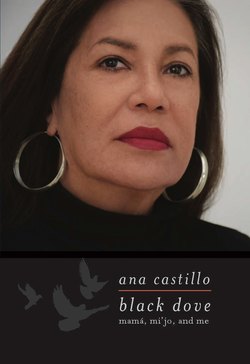

Читать книгу Black Dove - Ana Castillo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFlora, Leonel, and Mamá (Mexico City; approximately 1938).

My Mother’s México

My mother’s México was the brutal urban reality of Luis Buñuel’s Los Olvidados. Children scamming and hustling, fire-eaters, hubcap stealers, Chiclet sellers, miniature accordion players with small, dirty hands stretched out before passersby for a coin, a piece of bread: “Please, señor, for my mother who is very sick.” This was the Mexico City of my family. This was the México from which my mother spared me.

In that Mexico City in the 1930s, Mamá was a street urchin with one ragged dress—but not an orphan, not yet. Because of an unnamed skin disease that covered her whole tiny body with scabs, her head was shaved. At seven years old, or maybe eight, she scurried, quick and invisible as a Mayan messenger, through the throngs of that ancient metropolis in the area known as “La Villita,” where the goddess Guadalupe Tonantzin had made her four divine appearances and ordered el indio Juan Diego four times to tell the Catholic officials to build her a church. “Yes!” and off he went, sure-footed and trembling. Mamá, who was not Mamá but little then, bustled on her own mission toward the corner where her stepfather sold used paperbacks on the curb. At midday he ordered his main meal from a nearby restaurant and ate it out of stainless-steel carryout containers without leaving his place of business. The little girl would take the leftovers and dash them off to her mother, who was lying on a petate—in the one room the whole family shared in a vecindad overflowing with families like their own with all manner of maladies that accompany destitution. Her mother was dying.

María de Jesús Rocha de Castro spent her days and nights in the dark, windowless room reading novels, used paperbacks provided by her new husband from Veracruz, seconds like the food he shared with her. She copied favorite passages and verses into a notebook, which I have inherited, not through the pages of a will but by my mother’s will: she carried the notebook, preserved in its faded newsprint cover, over decades of migration until, one day, it was handed over to me, the daughter who also liked to read, to write, to save things.

María de Jesús named her second daughter after a fictional character, Florinda, but my mother was the eldest daughter. She was not named for romance like my tía Flora—aromatic and evocative—but from the Old Testament, Raquel, a name as impenetrable as the rock in her parents’ shared Guanajuatan family name, Rocha: Raquel Rocha Rocha. And quite a rock my mother was all the days of her life, Moses and Mount Sinai and God striking lightning all over the place, Raquel the Rock.

One day, María de Jesús—the maternal grandmother whom I never knew but was told I am so much like—asked her eldest daughter to purchase a harmonica for her. Of course, it would be a cheap one that could be obtained from a street vendor not unlike her bookselling husband. This the child did, and brought it to her mother’s deathbed, a straw mat on a stone floor. And when the mother felt well enough, she produced music out of the little instrument, in the dark of that one room in Mexico City, the city where she had gone with her parents and two eldest children with the hope of getting good medical care that could rarely be found in those days outside the capital.

Instead, María stood in line outside a dispensary. Dispensaries were medical clinic substitutes, equipped to offer little more than drugs, certain common injections, and lightweight medical advice. In a rosary chain of women like herself—black rebozos, babies at the breast—she waited for hours in the sun or rain, on the ground. So many lives and that woman at the end, there, yes, that one, my mother’s young mother waited, dying.

In the 1970s while I was living alone in Mexico City, I had a medical student friend who took me to such a dispensary where he worked most evenings. The place, located in a poor colonia, consisted of two dark rooms—one for the receptionist and the other for consultation. The dispensary was crammed to the ceiling with boxes of drugs, mostly from the United States, administered freely to patients. I knew almost nothing about medication, but I knew that in the United States we did not have a once-a-month birth control pill, and that belladonna could not be taken without a doctor’s prescription. And yet, drugs such as these were abundant in the dispensary, and my young friend was not a doctor but, in fact, was a failing medical school student, permitted to prescribe at his own discretion.

María de Jesús was newly widowed during her dispensary days, and why she married again so soon (the bookseller) I cannot say, except that she was so sick—and with two children—that shelter and leftovers may have been reason enough. She bore two children quickly from this second marriage, unlike the first, in which, among other differences, it took seven years before the couple had their first child, a son born in Kansas, and two years later a daughter, my mother, born in Nebraska.

My mother often told me my grandfather worked on the railroads as a signalman. This is what brought the Guanajuatan couple to the United States. From this period—the 1920s—I can construct a biography of the couple myself because María de Jesús was very fond of being photographed. She wore fine silks and chiffons and wide-brimmed hats. Her mustached husband with the heavy-lidded eyes telling of his Indian ancestry sported a gold pocket watch. They drove a Studebaker.

After the Stock Market Crash of 1929, Mexican workers in the United States, suddenly jobless, were quickly returned to the other side of the border. My grandparents returned not with severance pay, not with silk dresses nor wool suits, not with the Studebaker—but with tuberculosis. My grandfather died soon after.

When María de Jesús died (not surprisingly, she was not saved by the rudimentary medical treatment she received at dispensaries), her children—two sons, two daughters—were sent out to work to earn their own keep. Where the sons went, I don’t know as much. But I know about the daughters—Raquel and her younger sister, Flora—because when they grew up and became women, they told me in kitchens, over meals, and into late evenings, that by the time they were ten years old, they worked as live-in domestics.

My mother was a little servant. Perhaps that is why later, when she became a wife and mother, she kept a neat home. My tía Flora was sent to the kitchen of an Arab family. And in adulthood, her tiny flat was always crowded, filled with crazy chaos, as she became the best Mexican cook on both sides of the border. It was a veritable Tenochtitlán feast at Flora’s table in her humble casita at the outpost of Mesoamerica—that is to say, the mero corazón of the Mexican barrio of Chicago: spices and sauces of cumin and sesame seeds, chocolate, ground peanuts, and all varieties of chiles; cuisines far from shy or hesitant, but bold and audacious, of fish, fowl, and meats. Feasts fit for a queen.

When my mother was about seventeen, her guardian grandparents decided to take their US-born grandchildren closer to the border. The strategy of the migrating abuelos was that the US-born grandchildren could get better work or, at least, perhaps better pay on the US side. They settled in Nuevo Laredo. One year later, my mother was raped—or at a minimum clearly taken advantage of—by the owner of the restaurant on the US side of the border where she had found work as a waitress. (She never said which it was, or at least, she never told me.) He was married with a family and considerably older than the teenager who bore his son. The best my great-grandfather could do at that point on behalf of my mother’s honor was to get the man to provide for her. He paid the rent on a little one-room wooden house, which, of course, gave him further claims on my mother. Two years later, a daughter was born.

Three years more and Mamá’s México ended as a daily construct of her reality when, with machete in hand, she went out to make her own path. She left her five-year-old son with her sister Flora, who was newlywed (and soon to be widowed), and, with her three-year-old girl, followed some cousins who had gone up north. A year later, she would move to Chicago alone with both children. Mamá remembers all this as the longest year of her life.

In Chicago, my mother went to work in factories. Doña Jovita, the curandera who took care of Mamá’s two children while she worked, convinced the young mother to marry her teenage son. The next summer, I was born. Mamá stayed in factories until the last one closed up and packed off to Southeast Asia, leaving its union workers without work and some without pensions, and sending my mother into early retirement.

Mamá, a dark mestiza, inherited the complexes and fears of the colonized and the strange sense of national pride that permeates the new society of the conquered. Although she lived in Chicago for over forty years, she spoke only Spanish. She threw out English words—zas, zas, zas—like stray bullets leveled at gringos, at grandchildren, at her African American Avon manager.

When I was twelve, I saw Mamá’s Mexico City for the first time. My mother and I traveled from Chicago to Nuevo Laredo by car. It was possibly the hottest place on earth in the month of July. Mamá didn’t have much choice about when to travel, since the first two weeks of July were when the factory where she worked closed down and workers were given vacation time. Mamá paid a young Mexican who was looking for riders to take us to the border. The car broke down, we slept in it at night, we were refused service at gas stations and in restaurants in the South. Finally, we got to my great-grandmother’s two-room wooden house with an outhouse and a shower outside.

I had made friends with the little girl next door, Rosita, on a previous visit to Nuevo Laredo. At that time, we climbed trees and fed the chickens and took sides with each other against her older brother. That’s how and why I learned to write Spanish, to write to my friend. My mother said it was also to exchange letters with Mamá Grande, my mother’s grandmother, but I wanted to keep up with Rosita. My mother, after long days at the factory, would come home to make dinner, and after the dishes and just before bed, she, with her sixth-grade education and admirable penmanship, would sit me down at the kitchen table and teach me how to write in Spanish, phonetically, with soft vowels, with humor, with a pencil, and with no book.

On the next visit, Rosita was fourteen. She had crossed over to that place of no return—breasts and boys. Her dark cheeks were flushed all the time, and in place of the two thick plaits with red ribbons she once wore, she now left her hair loose down her back. She didn’t want to climb trees anymore. I remember a quiet, tentative conversation in the bedroom she shared with her grandmother who had raised her. Not long after that, Rosita ran off—with whom, where, or what became of her life, I was never to know.

In Nuevo Laredo we were met by my tía Flora—who had also traveled from Chicago—with her five children, ranging from ages fourteen to four. The husbands of these two sisters did not come along on this pilgrimage because they were men who, despite having families, were not family men. They passed up their traditional right to accompany their wives and children on the temporary repatriation.

There were too many children to sleep in the house, so we were sent up to the flat roof to sleep under the stars. My mother had not known that she needed permission from my father to take me into México, so with my cousin’s birth certificate to pass me off as Mexican-born, we all got on a train one day, and I illegally entered Mexico City.

Our life in Chicago was not suburban backyards with swings and grassy lawns. It was not what I saw on TV. And yet it was not the degree of poverty in which we all found ourselves immersed overnight, through inheritance, birth, bad luck, or destiny. It was the destiny that my mother and her sister had dodged by doing as their mother, María de Jesús, had done decades before (for a period of her life at least) by getting the hell out of México, however they could. It was destiny in México that my mother’s little brother refused to reject because of his hatred for capitalism, which he felt was embodied by the United States. Leonel came out of the México of Diego and Frida and was a proud communist. Dark and handsome in his youth, with thin lips that curled up, giving him the permanent expression of a cynic, the brother left behind came to get us at the little hotel in Mexico City where my mother’s stepfather, who was still selling books on a street corner, had installed us the night before. He’d met us at the train station, feeding us all bowls of atole for our late meal at the restaurant where his credit was good.

My cousin Sandra and I opened the door for Tío Leonel. We didn’t know who he was. We told him our mothers had gone on an errand, taking the younger children with them. My tío Leonel did not step all the way into the room. We were young females alone, and for him to do so would have been improper. He looked me up and down with black eyes as black as my mother’s, as black as mine, and knitted eyebrows as serious as Mamá’s and as serious as mine were to become.

“You are Raquel’s daughter?” he asked. I nodded. And then he left.

He returned for us later, Mamá and me and my tía Flora and her five children, eight of us all together, plus big suitcases, and took us to his home. Home for Tío Leonel was a dark room in a vecindad. Vecindades are communal living quarters. Families stay in single rooms. They share toilet and water facilities. The women have a tiny closet for a kitchen just outside their family’s room, and they cook on a griddle on the floor. I don’t remember my uncle’s common-law wife’s name. I am almost certain that it was María, but that would be a lucky guess. I remember my cousins who were all younger than me and their cuh-razy chilango accents. But I don’t remember their names or how many there were then. There were nearly ten—but not ten yet—because that would be the total number my uncle and his woman would eventually have. Still, it felt like ten. So now there were four adults and at least thirteen children, age fourteen and under, staying in one room.

We didn’t have to worry about crowding the bathroom because the toilets were already shared by the entire vecindad. There were no lights and no plumbing. At night sometimes my uncle cleverly brought in an electrical line from outside and connected a bulb. This was not always possible or safe. The sinks used for every kind of washing were unsanitary. Sandra and I went to wash our hands and faces one morning and both stepped back at the sight of a very ugly black fish that had burst out of the drainpipe and was swimming around in the large plugged-up basin.

For entertainment, we played balero with our cousins who were experts. Balero was a handheld toy where the object of the game was to flip a wooden ball on a string onto a peg. My little cousins could not afford a real balero, even the cheap kind you find in abundance in colorful mercados, and made their own using cans, found string, and stones or cork.

A neighbor in the vecindad who owned the local candy stand had a black-and-white portable TV. At a certain hour every evening, she charged the children who could afford it to sit in the store to watch their favorite cartoon show.

I was twelve years old, Sandra was thirteen, and her older brother was fourteen. We were beyond cartoon shows and taking balero contests seriously, and we were talking our early teen talk to each other in English. It was 1965 and the Rolling Stones were singing “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” in English over Spanish radio on my cousin’s made-in-Japan transistor, and we insolent US-born adolescents wanted no part of México. Not the México of the amusement park, La Montaña Rusa, where we went one day and had great fun on the roller coaster. Not the México of sleeping under the stars on the roof of my tío Aurelio’s home in Nuevo Laredo. Not the México of the splendid gardens of Chapultepec Park, of the cadet heroes, Los Niños Héroes, who valiantly but fatally fought off the invasion of US troops. We wanted no part of this México, where we all slept on the mattress our mothers had purchased for us on the first night in my tío Leonel’s home. It was laid out in the middle of the room, and six children and two grown women slept on it crossways, lined up neatly like Chinese soldiers on the front line at night in the trenches, head-to-toe, head-to-toe. My tío and his wife and children all slept around us on piles of rags.

We had, with one train ride, stepped right into our mothers’ México, unchanged in the nearly two decades since their departure.

Years later, when I was living on my own in California, I met my family at the appointed meeting place—my tío Aurelio’s in Nuevo Laredo—and traveled south by van with everybody to Mexico City. My tía Flora, this time without any of her children, came along, too. It was 1976, the birthday of the United States, but in México my elders were all dying. The great-grandmother, Apolinar, had died earlier that same year and we had only recently received word of it. The great-uncle and border official, Tío Aurelio, had a heart condition and also died before this visit. My tía Flora’s veracruzano bookselling father had died that year, too. We had only the little brother Leonel to visit. The young anticapitalista—once so proud of his sole possession (a new bicycle, which eventually was stolen), devoted to his family in his own way (although the older children had gone off on their own, while the youngest sold Chiclets on the streets)—was on his deathbed at forty.

Leonel was suffering from a corroded liver, cirrhosis ridden. By then, his lot had improved so that he had two rooms, a real bed, and electricity, but not much more. We stood around his bed and visited awhile so he could meet his brother-in-law and some other members of my mother’s family whom he had never known before.

We went to visit his oldest daughter, around my age, at the house where she worked as a live-in domestic. She could not receive company, of course, but was allowed to visit with us outside for a bit. We dropped in on her older brother, too. He had an honest-to-goodness apartment—three whole rooms and its own kitchen. All grown, he worked in a factory and had a young family of his own.

One evening, my tía Flora and I ran into Leonel on the street, not far from where the cousin with the apartment lived. He was now a yellowish wire of a man and appeared quite drunk, his pants held up by a rope. He glanced at me, and then asked my tía Flora, “Is this Raquel’s daughter?” My tía, in her usual happy-sounding way, said, “Yes, yes, of course she is the hija of Raquel.” And then Tía, who is more veracruzana than chilanga—that is, more palm than granite—laughed a summer-rainstorm laugh.

Of course I was and am the daughter of Raquel. But I was the one born so far north that not only my tío but all my relatives in México found it hard to think me real. The United States was Atlantis—and there was no Atlantis—and therefore having been born there, I could not exist. He nodded at my aunt, who was real, but not at me, who was a hologram, and went on his way.

“My poor brother,” my tía said, “he looks like Cantinflas,” comparing him to the renowned comedic actor, famous for his derelict appearance and street ways. That was the last time we saw him, and by the end of summer, he was dead.

If the double “rock” in Mamá’s name (and the “castle” at the end through marriage) had dubbed her the stoic sister, the flower in Flora’s name perfumed her urban life and warded off the sadness of trying times. And those had been many in my tía’s life, multiplied with the years as her children grew up far from México in Chicago’s poverty.

So it was that night that my tía and I, riding a city bus, jumped off suddenly in a plaza where trios and duos of musicians gathered for hire, and we brought a late-night serenade to Mamá and family at our hotel. That was when my tía Flora and I bonded as big-time dreamers. After the serenade and after Dad (who came on this trip) had brought out a bottle of mezcal and we had all shared a drink with the musicians, Mamá told me some of the stories I share here now.

By migrating, Mamá saved me from the life of a live-in domestic and perhaps from inescapable poverty in Mexico City. But it was the perseverance of Raquel the Rock and the irrepressible sensuality of Flora the thick-stemmed calla lily that saved me, too. “Ana del Aire,” my mother called me (after the popular telenovela of the 1970s). Woman of the air, not earthbound, not rooted to one place—not to México where Mamá’s mother died, not to Chicago where I was born and where my mother passed away on a dialysis machine, not to New Mexico where I made a home for my son and later, alone for myself—but to everywhere at once.

And when the world so big becomes a small windowless room for me, I draw from the vision of María de Jesús. I read and write poems. I listen to music, I sing—with the voice of my ancestors from Guanajuato who had birds in their throats. I paint with my heart, with acrylics and oils on linen and cotton. On the phone, I talk to my son, to a lover, and with my comadres. I tell a story. I make a sound and leave a mark—as palatable as a prickly pear, more solid than stone.