Читать книгу Impostures - al-Ḥarīrī - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

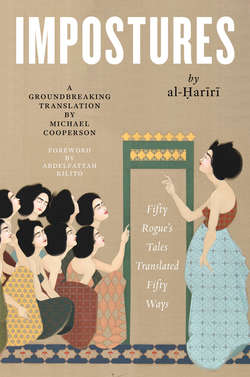

Note on the Translation

ОглавлениеIntroducing her successful translation of Homer’s Odyssey, Emily Wilson explains her choice of a low-key idiom:

Impressive displays of rhetoric and linguistic force are a good way to seem important and invite a particular kind of admiration, but they tend to silence dissent and discourage deeper modes of engagement. A consistently elevated style can make it harder for readers to keep track of what is at stake in the story. My translation is, I hope, recognizable as an epic poem, but it is one that avoids trumpeting its own status with bright, noisy linguistic fireworks, in order to invite a more thoughtful consideration of what the narrative means, and the ways it matters. 35

Without articulating the principle as clearly as Wilson has, I have always tried to translate in the self-effacing way she describes. But what is a translator to do with an original text whose avowed purpose is to fire off “bright, noisy linguistic fireworks”? Al-Ḥarīrī’s Impostures do not simply include some excessive verbal performances; excessive verbal performance is what they are about. It seems to me, therefore, that any translation that fails to reproduce this feature sells the original short. The problem, of course, is that so many of the fireworks are tied to particular features of Arabic. These include rhyme, especially prose rhyme, and constrained writing—lipograms, palindromes, and the like. Strictly speaking, none of these features can be translated; they can only be imitated. And the only way to imitate them is to throw out the rule book. To understand why, it will be helpful to look at how other translators have treated the Impostures.

In the pre-modern period, responses to al-Ḥarīrī included everything from annotations to word-for-word renditions to imitations to translations proper. The Persian-language responses, documented by ʿAlī Ravāqī, include four translations produced or copied between ad 1191 and 1809. 36 All of them are interlinear, meaning that Persian equivalents for the Arabic words are written between the lines of al-Ḥarīrī’s text. At least one of these translations can be read straight through—that is, it consists of continuous Persian text, not simply a sequence of word-for-word equivalents. Still, what it conveys is the referential or propositional content: in other words, what the text says but not what it does in terms of rhyme, constrained writing, and so on. Presumably, translations of this kind were made to help readers whose main interest was reading the Arabic.

Not all approaches were so timid. In 551/1156, Qāẓī Ḥamīd al-Din Balkhī, known as Ḥamīdī (d. 556/1164), discovered the Impostures, which he compares to “blazoned volumes” and “coffers full of precious stones.” But, he points out, they do not mean very much to speakers of Persian:

All their Wit avails the Gentile naught, nor do have the Persians any Share in those Rarities; any more than the Fables of Balkh should captivate the Ear, if recounted in the Patois of Karkh, or the Repartee of Rey retain its Charm, if rendered in Arabick, for lo:

Wouldst thou tell thy Sorrows to Men abroad?

In their Tongue, then, let thy Discourse be:

Bid the Arab ífʿal! or else lâ táfal!

But say kón, or mákon, to a good Parsee. 37

Using the simple example of imperative verbs (Do! Don’t!), Ḥamīdī suggests that transferring content between languages is a matter of finding the idiom that one’s audience understands. In his view, the best way to convey the experience of reading al-Hamadhānī and al-Ḥarīrī was not to translate but rather to compose original Impostures in Persian. Though they take the form of rhetorical displays rather than stories, Ḥamīdī’s Impostures are faithful to the form—that is, they combine verse and rhyming prose. And, in one way at least, he outdoes his predecessors: his Impostures mix Persian and Arabic. As eloquent as they may have been, al-Hamadhānī and al-Ḥarīrī worked their magic in only one language; Ḥamīdī works his in two.

A half century after Ḥamīdī, Yehudah ben Shlomo al-Ḥarīzī (d. 622/1225), a Jewish scholar living in Aleppo, took up the challenge of putting al-Ḥarīrī into Hebrew. 38 Writing after the fact, he describes the original Arabic Impostures as terrifying to all who heard them. No wonder, then, that those who first attempted to put them into Hebrew “captured rightly but one in fifty parts.” But the problem, it turns out, was not that it cannot be done. Rather, it was that the ones trying did not know Hebrew well enough: “The burning bush beckons—but they hear not; ears have they—but they hear not.” The citation of Exodus 3:1–5 makes the point that all the words a Hebrew translator needs are in the Bible; it is merely a matter of taking the trouble to look for them.

Al-Ḥarīzī clearly knew the Bible well enough: his translation, called Maḥberot Ithiʾel (“The Compositions of Ithiʾel”) is a masterpiece of ingenuity. Although the only surviving copy begins partway through the first and ends partway through the twenty-seventh Imposture, a later reference indicates that he translated all fifty. The same later reference explains why: to show that the “Holy Tongue” could do anything that Arabic could do. 39 This being his aim, the timid lexical approach was not an option. For the poetry, he produces poetry, and for the rhymed prose, rhymed prose. Moreover, he naturalizes the allusions, even to the point of Biblicizing the names. Abū Zayd, for example, becomes Ḥever, after “a charmer” mentioned in Psalms 58:6, with the tribal name ha-Qeni, after the Qenites, a tribe of wanderers who appear in Genesis 4:12 and Numbers 24:21–22. 40 Al-Ḥarīzī even manages to imitate most of the special effects, including, for example, the palindromes in Imposture 16. 41 In only a few cases does his ingenuity fail. Imposture 6 contains a passage in which half the words are entirely dotted and the other half undotted, in alternation. After breaking the fourth wall to explain the constraint, al-Ḥarīzī admits defeat: “We could not reproduce this particular feature in the Holy Tongue.” Instead he offers “a rendering of the sense.” 42

Both Ḥamīdī and al-Ḥarīzī display a healthy appreciation for al-Ḥarīrī’s “bright, noisy linguistic fireworks.” Strikingly, though, neither suggests that the Impostures are untranslatable. In his work on Arabic and Persian poetics, Alexander Key has proposed that untranslatability, as a presumed property of certain foreign texts, is a modern idea. For their part, pre-modern readers believed that content (maʿnā) was always transferable between languages. 43 Applied to Ḥamīdī and al-Ḥarīzī, at least, Key’s argument rings true. Of course, the assumption that anything could be translated did not make everything translatable: as we have seen, Ḥamīdī chose to imitate rather than translate, and al-Ḥarīzī had to let at least one of al-Ḥarīrī’s word games go unreplicated. Even so, the idea of intrinsic untranslatability—which is arguably the product of early-modern European notions about the spirit of peoples being embodied in their languages—does not apply, at least when it comes to human language.

It was only when al-Ḥarīrī arrived in Europe that he became untranslatable. But this verdict was not issued immediately. As recent work by Jan Loop has shown, early-modern European scholars hoped to find in the Impostures “an ideal text with which to practice and teach the Arabic language.” This they needed in order to pursue their broader aim, which was “to unlock the mysteries in the Hebrew texts of the Old Testament” and ultimately “to solve all theological questions.” 44 It was against this background that Jacobus Golius (d. 1667) produced a Latin rendering of Imposture 1 in 1656. 45 His work was “re-publiſhed with much larger notes, by that great Maſter of Arabic, Albert Schultens, at Franequer, 4to, 1731 [. . . to] which he added five more, purſuing the same method that he took in the firſt, of explaining difficult paſſages from the Scholiaſst, &c.” 46 The reference here is to the Dutch Orientalist Albert Schultens (d. 1750), whose edition and Latin translation of the first six Impostures formed the basis of the first English translation, that of Leonard Chappelow.

Chappelow’s rendition, published in 1767, offers a fascinating glimpse of a moment when the “ingenious conversations of Learned Men among the Arabians” could still be treated with reverence by English readers. Chappelow, who was a clergyman as well as the professor of Arabic at Cambridge, reads al-Ḥarīrī as “a prudent, diſcreet Satyriſt” who, had he been introduced to Christianity, “would have lived and died a Chriſtian in the beſt and trueſt senſe.” In keeping with his assumption that the Impostures should be scoured for lessons “inſtrumental in promoting the comfort and happineſs of life,” his translation of the first six Impostures operates on the principle of expansion. That is, every word is given as many of its senses as possible, and all are included in the same sentence, producing English that is a great deal longer than the Arabic it is supposed to be rendering. 47

In the writings of the splendidly named French Orientalist Jean Michel de Venture de Paradis (d. 1799) we find a reading of the Impostures that is much closer to our own. We also find an early expression of the belief that they cannot be translated. An Imposture (Mecamé), says Venture de Paradis, is the story of an amusing adventure told in elevated style. Because Impostures owe so much of their beauty to puns, rhymes, rare words, and far-fetched figures of speech, “it is very difficult, and often impossible, to render them in another language.” 48 His own timidly literal French translations make no attempt to render those features he acknowledged as indispensable to the appeal of the original. But at least he found them appealing; some of his successors would not.

In 1822 the great French Orientalist Silvestre de Sacy published what was to become the standard critical edition of al-Ḥarīrī’s Impostures. In his preface he addresses the question of why he did not translate the text into Latin or French. What matters about the Impostures (Séances), he says, is their form, not their content. Many episodes consist of “riddles, anagrams, and puns . . . that even the most gifted translator could not put into another language.” 49 Nor indeed should any translator want to: though the word games can be amusing, they can also be tiresome and pointless. 50 Clearly, we have come a long way from Chappelow and his belief that the Impostures are full of good advice for living a better life.

For de Sacy, the Impostures are most useful as a means to learn the fine points of Arabic. Even so, he admits that there is something irresistible about them. And he offers a perceptive diagnosis of why translations into European languages have failed to do them justice. Translators, he says, feel obligated to retain the allusions they find in the original. But then they must do one of two things, neither of which works. If they leave the allusions unexplained, the reader will have trouble understanding what is going on. But if the allusions are explained, they will draw more attention to themselves than they do in the original, spoiling the effect of al-Ḥarīrī’s style. 51

This insight was not wasted on the German Romantic poet Friedrich Rückert (d. 1866), the next great translator of the Impostures, and the first after al-Ḥarīzī to venture beyond plodding literalism. In the preface to his Verwandlungen des Abu Seid von Seruj, which appeared in 1826, Rückert admits that a translator who approaches the Impostures as a specifically Oriental text would indeed have to explain all the cultural references, since al-Ḥarīrī, unlike Homer or Shakespeare, is culturally alien to German readers. But Rückert refuses to produce an academic treatise. Instead, he says, he decided to focus on the poetic elements: the “incessant word- and sound-play, the rhymed prose, the over-the-top images, and the hairsplitting, overwrought expressions.” The result, he says, is not a translation but a recasting (Nachbilding) of the Impostures. 52

True to his word, Rückert strives to replace al-Ḥarīrī’s special effects with equally elaborate tricks in German. To translate the palindromes, for example, he uses Doppelreim, a form where the ultimate and the penultimate stressed syllables in each line rhyme with their respective counterparts in successive lines. 53 Yet even Rückert could not come up with an equivalent for everything. Like al-Ḥarīzī before him, he throws up his hands at the dotted and undotted epistle. The German text faithfully reports that the challenge is to avoid certain letters, but not which ones or why; and, as far as I can tell, the German epistle obeys no constraint. 54 In other cases, the difficulty proved so insuperable that entire episodes had to be dropped. And Imposture 20 he appears to have omitted simply because of its sexual content. As a result of these avoidances and omissions, his translation contains only forty-three Impostures.

With Rückert’s German on his desk, Theodore Preston, fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, produced the first English translation to acknowledge the formal properties of the Impostures. His 1850 rendering uses “a species of composition which occupies a middle place between prose and verse,” not rhyming, but “arranged as far as possible in evenly balanced periods.” But the more complex special effects—the puns, palindromes, and so forth—presented “almost insuperable obstacles,” leading him to omit three-fifths of the text. 55 And the copious notes betray his failure to heed Rückert’s warning that any translation that treats the Impostures as a text to be parsed for information about something else (the manners and customs of the Orient, for example) will produce an academic treatise rather than a work of art.

After Preston there was one more nineteenth-century attempt to put the Impostures into English. The initiative was that of Thomas Chenery, a Barbados-born polyglot who resigned from a position at Oxford to assume editorship of The Times of London. 56 Following de Sacy’s advice, he decided to treat the Impostures as a teaching text. 57 In 1866, he published a translation of the first twenty-six episodes, stating flatly that he had made “no attempt to imitate the plays on words, or the rhyme of the original” but rather composed “a literal prose rendering, intended primarily to help the student in Arabic.” 58 After Chenery’s untimely death in 1884, his work was carried on by the German-born Orientalist Francis Joseph Steingass, whose rendition of the remaining episodes appeared in 1898. In a preface, F. F. Arbuthnot tells us that Steingass “completed his portion of the work under great physical difficulties. . . . For some part of the time he was actually blind.” 59 Like his predecessor’s, Steingass’s rendering is strictly lexical. And, like Preston, both Chenery and Steingass append page after page of annotation, as if still laboring under the conviction that if the Impostures could not be translated they could at least be explained.

Whatever the merits of the lexical approach, it must be admitted that it has contributed nothing to making the Impostures part of Anglophone literary culture. Outside the narrow confines of medieval literary scholarship, I have never seen a reference in English to any of these translations, nor any other evidence that nonspecialists have heard of al-Ḥarīrī or, for that matter, of al-Hamadhānī (whose Impostures were translated, also lexically, by Prendergast in 1915), or of anything called a maqāmah.

In Russian, the situation is quite different: the Impostures exists as a full-fledged literary text. This is the result of work by Anna Arkadievna Iskoz-Dolinina (d. 2017) and Valentin Michaelovich Borisov (d. 1985), whose partial translation appeared in 1978, followed by a complete translation, with Valeria Kirpichenko (d. 2015), in 1987. 60 Like al-Ḥarīzī and Rückert, the translators render poetry as poetry and rhymed prose as rhymed prose. The latter, they say, can work in Russian, since Russian prose, like Arabic, can be made rhythmic by repeated sounds and parallel grammatical forms. Arguing, however, that too close an imitation of the Arabic form would result in unreadability, they unpack al-Ḥarīrī’s dense conceits and let his clauses go on longer than they do in Arabic before ending them with a rhyme word. 61 The result is a distinctively patterned yet still readable text—one that became a Russian bestseller and won, along with Dolinina’s translation of al-Hamadhānī, a major Saudi translation award in 2012. 62

As far as I know, the only other languages in which complete translations exist are Ottoman and modern Turkish, French, and Chinese. 63 The Ottoman translations include four complete and three partial renderings. Of these, the only one I have been able to look at is the partial translation published by Hâşim Veli in 1908 or 1909. It is intricately patterned, full of lightly rhythmical sentences and Arabic-style prose rhyme (Kaplan, “Roma Sefâreti Imami Hâşim Velî’nin Makâmât-i Harîrî Tercümesi,” 219–21). There is also a modern Turkish translation by Sabri Sevsevil (Kiliç, “Makamat”). The French translation, by René Khawam (d. 2004), appeared under the title Le Livre des malins (The Book of Rascals) in 1992. Like the English of Chenery and Steingass, it acknowledges the formal properties of al-Ḥarīrī’s work without actually trying to duplicate them. The prose is neither rhymed nor marked in any other way, and the verse is simply prose formatted as verse. Similarly, the special effects are noted but not imitated. In Imposture 16, for example, Khawam has al-Ḥārith explain the palindrome game (which he does incorrectly) but then translates all the Arabic palindromes literally into French, resulting, obviously, in phrases that are not reversible. 64 By contrast, the French translation of al-Hamadhānī’s Impostures, published by Philippe Vigreux in 2012, does a masterful job of reproducing both the rhythm and the rhyme. 65

The Chinese translation, by Wang Dexin, appeared between 2010 and 2017. It is partially rhymed and does not replicate all the special effects. Imposture 17, for example, includes a passage that can be read backward as well as forward. In its Chinese rendition, the passage is monorhymed but not reversible. 66

For a text that is supposedly untranslatable, al-Ḥarīrī’s Impostures has been translated many times. 67 At least four of those translations have succeeded in carrying over many of the original’s distinctive formal features. The more daring renditions have also been the most successful: as far as I can judge, the Hebrew, German, and Russian Impostures, at least, have had a good deal more resonance in those languages than the timid French and English ones have had in theirs. So, if it is worth translating al-Ḥarīrī again, there is no point in producing another literal version. Instead, any new rendering should take its cue from al-Ḥarīzī, Rückert, Hâşim Velî, and the Russian team, and attempt a transculturation into English. Minimally, this means translating the verse as verse, and finding equivalents for the puns, riddles, and palindromes. Admittedly, such equivalents rarely have the same lexical meaning as their originals. But the lexical meaning, in these cases, is not the point. In Imposture 16, for example, al-Ḥārith is amazed that Abū Zayd can produce spontaneous palindromes; what they mean is barely relevant. That is why a translation like “Won ton? Not now!” (§16.5) works perfectly well even though the original says something else (which happens to be almost equally nonsensical). 68 Similarly, the alternation of dotted and undotted letters in §6.6 can be imitated by alternating words of French and words of Germanic origin. Fortunately, there are enough of both in English that the translation can say reasonably close to the lexical meaning of the original. 69

But how does one deal with rhymed prose? In Arabic, Hebrew, and French, there are more rhymes to work with; in German and Russian, words in a sentence can be more freely rearranged to put a rhyming word at the end. But rhyme in English, being harder to produce, calls a great deal of attention to itself. In prose, moreover, it “introduces an air of flippancy,” as Preston put it. 70 The solution I have chosen begins with the recognition that rhyme in Arabic prose produces a kind of markedness, in the sense that linguists use the term. In the Impostures, al-Ḥarīrī’s Arabic is marked for literariness by (among other things) rhymed prose. To replicate it does not require rhyming one’s own prose; rather, it requires finding some other kind of markedness to use instead. In other words, the way out of the untranslatability trap is to give up on the idea that one has to make the English distinctive in the same way as the Arabic. Arabic has rhymed prose, which English (mostly) lacks. But English, unlike the kind of Arabic al-Ḥarīrī is using here, can (for example) be written in a bewildering variety of historical, literary, and global styles. 71 One way to show off English as al-Ḥarīrī meant to show off Arabic is to exploit these possibilities. 72

In putting this principle into practice I have been guided by Raymond Queneau’s Exercices de style. 73 Published in 1947, it tells the same odd little story ninety-nine times, each time in a different style or under a different constraint: as told, for example, by a speaker who cannot make up his mind, by another who is furious about the situation, and by a third who speaks with an English accent. As a model for translating the Impostures, an approach like Queneau’s has several advantages. First, it compensates for the fact that in many cases al-Ḥarīrī’s story is barely developed. What the reader hopes to enjoy is the verbal performance, not the plot. Second, it encourages the reader to look forward to the next story: one never knows what the next constraint will be, or how it will be applied. While both Queneau and al-Ḥarīrī experiment with a variety of styles, there is nothing obviously systematic in their approach, and thus no way to guess what sort of idiom will come next. 74 Third, once the reader knows what the constraint is, he or she can enjoy watching the author’s contortions as he strives to apply it all the way through, a sensation similar to watching someone “walk a tightrope with fettered legs,” as John Dryden described the work of translation.

In applying Queneau’s method to the Impostures, I have adopted three kinds of idiom. The first consists of imitations of particular authors, for example Chaucer (see Imposture 10), Frederick Douglass (34), and Margery Kempe (50). The second consists of global varieties of English, including the Singaporean creole Singlish (3), Scots (14), and Indian (15). And the third consists of specialized jargons, such as management speak (22), legalese (32), and thieves’ cant (42). In each case, the choice of idiom is based on some feature of al-Ḥarīrī’s original. For example, Imposture 4 contains a debate about friendship and reciprocity. Since these are the themes of John Lyly’s Euphues, I rendered the Imposture as a pastiche of Lyly. Similarly, Imposture 27 involves horse thieving and camel rustling, so I put it into the cowboy slang of the American West. In some cases (e.g., Impostures 19 and 23) I have combined two or more styles, based again on some feature of the original. 75 Similarly, the verses in each Imposture are modeled on those of particular English poets, chosen for their connection to the theme or the style of narration.

As the reader will notice, the English verses often use a different idiom than the speech that precedes them. Although this shift in register may be jarring, it corresponds to a fact of life in al-Ḥarīrī’s world as well as our own. In many parts of the world today, people write in Standard English but use a local variety, if not another language, for informal communication. Pre-modern Arabic speakers, similarly, spoke local languages and dialects in the market and at home, but read and wrote in formal Arabic. So when, for example, a Jamaican-speaking Abū Zayd and his “Jafaican”-speaking son produce a formal English poem in §23.6, they are simply being bi- or multi-lingual, as many speakers of both Arabic and English have always been.

Although the periods, authors, and jargons I have imitated come from a wide range of times and places, I have not made a systematic effort to represent every major variety of English. Nor have I attempted to represent “world literature”: I have excluded writers known in English only through translation, since imitating, say, Don Quixote, would for me mean imitating Edith Grossman, rather than Cervantes (who is, however, cited in Spanish in Imposture 16). Apart from the near impossibility of including examples of everything, the most obvious reason for limiting my English sources is that al-Ḥarīrī did not make a systematic effort to represent every major variety of Arabic. Beyond that, some early experiments made it clear that certain English idioms would not work. John Milton, for example, is a major English author, but he is a writer of epics, and there is nothing epic about the Impostures. Also, he is not funny, while al-Ḥarīrī often is. So no Milton, except in a few quotations.

Another self-imposed constraint was chronological. When imitating authors, I discovered that the older they were, the better they sounded as stand-ins for al-Ḥarīrī’s characters. Like al-Ḥarīrī, English authors from Chaucer to Austen lived in a world lit by fire (or gas lamp); the general sameness of the props—horses, swords, inns, and so on—made it possible to put the Impostures into the language of these authors without too much distortion. But as we approach the world of factories, nylon stockings, and Gatling guns, only a few authors could be relied on to supply an idiom that would not be too jarring. These include Melville, who wrote deliberately archaic English; and Woolf, whose stream-of-consciousness technique can arguably be applied to any kind of content. As a practical matter, moreover, the closer we come to the present, the more likely it is that a poem, song, or novel is protected by copyright. Slang and jargon, fortunately, are open-source; and some modern varieties of English, despite being of recent origin, turned out to be extensive enough to supply equivalents for everything al-Ḥarīrī says without relying on modern props. These include Nigerian Pidgin, and—to my surprise—University of California, Los Angeles, slang, circa 2009. Unfortunately, giving disproportionate weight to the pre-modern means that the selection of English authors slants more heavily to the male and white than might otherwise be the case. But heavily does not mean entirely, as the reader will discover.

The use of ethno-specific varieties of speech and writing raises the vexed question of cultural appropriation, a question to which I have given a good deal of thought. I take seriously the argument that privileged users of Standard English have no business imitating, and profiting from the use of, the speech varieties associated with less privileged communities, especially since members of those communities have suffered everything from ridicule to persecution for speaking as they do. But I also take seriously the arguments of linguists and writers, many of them members of the same communities, who point out that ethno-specific forms of speech are fully developed forms of language and therefore no less deserving of serious study than, say, classical Arabic or Standard English. When local varieties of English reach the point, as many have, of being used to compose literary texts, they have for all intents and purposes become full-fledged languages. For better or worse, one of the properties of a language is that it can be learned by non-native speakers. And indeed, every variety I have imitated here has its linguistic anthropologists, textbook authors, and video uploaders eager to pass on the secrets of their talk.

In using these varieties to translate Arabic, I am taking the enthusiasts at their word that their forms of expression are worth sharing. Using a nonstandard variety of English is not the same as mocking its users, speaking for them, or pretending to convey their experience—all habits of privilege that are indeed obnoxious. Rather, it is a matter of treating all varieties as equally worthy of being called upon to represent the staggering diversity and inventiveness of English. Given the nature of the original, moreover, using different idioms did not entail trying to create facsimiles of ordinary talk. Rather, it meant coming up with something as verbally excessive as the Impostures. To do this, I relied primarily on speech and writing by verbally excessive speakers and authors, and on the second place on dictionaries, glossaries, and linguistic studies. In as many cases as possible, I asked a native speaker, a well-informed writer or linguist, or—in the case of historical varieties—an expert reader to review my draft. In one case, that of Naijá (Imposture 45), the review was so extensive that it amounted to a largely new text, which should be read as a collaboration between myself and the Nigerian novelist and editor Richard Ali.

In an essay on the translation of classical Chinese poetry into English, Paul W. Kroll warns against “the idea that it is permissible, even necessary in some cases, to rewrite the original text to accommodate either the deficiencies or the particular strengths of the target language.” This “self-protective approach,” he says, fosters “the tendency to discover simply oneself and one’s own ideas in a text.” When a translator gives in to the urge to “rewrite the text in order to please himself,” the result is a monument to “self-display and the anticipated desires of an intellectually incurious audience” rather than “an honest carrying-over of the original author’s words and thoughts.” Kroll does not deny that an “imitation” (John Dryden’s term) can find a place “in the broad market of literature,” but it should be understood as “a new performance inspired by, but not reliably reflective of, the original text.” 76

Before I met al-Ḥarīrī, I would have agreed with everything Kroll is saying here. Having now learned something about the Impostures and its reception in various languages, I cannot imagine carrying it over honestly without self-display. Nor can I imagine a translation of al-Ḥarīrī that is “reliably reflective of the original text” without being a performance of some kind. In this case, the point of the performance is to create a text that is impossible to read as anything but a celebration of language. If the result does not quite seem to deserve the name of translation, I will happily accept two other names. One is new: transculturation. The other is old: Englishing. 77

While deeply engaged in the Englishing of al-Ḥarīrī, I happened to make the acquaintance of Abdessalam Benabdelali, an accomplished translator and theorist of translation. When I told him about this project, he said simply, “The Impostures cannot be translated.” Before we parted, he kindly gave me a copy of his bilingual volume Ḍiyāfat al-gharīb/L’hospitalité de l’étranger (“Stranger’s Welcome”). Looking at it later, I came across a passage that may explain what he meant:

The untranslatable is the space where the differences between languages and cultures come to the surface. This does not mean that certain things can never be rendered, but rather that we must never stop trying to render them. The untranslatable, therefore, is not something that cannot be translated, but rather something that can be translated infinitely many ways. 78

This I take to mean that all translations fail, but all the failures are necessary. In my work on the Impostures, I have found this a consoling thought. The second thing that has sustained me is not so much a thought as an image: al-Ḥarīrī, blackening page after page, tugging at his beard, and all too often finding himself at a loss for words, as he strove to match wits with the Wonder of the Age.