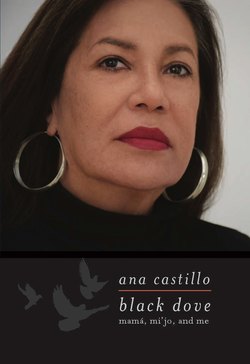

Читать книгу Black Dove - Ana Castillo - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMy grandparents María de Jesús and Santos Rocha and their son, Rudolfo.

Introduction

Perhaps some of you may come away from this book feeling that my stories have nothing to do with your lives. You may find the interest I’ve had in my ancestors as they were shaped by the politics of their times, irrelevant to your own history. My story, as a brown, bisexual, strapped writer and mother, constantly scrambling to take care of my work and my child, might be similarly inconsequential. However, I beg your indulgence and a bit of faith to believe that maybe on the big Scrabble board of life we will eventually cross ways and make sense to each other.

If you reside in the United States, whether you are able to vote or pay taxes, then know that you and I have much more in common than not. Know that we may differ greatly in opinion, but only a handful in the world make decisions that affect the majority, and that majority includes you and me. If we question what passes for truth or the veracity of any point of view, these days bombarded and overloaded as we are with random sound bites, know also that knowledge sets you free. Knowledge makes you strong. Not scattershot information gleaned off the Internet or the opinions of Facebook friends, but checking and cross-checking your resources, going to the source, radical curiosity—that kind of knowledge.

I focus my observations on my own background because it has been critical throughout my life to find out who I am. You see, I never saw me in history books. I didn’t find women who looked like me in the Edna St. Vincent Millay sonnets I fell in love with at sixteen in my secretarial school’s library. That wasn’t me or my mother in the paintings I studied at my beloved Art Institute of Chicago. I didn’t see us on television or at the symphony or the ballet. We weren’t in white smocks in hospitals or running for office. In public schools, I grew up without a single Latino instructor with whom to identify; indeed, I had none in college. The Latino student organization I participated in demanded a Chicano instructor and we finally prevailed in my last year, welcoming a young ABD sociologist not much older than those of us he’d teach. And yes, having that changed my life. What I heard in his class left me astounded and affirmed.

You may be interested in math and science or business and profit. You might want to work with destitute children in faraway places, or you may be wishing for the chance to make enough money to buy your mother a home someday to say you achieved your dream. We all aspire to something, which is why we are here. The dreams vary, but we remain in the same world at the same time. My message to you, the next generation of dreamers, begins with a summary of an earlier generation—not mine, but that of my grandmother.

We all know that this young and mighty country in which we live was built on the literal blood, sweat, and tears of many people from diverse backgrounds and places. The United States is a young country, because in comparison to civilizations that go back millennia—Egypt, China, Japan, the Incas, Rome—it is a scant couple hundred plus change years old. When it was about half its age, right before the twentieth century, there was great energy and excitement in building a railroad system that would revolutionize exports and imports and continue this country’s prosperity. The president of México and the US government worked jointly on this effort. It was a time of enormous gains for the United States. For México, not so much—except for the few in power who became rich. Then they had a civil war. As a result of the Mexican Revolution a hundred years ago, my paternal ancestors migrated north and settled in Chicago. My father was born in that city of unforgiving winters and steamy beach summers, asphalt all around and the factories that Jane Addams so protested, the reeking slaughterhouse on Halsted and black fume-releasing oil refineries and the steel mills of the South Side. I was born in the same city and grew up in the same neighborhood as he had.

My mother’s father was from Guanajuato, México. He was a signalman with the railroad and part of the great frenzy of prospering times. We like to say in this country that if you work hard you can have a piece of the pie. Apparently, he got his, traveling with his young bride, sometime around 1918, north, where they lived for seven years before their first child was born in Kansas. I have pictures in my study of my lovely grandmother in her wide-brimmed hat, chemise dress, and pearls, and my grandfather with his handlebar mustache and pocket watch, in front of their car. Their son posed in a photo studio in his tweed suit and cap. My mother came along two years later in Nebraska in 1927. There are sepia pictures of her, too. Sweet. The infant is sitting up with a knitted sweater over her pretty dress. Had the mother made it for her child? Did she find the day too chilled in Nebraska and fear her baby might catch a draft?

As you may know (or not, I will tell you anyway) the history of the country includes the liberal importation of labor during times of growth. My grandparents were a part of this migration. The European settlers had suppressed, enslaved, and eliminated indigenous peoples; the survivors were sent to reservations. This is not the old days, or once-upon-a-time talk. We still have reservations in this country. They are not on the most fertile lands. Poverty and all the stigmas that affect demeaned communities are present. High suicide and drug rates hobble the youth in an already dwindling population. Let’s take a second to think about that reality—tracts of depleted land for the original peoples of this land. And consider, too, the slave labor brought from across the seas. Even the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 did not fully bring former slaves into the democratic fold.

At the end of the nineteenth century and the start of the next, Mexicans had their own dark history with the US government. At that time, they were willing, eager, and able to lay down tracks and pick cotton. Mind you, the Border Patrol wasn’t established until 1924, so people came back and forth freely. In fact, the Border Patrol wasn’t established at first to keep out Mexicans. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed by Congress to prevent immigration from China via México. This was the first significant law restricting immigration to the United States.

But wait, a lot of people were coming in at that time. They came with whatever they had in their hands and on their backs, along with their dreams, to Ellis Island. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and into the early decades of the twentieth century, new Europeans arrived and were faced with animosity. Historians have documented the racist and ethnic prejudices that each group experienced for at least a generation before assimilating. “Everyone had to pay his or her dues” before being allowed entry into the American Club, as the adage went.

Ellis Island in New York was the destination point for a second wave of immigration from 1892 to 1954. But decades before Ellis Island opened as a processing center, New York had already received around eight million immigrants. The Great Potato Famine caused many Irish to immigrate to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. Legislature denied entrance to a few—convicts, “lunatics and idiots,” people with no means to take care of themselves, prostitutes, labor brokers, the Chinese—in other words, the usual suspects.

If you were more or less healthy and could prove you would not be a burden on society, you got to stay. Conveniently, on the East Coast, the Germans and Irish (who were not part of the Anglo-Saxon political elite) were able to expedite citizenship at voting time and gain full entrance into society. Approximately twenty to thirty thousand men (and their families) were naturalized in New York City in 1868 alone in the weeks before that year’s presidential election. Briefly, in the eighteenth century, after five years of residence, European arrivals could apply for citizenship and, in fact, when they first arrived, were encouraged to do so as part of their assimilation.

Earlier, around 1840, lawmakers in Washington turned their sights to the vast territories of the Southwest pertaining to México, justifying their dreams for grandiosity with the ideology of Manifest Destiny. An invasion was executed, followed by a brief war and a surrender. Half of México became part of the United States in 1848. To coax people to establish the West, the government sold land cheaply to citizens and European immigrants alike. Long-established hacendados, ranchers, and landowners—formerly Mexican—often lost their properties in strange maneuvers manipulated by the new government.

Fast-forward seventy years, zooming prosperity came to a sudden halt with the Stock Market Crash of 1929. The country could not sustain itself. The Great Depression began. Measures were taken and the labor provided by Mexicans was undesired. The nation needed rescuing, and it was thought then that Mexicans and US citizens of Mexican descent shouldn’t just get in the back of the line, they should leave altogether. Vamos. The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was determined to “repatriate” Mexicans and their American-born children. Sometimes they did it with a train ticket, others were pressured and threatened. Sixty percent of those deported were American citizens. Undergoing its own economic crisis, the Mexican government was unable to accommodate or provide for these repatriated families, so recently part of the American Dream. It has been estimated by historians and acknowledged by US Citizenship and Immigration Services that in the two years after the crash, at least two hundred thousand Mexicans left the United States. Over the next ten years, altogether an estimated four hundred thousand to one million Mexicans and Mexican Americans were deported to México.

Soon after my maternal family was repatriated, my mother’s father died. When my mother was nine, her mother, too, passed, most likely of tuberculosis, leaving her an orphan. She, along with her brother, Tío Leonel, and sister, Tía Flora, and other cousins affected by the repatriation, lived with their grandparents, people of humble means. My mother, an American citizen born in a middle-class home in the Midwest, found herself now growing up in México. Without other options, she went to work as a live-in servant. Years later, the grandparents brought the young-adult grandchildren as far as the border, encouraged their return to the United States to find work, and hoped for the best.

My mother lived and worked in Chicago for the rest of her life. But, a funny thing, I never knew her to speak English. She had mostly worked in factories, on assembly lines. Foremen were gringos—she had to understand some English. My parents subscribed to the Chicago Sun-Times, which she read. She sold Avon for thirty-eight years, until her death. Still, her refusal to speak English at home convinced me that she didn’t understand. “¿Qué? No te entiendo,” she’d say to me.

To think that less than a hundred years ago, up to a million people were corralled, harassed, and handed orders as private citizens to leave this country. They were told to leave hard-earned good lives behind, lives that might’ve included work, property, family, community, church, and future plans. This seems a monumentally sad, unimaginative way to fix a fallen economy.

¿Qué? No lo entiendo, I say to you.