Читать книгу Black Dove - Ana Castillo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

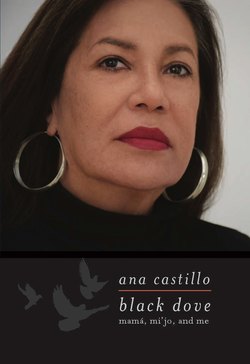

ОглавлениеMamá, age 17, New Year’s (Laredo, TX; 1944).

Remembering Las Cartoneras

At the turn of the century, people everywhere were making plans to travel to a place that was meaningful to them, a place that would make them feel ever so glad to be alive, witnessing the ushering in of the third millennium. Throughout the 1990s, the United States was deep in the embrace of the American Dream, and it seemed the nation had nothing but more of the same to look forward to in the new century. My tía Flora, the mother of five, grandmother of eighteen, and great-grandma to nine, who had not taken a vacation in over twenty years and had not even so much as flown on a plane before, was no exception.

In 2000, without discussing her plan with anyone (except with her late husband and my mother and father, who were her confidants in heaven now, she said), Flora booked a couple of tickets, grabbed a young grandson, and, using the stocky seven-year-old in lieu of a walker, forced her arthritic legs to board a direct flight to Mexico City—El De Efe—place of her birth.

At seventeen, my tía Flora left México. She started the march north, the same route as my mother before her, stopping for a short time in Nuevo Laredo where their grandparents had relocated. It was a strategic move to be close to the Border where their grandchildren might cross over to work. As a new bride with a Tex-Mex husband and small children in tow, Flora next traveled to Chicago and stayed for life. The city was idyllic to my aunt. It became her “Paris,” she came to say as the years passed, with its pristine parks, Magnificent Mile (where a woman with little means could still window shop even if she couldn’t go in to buy), its lively summer street fairs and snowy winters.

Her new husband took a job in a factory, and once all the children started school, she applied for work as a seamstress in a small upholstery company. “I’d never used a sewing machine before in my life,” she told me back then, “but when the owner asked if I could handle it, I said, ‘Yes, of course I could’ and did. He never regretted hiring me and I never let him down. I loved all the years I worked there. I loved my fellow seamstresses, even the cheap-minded owner!”

My aunt did not use the word “love.” She said “encantada,” which in English means “enchanted” and which could not have been what she felt eight hours a day, the same foot pushing an industrial Singer pedal, developing arthritis, fingers pricked to the point of numbness, getting carpal tunnel syndrome as the years wore on, earnestly working toward each hour’s quota. It was my tía Flora who was enchanted.

True, her whole life was devoid of privilege. She had scarcely known her mother, who died when she was but a small child. Her father eked out a living selling used books on the street, and providing for his children was impossible. She spent her adolescence as a live-in servant in Mexico City. Yet there was something about Flora that, as perfume commercials suggest about a woman with an alluring scent, emitted a touch of class, style, a dash of crimson across an otherwise gray palette. Not glamour, fancy jewelry, or extravagant parties, but a taste for life, the joie de vivre that eludes so many.

It was in the details, as I noticed even as a child when I spent a few New Year’s Eves with her and my five cousins. (Where her husband was, I never knew. My own parents were out for the night—although not together). My mother, who never went out, made New Year’s Eve the exception. My tía Flora, perhaps by default, was our sitter and, without a word of complaint, set a formal table for us children with the silverware in place as if we were adults and important. She served us each small portions of luxurious steak. We drank Tang or milk from her best glasses. Twelve purple grapes waited in small bowls for the striking of midnight, when each one devoured represented a wish for each month of the coming year. We couldn’t afford new red underwear for good luck, but she’d given us red and yellow balloons to blow up and pins to pop them with after midnight. We each took a turn stepping out to the apartment hall and coming back in with an empty valise—to ensure a fun trip in the coming year (to children of people without automobiles and who never took vacations).

These Mexican rituals were “the way a year should start,” Tía Flora thought, with the best of everything laid out and sending out all your hopes and desires. Pop, pop, pop, kiss, kiss, and kiss. What we children wished for, I don’t recall. A reasonable guess would be for a bike or something along those lines. What my lovely young aunt wished for, however, I can only speculate.

Throughout the years on special occasions there were embroidered napkins at the dining-room table where Tía Flora served up exquisite meals in her tiny flat in a one-hundred-or-so-year-old brick tenement that she and her husband eventually mortgaged. The bedroom was tiny-tiny, and the back hallway ended up serving as a clothes closet and storage space. Yet, there was the wearing of a hat and gloves to church in the days of Jackie Kennedy, the elegant sling-back low heels, the margaritas Tía Flora made and served in martini glasses. When she let you hear it, her pitch-perfect singing voice—“Cucurrucucu Paloma.” Where my aunt got her panache, I never knew. She simply had it.

One of my favorite stories regarding my tía Flora, who was not just my aunt but became a friend (meaning, once I was grown, we often enjoyed a good “just between us girls” laugh together), took place in the 1970s when she would have been in her forties. Tía Flora and my mother did not share the same father; their widowed mother remarried before dying young. My mother’s father, from his photographs, was evidently indio. They were from the state of Guanajuato, which is inland. Tía Flora’s father came from the port city of Veracruz, where ships once arrived carrying slaves from Africa. Veracruz is permeated with Caribbean culture: marimbas and fried plantains, tall “mulattos” (as they were known and how my mamá’s half sister would also have been seen), and palm breezes coming in from now oil-spilled beaches.

Tía Flora inherited her father’s kinky hair, which she always kept closely cropped, a look that enhanced her pretty face with the large gold hoop earrings she favored most of her life. She was certain she also got her love of music from this father she hardly knew, who gave her no reason to think so but who, she came to believe, had come to México by boat from Cuba as a young sailor or stowaway. (He did bear the same surname as the island’s revolutionary dictator, after all.) Ah, what difference would it all make? Tía Flora thought, cherishing the notion of a bloodline to Havana. Before the Cuban Revolution, when Tía Flora spent her teen years working in the kitchen of a private residence in la capital, she listened to Benny Moré, Cachao López, and Miguel Matamoros, who brought their sones, boleros, and mambos from that country to México.

She was a girl dreaming like all teens dreamed, and what she began to dream about was an island where the air smelled of butterfly jasmine, young people spent their evenings sipping rum drinks from coconuts and eating guava sweets, a far-off land surrounded by salt water—nothing like the asphalt density of Mexico City, where she was born and grew into a young woman with generous hips that swished to a palm rhythm of their own when she walked.

My aunt never made it to Havana. She never danced to “Lagrimas Negras” under a Cuban moon. She never worked her naturally copper-colored body into a swimsuit to lie out on a beach, not in Havana, Veracruz, or later in Chicago, where she and my mother took all of us children to the Twelfth Street Beach plenty of times during the summers. Neither of them went in to bathe with us splashing, tireless children. They watched from the shore with sandy tacos wrapped in wax paper and hard-boiled eggs and Kool-Aid in a big thermos, all of which we had carried on the very long jaunt from our inner-city flats. Too many unruly kids to pile on a bus might have been their thinking. (Or anything to save a buck, which could have been my mother’s motto.)

When she was old enough, maybe fifteen or sixteen, Flora left the kitchen she grew up working in and, soon after arriving in Nuevo Laredo to join her grandparents, married a soldier. After two children and before the age of twenty, she was widowed. She remarried—a Tex-Mex field worker with a pencil-thin mustache and Western boots—and my mother urged her younger sister and the new husband to come up north to Chicago. My aunt had learned to cook a wide range of delicacies, and she had no problem adding to her menu her norteño husband’s preferences: flour tortillas, pinto beans, fried potatoes and eggs, and, of course, lots of red meat. Tía Flora was never a woman who liked to argue, so she kept her husband happy. But she did love to dance, which he did not. Unfortunately, the cowboy husband never came around, not even to slow dance to please his wife.

By the seventies, salsa was all the rage. Tía Flora developed an ear for the hot rhythms coming in from New York to Chicago, turning them on low on the radio or tuning in to watch the bands on the Spanish channel on the portable TV she kept in the kitchen to keep up with the popular telenovelas. Not normally the jealous type, my aunt’s husband resented the swashbuckling actor, Andrés García, who was a regular on the Spanish soaps.

One time, my aunt vividly recounted to me over one of our savory lunches, her husband had had it with her mooning over the actor. Andrés García not only always got the girl, he even got the wives watching him on TV. My aunt’s husband said as much as he walked passed the little TV and finished off his resentment with an actual hard kick to the set. Sparks flew out of the picture tube. He went out the back door, smug and satisfied. My tía Flora stood stunned by the stove, where she had gotten a clear view of it all from a few feet away. Her husband had slammed the door behind him. By the time he got downstairs and went outside, however, if it wasn’t for her whistle that gave him just enough warning to get out of the way, the busted television she dropped from the second floor window would have landed right on his head.

That wasn’t the story I wanted to share about my live-wire tía Flora, although that one was a good one, too. We were friends, confidantes, as I have already mentioned, mostly in the way traditional married women with children had friends—in the kitchen while preparing meals, quick chats on the phone between chores, at family gatherings when others’ ears were not close enough to pick up private anecdotes. My aunt was the family woman and I had grown into the career woman of the new generation, symbol of hope for possible true liberation from men’s incessant needs and demands.

My mother, from whom no doubt I acquired the somber manner that has so often been misinterpreted as aloofness, was so different from her only sister. I’ve always been attracted to the gaiety displayed by some extroverts. My aunt brought out the deep, hidden lust for life in me that I am very certain she also had and, for our individual reasons, we usually kept beneath the surface of daily affairs. Over the years, as a grown-up, (unlike with my mamá) it was my aunt who received my stories without judgment—news of the public life that evolved from writing, my ended relationships, my comings and goings. One time, Flora told me that in a conversation my mother had expressed concern that I might or could write about our family. My aunt told me she replied, “I don’t care if she writes about me. She’ll make me immortal!”

There is another story my tía Flora shared with me during one of those moments stolen from her endless duties to a large family, work, and husband, whom, as I recall, did little else but drink. Before the drink took over, he worked at a factory. After that, I rarely recall him not swaying. He also made a couple of benign passes at me, which I did not mention to my aunt, even after she surprised me one day when we were alone and shared how her husband had said how fine I looked. One day when he was perhaps in his sixties, Flora found her man dropped dead on the linoleum floor.

The account I remember fondly had to do with the super salsera Celia Cruz. This was before the singer exploded into galactic stardom, before the pink wigs when she became a parody of herself (while still putting out hits), and before her right-wing declarations. I’m speaking of the era when la gente could just go to whatever ballroom Celia with a band of salsa kings came to play at and dance their socks off.

My tía’s Celia Cruz remembrance was another example of getting the last say with her husband, with whom, she swore after his death, she was passionately in love all their days. All that week the radio had been announcing Celia Cruz’s concert coming up on Saturday at Chicago’s famous Aragon Ballroom. The Aragon was situated clear across town from my tía’s casita in the barrio. Her husband had only one female performer for whom he would have spit shined his boots and gone to see and that was Lucha Villa, the ranchera singer who, it was my tía’s opinion, sounded like a lovesick ewe. Short of Villa’s appearances, he was not interested in the crowds, the price of concert tickets, and most of all, acting all a fool on the dance floor.

Flora, though, had no intentions of missing out. It was only a question of how to pull it off. She made a plan. On Saturday, she went about the house doing her chores. Like many working Mexican women who had the custom of wearing the kind of apron that buttoned down the front and had convenient pockets, my tía Flora always wore hers, even to the market. Her favorite mercado, a good mile walk away from her front steps, was stocked with every ingredient a fine cocinera like her might require. When Flora’s husband came in that day (he spent his weekends going in and out until late evening when he’d come in with a six-pack to settle in for the night), she said, cheerfully, “I feel like cooking something . . . rico tonight. How ’bout it? Care to join me for a late supper?”

If you’d ever tasted her dishes, your eyes would have lit up like her husband’s must have at the invitation. Saturday was date night for the two and she said, “Don’t wait around for me, Viejo, I’ve got a few special items I’ll have to pick up.” She knew her husband well enough, who, indeed, did not wait around and made his way back to the corner tavern to wait until she’d send one of the kids for him to come have his supper.

My tía dashed on her plum-colored lipstick, the only makeup she ever wore (or needed, I would add, having the gift of a flawless complexion and bright dark eyes), and tucked her change purse into her apron pocket. She hurried off to the main intersection. In apron and chanclas, Flora caught a cab right quick that zoomed her across town to the Celia Cruz concert. “Come back for me in an hour,” she instructed the cab driver, jumped out, went directly in, and made her way through the crowd until she reached the front of the stage. “Hija, I danced by myself and made eye contact with Celia, and the young men standing around just looked at me, maybe thinking, ‘And this loca old woman?’ I didn’t care, I got to hear my Celia and I was happy.”

An hour later she jumped back in the cab and went home. “What happened to the groceries you had gone for?” I asked. “What happened to the special meal you said you would prepare?”

“Egh!” my tía Flora responded with a toss of a hand as if she couldn’t have cared less. “I simply said that the market was closed when I got there. I was in a very good mood when he came home that night, if you get my meaning, and in the end, Hija, a man can be satisfied by other ways than food.”

My aunt never spoke of herself as beautiful, but she couldn’t deny the sexual allure she evoked in men everywhere she went. Allure that came with sly smiles, meaningful side-glances, and other subtle gestures of unabashed flirtation. I still remember as a small child witnessing her in action with the butchers making sure she got the best cut of meat.

I hardly ever recall my mother flirting with anyone, not even with my father, who was a ladies’ man. But when he was dying of cancer in his midfifties, Mamá became affectionate with him in front of others. He had never been so with her and, although he was weak and spiritually vulnerable, it was apparent he still did not feel comfortable with displays of affection between them.

The time I remember Mamá’s flirtations, they were so unabashed, unlike the intrigue I felt when I’d see my aunt in action, who seemed to possess a kind of Golden Era Mexican-film-star treasure trove of nonverbal sexual innuendo. My mother’s flirtation appalled me. Later, when my father’s philandering became known and I had a better sense of sexuality as a possible outlet for repressed frustrations at life in general, I wished to hell my mother would go out and get laid. She didn’t, even after my father’s passing. Even as she aged, though, Tía Flora’s allure never diminished.

When my aunt was in her seventies, I saw her effortless ability to attract men. She and I were waiting in line for tickets at the House of Blues on one of those iced-over nights that have given Chicago winters their renown. We were not waiting to see Celia Cruz but, now, Albita, a new generation salsera. My tía dressed, as always, in a modest but smart ensemble, both of us in wool overcoats that reached midcalf. We were in the long line when an attractive white man, the cashmere-coat-downtown-type, came directly toward us. Handing us a pair of tickets, he said, “I just got an emergency call. Enjoy, ladies.” As always, my tía was unassuming about the incident and we happily went right into the large hall.

It was early and the crowd was just starting to arrive. Salsa music was playing over the speakers. We were looking around to see where we might situate ourselves, when yet another handsome man approached us—or rather her—again. This gentleman, in suit and tie, was most definitely age appropriate for my aunt. “Would you like to dance?” he asked. ¿Bailamos? With her usual graceful manner, her thick gold hoop earrings catching a glimmer of the light in the dim hall, not looking him directly in the eye (that would have been crass) but with an ever-so-discreet side-glance, she said, “In a while.” Después. The caballero gave a slight nod and returned to the bar to wait.

Getting back to the end of the old century when the world was still good and all that Americans had to concern themselves with was the sexual morality of their president, Flora decided to make the journey back to Mexico City. Apparently, she had unfinished business.

Tía Flora’s youngest brother who stayed in Mexico City left no fewer than ten children as his only legacy. They were all waiting at the airport, grown, many married with children, to greet the from-far-away aunt. (Or at least nine of them—the oldest had made his way to the United States.) The nephews and nieces had a week’s itinerary all arranged: a visit to the neighborhood of her childhood; a stop at Santa Inés Church where she was baptized, one of the few places of her childhood that remained relatively unchanged except that it was somewhat tilting a little like everything else. (Mexico City was built on swampland by the wandering Aztecs/Mexicas.) Flora and family meandered through charming Xochimilco, a pre-Columbian mini-Venice of canals, and went on a day excursion to the picturesque town of Tepotzotlán. They ate tongue tacos on the street as she did as a girl and dined at an upscale restaurant with “típico” decor along with the tourists.

Above all, what my life-loving aunt wanted to do, however, was go to the Salón Los Angeles. The old ballroom, which opened its doors in the thirties, still featured cabaret shows and a dance floor where you could danzón the night away. In its prime, it was a premier joint for the best bands of danzón music around. “If you don’t know El Los Angeles, you don’t know México,” remained its slogan.

As my mother and her siblings were orphaned and otherwise on their own, necessity forced the young girls to work at a very early age; by fifteen, my mother was full-time at a factory that made cardboard boxes. It was 1942, and, as my aunt remembered it, my mother, along with two other girl cousins, all of whom worked at the same factory, would dress up after work, put on their red lipstick, slip into their best dresses and high-heel dancing shoes, and make their way to the Los Angeles cabaret. Little Flora waited up nights to hear the tales from the older girls about their adventures at the famed ballroom. It wasn’t the kind of place where you’d ever meet a serious boyfriend, but a girl could sure dance and forget for a moment that at 7:00 a.m. she’d be back making boxes at the factory.

My aunt recalled the older girls recounting in the shadows of their room while they undressed and readied for sleep how the band leader always dedicated a number to my mother and her cousins: “This one’s going out to the carton girls!” ¡Para las cartoneras!

It made the teens feel a little like celebrities.

Still a child then, my aunt didn’t get to be one of “las cartoneras” at the Los Angeles. Here was the rub for Flora, who not only missed Havana’s heyday before la revolución but, because she married so young, missed everything everywhere. That’s what my tía Flora wanted most of all out of her trip to Mexico City: to dance just once at the Los Angeles. So her nieces, anxious to please their beloved aunt who never came to visit and might never come again and, as it turned out, never did, got dressed up and took her to the shady district of la colonia Guerrero where the Los Angeles still put on shows.

The septuagenarian was thrilled watching the cabaret, she said. It was La Aventurera, about a cabaret worker. The legendary composer Agustín Lara’s famous song may have been the inspiration. Flora’s heart palpitated just as if she had been a teenage cartonera seeing the show for the first time. She even got an autograph from one of the stars (I might add, from the picture on the CD cover, a star who was probably performing there back in the days of las cartoneras). After the show, when the ballroom music began and the old-timers went out to dance, a gentleman (not surprisingly) invited her onto the dance floor. Where did that chronic arthritic pain go? she asked herself. It actually seemed to have disappeared since she had stepped off the plane. “Crafty old knees,” she decided. “They only hurt when they’re not where they want to be!”

It was nearly closing time and as she was leaving, content to have realized a lifelong desire, she saw a woman about her own age dancing alone. “Well, I just put my bag down, went over to her, grabbed her up, and we started dancing together,” Tía Flora told me. “She didn’t say a word to me, just smiled and let me lead!” My tía laughed. When she laughed, she got a little self-conscious about her dentures and tried to jiggle them to make sure they were on tight. “I guess that old woman was nostalgic about old times too,” my aunt ended her account. “Even the old times we never had!” she added, and then laughed again. She shared with me her souvenirs, the signed posters, music, and all the photographs. “I’ve done it, now,” she told me. “My heart will finally rest easy knowing that at least once I got to dance at El Salón Los Angeles. Whoever said you can’t go home again?”

Home, in the case of my favorite aunt, was made of not so much the facts but the fiction of her life, the dreams spun in the kitchen she grew up working in, the lovers that might have been, fantasies offered by television infused into a passionate heart—the stuff and stories that gave her life resiliency.

Once, in her silver years, my tía Flora told me over the phone, “It happened for me last night, Hija. Finally.”

“What was that?” I asked, curious.

“I finally made love with the son of the Arabs, you know? In the home where I cooked as a girl,” she said. “In my dream last night. It all happened in my dream.”