails to understand is that the word is not God. His teacher’s speeches are about themselves; the divine must be approached by other means, if it is approachable at all. This is why, despite their humor and occasional raunchiness, the Impostures are suffused with a desperate sadness. 34 Language remains marvelous, but even as we marvel, we know we are seeing an imposture.