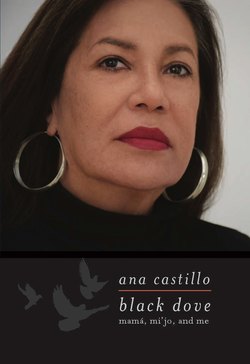

Читать книгу Black Dove - Ana Castillo - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMe in New York (1976).

Peel Me a Girl

My teens were the most uneventful years of my life, but the world around my pubescent self was exploding.

In the sixties, I was but a fleck of lint in the navel of a waking giant, a small-boned girl growing up in a flat smackdab in the middle of a city that made the national news every evening. White, male talking heads narrated daily clips of Vietnam combat and boys dying, maybe the one from next door; Johnson’s War on Poverty was in full throttle with food stamps, Head Start programs, and urban renewal; the Chicago Seven were rock stars; César Chávez fasted for field workers; Jimmy Hoffa was in prison; Bobby and Dr. King were killed in broad daylight and outraged crowds hit the streets with chants and placards. The most famous mayor in Chicago’s history, the boss to beat all bosses, put out a no-shenanigans tolerance edict and sent out thousands of police in riot gear and then national guardsmen to deal with antiwar protesters.

From my back porch we saw smoke rise up from tear gas set off during the Democratic National Convention. The neighborhood I was growing up in had been razed to start building the City of Oz by the twenty-first century. My family was relocated nearby. With blocks of buildings torn down from the back porch, we had a clear view of the gleaming high-rises downtown.

In 1968 I was thirteen and graduated public school as the president of my eighth-grade class. Against my teacher’s advice to send me to a good school, my parents thought I should follow my older (half) siblings’ footsteps and attend the public high school in our district. It was the same school my dad had gone to before dropping out twenty years earlier. Riots had followed the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. A curfew was enforced after that.

My grammar school was mostly black. I still remember the children—kind, smart, and well behaved—my neighbors and friends, Monica, Clifton, and Annette with her curled bangs and starched dresses. A few went to Jane Addams’s Hull House after school, as I did. If our neighborhood hadn’t been torn down we would have grown up together. By the time I reached the fourth grade, my last year before the school was destroyed, however, I was taunted, beaten, bullied, and harassed daily by other kids who were not as welcoming of “the little white girl,” as I was labeled. The main bully was a boy named Odell. After one of his mean attacks, I was called to the principal’s office. Someone had reported the assault, but it was not me. There was no telling what might follow my snitching. A woman waiting in the office eyed me. It was Odell’s mother. Neither of my own parents was there. I can only guess that the school called them at their work, but maybe not. Neither parent ever mentioned anything to me.

“She’s such a pretty little girl,” Odell’s mother said. I was nine, but I couldn’t see what that had to do with her son’s abuse. How was she seeing me? My mother kept my long hair in braids entwined with red ribbons. I always wore gold post earrings and the practical shoes built to last until you outgrew them and homemade dresses below the knee—all emblematic of traditional Mexican girls. As a child, I was still between Spanish and English, speaking mostly Spanish at home.

I knew how to defend myself. I’d given poor Clifton a bloody nose in the school playground for bothering me too much. But Odell was something out of To Sir, with Love, with a motorcycle jacket and combat boots in the fourth grade. He waited one day behind the door of the classroom. When I came in he swung the leather jacket with its buckles and studs smack into my face and sent me reeling.

My family, whose experiences were distanced from that of a young girl in a city fraught with turmoil, didn’t get it. They didn’t want to do anything but go to work at the factory, collect a paycheck, and squeeze a tiny bit of life in on the weekends. My mother, by doing all the housework on Saturday, relaxed on Sundays by visiting her sister and, later, her oldest daughter, who had eloped. With the older half brother drafted and the older half sister married, I helped my mamá clean the flat. She taught me to iron. She did the important items, but it was left to me to press my father’s boxers, handkerchiefs, our sheets, and some of our clothes. This was before permanent-press fabric, which later cut the weekly labor time needed by my mamá and me to one day.

During the week, I was the household’s errand girl, going up and down Little Italy. By ten years old and throughout my teens, I was paying the bills at the currency exchange, mailing packages at the post office, picking up corn tortillas at a local grocer, dropping off my dad’s dress shirts at the cleaners, procuring cigarettes on the sly for an older sibling when one was around, picking up repaired soles from the shoemaker, buying bread from the Italian baker in our neighborhood on Taylor Street, and dropping off prescriptions at the pharmacy. In the evenings during the week, my mother mended what needed to be mended, and she taught me to use her Singer pedal sewing machine.

My father went out on weekends with friends. They put on suits and skinny ties, got in sparkling Cadillacs, and disappeared into the night. I’m not sure where he went on Sundays during the day, but I didn’t see him then, either. Sunday evenings my parents went to bed early in order to rise for work on Monday and start a new week. When they fixed their marriage I was fifteen. The weekend routine remained largely the same except that now my father spent time with my mother.

Now and then, Mamá mentioned the young white protesters outside the factory passing out leaflets as the workers flooded out of one shift and the next poured inside. The pamphlets urged them to join the Communist Party or some Marxist-Leninist branch and go to meetings about the people’s liberation—a liberation for which my mother had little use. One time, one of the pamphleteers got hired and it was Mamá’s duty to train her. At home one evening, as she warmed up our supper of daily frijoles, tortillas, and made some other thing (fideo or arroz or maybe neckbones en chile verde), my mamá shared with a little chuckle how the trainee had come in with dog flea collars around her ankles. The girl had a bedbug issue at home and that had been her unlikely solution. In other words, the idea of these revolutionaries leading any kind of charge was not to be taken seriously.

Racial tensions were high then. I didn’t want to attend a high school where I would be targeted as I was by Odell. The irony about not wanting to go to the local public school was that color and ethnicity were important to me, too, particularly in a white-dominated city. I wasn’t white. You had only to ask what any European-descended individual thought of me. With my reddish-brown hue, indigenous features, and dark hair I inherited mostly from my mother, the usual comment was that I couldn’t even be American.

I identified with popular black culture, though, like many teens of the time. At bedtime, tucked by my pillow was the transistor I got one Christmas. If I kept the volume up just enough, right at my ear so that my mother didn’t know I had it on, I could listen until I zonked out. Bedtime hours were strict since my parents were up by four or five in the morning. “¡Sopla la luz!” Mamá would call out from her room. Whether it was because they had no electricity in México or because she picked it up from her grandfather who came from the nineteenth-century rural world where candles or gaslights were used, my mother’s order was to “blow out the light.” WVON was an all-black radio station and, at night, South Side teens tuned in to hear the latest jams until the wee hours when broadcasting went dead.

Herb Kent the Cool Gent on WVON was a natural born fabulist. Every night he gave installments about metaphorical characters, the Wahoo Man, the Gym-Shoe Creeper (with stinky feet), and the little critters that populated his Afro. They were “green, purple, orange,” he said, and very soon you knew he was telling the story of the city’s current race relations. Herb Kent had the astuteness to make it not only about black and white but also brown—Latinos. He had a smooth voice, Herb did. I imagined a sculpted face like that of Seal or a green-eyed Smokey type but with a big Afro.

While the station played the Temptations or Diana Ross’s latest hits—everything from Motown—they gave shout-outs to mostly black high schools. On my own when it came to education, I ended up at a small girls’ Catholic school before transferring to a secretarial school. Both schools had mixed ethnic populations and girls from working-class families. Neither place had any of the exciting events or associations of big schools: no football or basketball heroes, no bands, no boys, no dressing up how you liked. Neither of my schools allowed teased hair or miniskirts, or slacks for that matter, even during the coldest of Chicago winter days.

On weekends I could dress how I wanted. (Well, not really, because then I was regulated by my mother.) Since I started working at fourteen, I made my own money and got away from my mother’s Salvation Army finds for me, her home-sewn skirts made of random fabric, the occasional store-bought dress on sale. Instead, I treated myself to a pretty empire-style dress or sling-back shoes with low pointed heels. I didn’t wear much makeup, but I applied eyeliner with wings at the ends à la Ronnie from the Ronettes, and I remember there was a time when my crowd thought smudging under-eye cover on your lips to give you a neutral lip color was the height of chic.

When I was fourteen and fifteen I danced at the YMCA Friday night socials to James Brown’s “Say It Loud,” but by 1970 the city was at a no-turning-back point for Black Power and social change. Not only had a Democratic president been assassinated but his brother, who would have likely run for president and was one of the greatest leaders for black civil rights the country had ever seen, was shot dead in broad daylight. That day everyone was sent home from school and told to lock their doors.

In this atmosphere—with mostly absent parents, an inner-city girl with inner-city tastes and dance moves, around inner-city boys who’d dropped out of high school and joined the army or were drafted—I came of age. I caught sight of Herb Kent on the TV console in our living room one afternoon, probably during the King riots when the city was again in an uproar. He turned out to be frog eyed and thin as a Popsicle stick. What a shock. But by then I was developing something of an identity, which comes part and parcel with being a teen. That identity was neither black nor white.

Where were my people? They were around. Puerto Rican activists were demanding a new high school in their neighborhood, and afterward, Mexican Americans did likewise in theirs. There were protests. I remember taking off from my after-school job to shout “¡Viva la raza!” and raising my fist at city hall until I was hoarse, although I don’t remember what exactly we were protesting on that occasion.

Not that we didn’t have ample cause. No, not all men had been created equal in the country, and women, despite their right to vote, most certainly were not seen as equal to men. Right after I graduated from high school, I stopped wearing a bra, and a Mexican college boy I dated told me he didn’t think a nice girl should go around like that. I always have liked my breasts, even if I found them mostly obtrusive, and I defended my new right to not be forced into constrictive body armor.

That was my assertive self. Another part was struggling, feeling like an outsider. During those years, I would have liked to have a mother to talk with—or a father. Instead, my parents showed little interest in the young woman growing up under their roof, who spent most of her time in her room in the manner of all teenagers, who cried quietly or loudly and either way was ignored.

I began to suffer periods of catatonia. It was clear to me that my mother was aware of this disturbing affliction because her response was to yell at me from the kitchen that if I kept it up she’d lock me up in the psychiatric hospital not far from our neighborhood. This catatonia stayed with me until my midtwenties. I don’t remember any episodes after the age of twenty-four. I didn’t know why I couldn’t talk at times. I just couldn’t and wouldn’t. When I shut down, you could come at me flailing a medieval spiked ball and my lips wouldn’t have parted.

My two high schools had been small and, how I recall it, there were various cliques that were “in.” If you were athletic, let’s say, that was one way to be admired or at least respected. Of course, if you were very pretty, girls and teachers both liked you. I had my experiences of being both “in” at times and, at others, singled out. At fourteen, my most awkward teen year, I was lanky and felt plain. Previously an active kid, I was now clumsy at sports. By fifteen I started to make an effort to keep up with cool girls.

As a senior I was in the Spanish club, which was mostly native Spanish speaking girls, and I don’t think I spent much time with them. Their first language was Spanish and my Spanish was so-so. Instead, I’d started a kind of underground paper about the eminent revolution. I did almost all the writing and illustrations (I think I drew the red-winged woman straddling a conga on Santana’s Abraxas album cover for my own cover.) I also did the publishing (i.e., xeroxing at my job on the sneak) and distribution (the school). The girls from the Spanish Club gave everyone a title at the end of the year. Mine was “Miss Intelligent.”

I had an after-school clique, not necessarily girls from my school—in fact, a few much older. Our hanging out was a Latina version of Iceberg Slim pulp fiction. A digression: Yes, I had read Iceberg Slim by then. I read anything that came across my field of vision. I’d found a box of his paperbacks hidden underneath my parents’ bed. What was I doing under my parents’ bed? My mother had a habit of hiding things. It might be the packaged cupcake snacks or oranges she kept exclusively for herself to have with her week-old bread sandwiches on her thirty-minute lunch break at the factory. (She said she wasn’t hiding them from me but from my older half sibling who notoriously ate everything when he was around.) It might have been my transistor radio if she’d gotten mad and took it away because I had played it at night and kept her up.

My nosiness paid off with the book discovery; I cut school and read them all. I never knew why my father had those books. At home I only saw him reading the daily newspaper. Now that I think of it, maybe he read them on his breaks at the factory and kept them out of sight at home because of their cover illustrations of pimps and sultry streetwalkers. These were stories told of a backstreet lifestyle that Slim had experienced firsthand, in and out of jail. He was an excellent spinner of seedy tales.

When I graduated from high school and took a full-time job in an office downtown, I used to stop in the sundry shop off the lobby in the high-rise for cigarettes. I started smoking that summer because I was eighteen and could do what I wanted. Like Alice Cooper, I loved it, liked it, loved being eighteen. I’d spin the paperback rack for something to read on the bus ride to and from work. The books I found and still have were Zelda (about the wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald), The Other (a movie based on the novel came out around then), and The Naked Soul of Iceberg Slim.

Back to being a high school freshman: I don’t know what I’d have done if either of my parents had come home and found me sprawled on the living-room floor surrounded by all the paperbacks apparently viewed by them as hardcore porn. My mother might have threatened me again with the insane asylum. But they never came home unexpectedly from work, ever. They never missed work. They never called home to check in during the day. You were not allowed to call the factory and interrupt their machines and quotas. And when the school eventually reported to my mother (unable to reach her, the nuns actually came on a weekend morning to catch her at home) about my excessive ditching of school, neither did anything about it. It was a Sunday, Mamá’s only real rest day, and she couldn’t have been happy with the visit. I may have had a catatonic adolescent depression, but my mother didn’t like to talk to anybody on principle. My father was sleeping off a hangover.

Mamá wasn’t very religious, so the nuns didn’t connect with her. The school was my choice, and with my after-school job I paid my own tuition anyway. As an orphan, being made to work as a domestic as a child, Mamá never attended catechism. She said she was Catholic but she couldn’t take communion. My mother was an outsider all her life. Maybe she passed this feeling of exclusion from everything on to me the way some parents inadvertently pass on OCD behaviors.

When I wasn’t home in a state of antisocial withdrawal, I went to see some girls I knew; the quasi–Iceberg Slim, late-sixties Latina version of our crew is in my mind. They were around nineteen to twenty-one years old for the most part, but there were a few precocious younger girls. One thirteen-year-old became pregnant. She was white and when the mother let the boyfriend stay over, I couldn’t help thinking if that were me getting caught having sex, far from inviting the punk to have a sleepover, my mother would have taken me to an abortionist, then locked me up in the psychiatric hospital until I was eighteen. Only God could have helped the kid when she caught up with him. Why my folks were guarding my virginity is hard to say. There was no dowry to be had. In 1968 the pill had barely made its entrance into the world, and until we mastered birth control, sex and getting pregnant for the inexperienced were synonymous. My parents were adamant that nobody birth babies they could not afford. I was lucky my father had agreed to have me.

Memories of those young women I fell in with when I was fourteen abound. There was stunning, slender, dark Puerto Rican Carmen, whose brother, Edgar or Edwin, closer to my age, was in the clique. No cool guy ever paid attention to me when I was fourteen, at least no positive attention. Edgar or Edwin was the epitome of cool. Sleek, silent, and meticulous in a black cashmere coat and polished shoes. One time a tall, sloppy guy who went by Shadow picked me up without warning and slung me over his shoulder, caveman style. On another evening Herc (for Hercules) led me to an abandoned building to make out. I didn’t know what else he had done, but two of my friends explained it was “dry humping.” Those girls, my age, often ridiculed me for my naïveté as well as for my use of multisyllabic words. One school friend’s brother who answered the phone when I called her one time made fun of my deep voice. His spoiled kid sister sounded like a five-year-old. In all kinds of ways, I didn’t fit in at fourteen.

On the other hand, the older girls didn’t care one way or the other about whether I went with any boys or not. They might offer me a Seagram’s and Coke. They sat around drinking while they smoked, blowing sexy rings in the air. I didn’t care for any of that. I liked listening to 45s on a portable record player and doing the soulful strut or singing along with new hits like “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” or oldies like “Angel Baby.” I did a decent “Hello Stranger,” with two of my girls as backup, having a sultry voice at fourteen and all.

One summer evening, I dropped by Carmen’s flat. Carmen was in the middle of a fight with her boyfriend, “Moose,” a very tall, fair, good-looking Puerto Rican. He was gone when I arrived. Carmen was very upset and I agreed to walk around the block with her.