Читать книгу Trapeze - Anais Nin - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

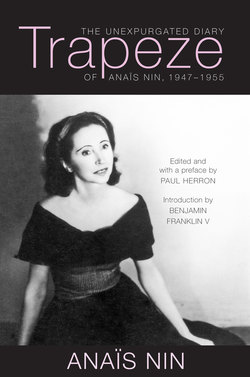

Despite publishing six novels and numerous short stories from the 1930s into the 1960s, Anaïs Nin (1903-1977) failed to gain acceptance as a fiction writer. Yet she became famous in the mid-1960s with the publication of The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1931-1934 and The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1934-1939 (volumes 1 and 2). These books appealed to a wide audience and still please not only because of their attractive authorial persona but also because they record Nin’s involvement in Paris with such memorable, fully drawn individuals as Henry Miller, June Miller, Otto Rank, and a man known only as Gonzalo. With friends less significant and less detailed, with themes less developed, and with an increasing reliance on letters to and from Nin to chronicle her life, the next five volumes of the diary are not so impressive as the initial two.1 All seven diaries leave questions unanswered. In The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1947-1955 (volume 5), for instance, a reader might reasonably wonder why the cosmopolitan Nin, a resident of New York City, also dwelled in Sierra Madre, on the edge of a woods outside Los Angeles. Did she live alone on the two coasts? And then, how could this author whose books did not sell well and who held no job afford to maintain two homes, fly frequently between them, and take occasional trips to Mexico? Covering the same years as The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1947-1955, Trapeze answers these questions while providing a compelling narrative of Nin’s life during this period.

Trapeze is the sixth volume to offer versions of Nin’s life substantially different from those Nin presented in the initial sequence of diaries.2 Described as unexpurgated, these alternative treatments of events resulted from her withholding information from the diaries as originally published, information that would have embarrassed and probably harmed her and certain of her associates. Her death and the deaths of her friends eliminated such concerns. The first revised volume, Henry and June, divulges, among many other things, that Nin had a husband, the banker Hugh Guiler. The name of this man she wed in 1923 and to whom she remained married is absent from all diaries published during her lifetime.3

The year after their marriage Guiler was transferred from New York City to Paris, where the couple lived until 1939 and where he provided funds for his wife to live as an independent woman. As such in the 1930s, Nin devoted herself to literary pursuits and had sexual affairs with some men, including, first and most notably, Henry Miller. Trapeze reveals that Guiler continued supporting her even when, after repatriation, she established a residence in California in the 1940s. There she cohabited with Rupert Pole, a printer and failed actor as well as, later, a forest ranger, which accounts for her presence in Sierra Madre. He was the son of the actor Reginald Pole and stepson of the architect Lloyd Wright (son of Frank Lloyd Wright), his mother’s second husband. These relationships explain why Reginald Pole and the Wrights appear in The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1947-1955, which does not mention Rupert Pole.

Trapeze primarily documents Nin’s lives with and attitudes toward Guiler and Pole. The one mainly provided security; the other, passion. Her feelings for these men were complex. Ambivalent toward them, Nin sometimes even pitied them. Guiler was too stolid and willful for her; he lacked charisma. His personal habits disgusted her. She disapproved of his profession, even though his banking success, which she belittled, enabled her to live as she wished to a large degree. Some of his business decisions upset her, including one to retire before being made a vice president. More than once she stated that she did not love him, yet guilt over being indebted to him and the need of his munificence kept her from divorcing him, despite vowing to end their marriage. When he adopted the name Ian Hugo and entered the art world as engraver and filmmaker, though, she supported him, including by using some of his engravings as illustrations in her books and by appearing in his films. Ultimately, his kindness, generosity, and seemingly limitless love permitted her to have a rewarding physical life with Pole, about which he was then unaware.4

With her ardor for longtime lover Gonzalo Moré dead, with her most recent paramour Bill Pinckard stationed in Korea, with the impossibility of an affair with the desirable but gay Gore Vidal, and with Guiler abroad in Cuba, Nin wanted a lover in early 1947. She found one at a party in New York City. She was smitten with this man, Rupert Pole, to the extent that she soon agreed to motor with him to California in his Ford Model A.5 Thus began a romance that lasted the remainder of her life and that brought her both joy and frustration. The joy was sex; the frustration was almost everything else. Not only was his family insufferable at times, but his fault finding, temper, frugality, pettiness, and bourgeois values irritated her; his wandering eye distressed her. As an amateur guitarist and violist he was somewhat artistic, but was otherwise shallow. His job requirements dictated that he live among forest rangers, people she considered mediocre. She anesthetized herself against unpleasantness with Martinis and occasional visits to Acapulco. In other words, her lives with Guiler and Pole were less than ideal, even maddening, but because they both provided something she needed, she endured their shortcomings. This acceptingness is perhaps most obvious in her agreeing to marry Pole. Becoming his wife made her a bigamist. With each man she lived half a life.

Nin had numerous friends who assisted her to one degree or another during the years covered in Trapeze. They include author and editor Gore Vidal; Jim Herlihy, writer and her spiritual child; critic Maxwell Geismar and his wife, Anne; Louis and Bebe Barron, early composers of electronic music; and bookstore owner Lawrence Maxwell. She relied on doctors, especially the analysts Clement Staff and Inge Bogner, with whom she discussed issues relating to her double life, but also Max Jacobson, whose medications energized her. He was later known as Dr. Feelgood for giving his patients amphetamines. In writing about some of these people she reveals a trait she describes as a character flaw: intolerance of others’ deficiencies. For example, Herlihy was one of her greatest supporters, serving as a refuge from her travails with Guiler and Pole and living with Guiler when he, her husband, needed help while she was in California. Appreciative of his numerous services, Nin nonetheless thought him childish, believed he should have done more for Guiler, and disapproved of his writing, which she considered banal.

While living alternately with Guiler and Pole, Nin continued writing. Though she had some literary success, by the mid-1950s she was dispirited. Until the mid-1940s her books had been published only by small firms, including her own Gemor Press. Things changed when Gore Vidal, an editor at E. P. Dutton, arranged for his company to publish three of her books in consecutive years, beginning in 1946. They were the novels Ladders to Fire and Children of the Albatross, plus Under a Glass Bell, a collection of stories enlarged from earlier editions. She was disappointed when Dutton rejected The Four-Chambered Heart, a novel Duell, Sloan and Pearce published in 1950. The next novel, A Spy in the House of Love, caused problems that led to her considering herself a literary failure. Written in Sierra Madre and completed in June 1950, it did not attract a publisher, mainly, according to Nin, because the character known as the lie detector was too amorphous and the story was too much a fantasy. After the manuscript was rejected many times, she rewrote it, retaining the lie detector but reducing or eliminating the fantastical elements in order to make it more understandable. Additional rejections followed. Finally, British Book Centre agreed to publish it if Nin paid the company’s costs, which Guiler did, though the firm’s financial difficulties and distribution issues delayed publication. When the novel appeared in 1954, it sold poorly, generating less than $200 in royalties. Despite feeling defeated in the literary marketplace, Nin retained a belief in her artistry, going so far as to consider herself the equal of Djuna Barnes, Anna Kavan, and Virginia Woolf as a force in what she considered new writing.

The revelations in Trapeze make understandable the fragmentary, relatively undeveloped nature of The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1947-1955. When preparing the earlier book for publication, Nin could not include the most important events in her life, which revolved around Guiler and Pole, because she was not at liberty to identify these men.6 In that volume she presents herself as free, as a woman confronting life on her own without romantic attachment or financial support. In detailing her lives with Guiler and Pole and the emotional toll these relationships took on her, Trapeze sets the record straight.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN V

University of South Carolina

August 2015

Notes

1. The first series of diaries consists of The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1931-1934 (1966); The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1934-1939 (1967); The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1939-1944 (1969); The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1944-1947 (1971); The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1947-1955 (1974); The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1955-1966 (1976); and The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1966-1974 (1980). Gunther Stuhlmann, Nin’s agent, edited and introduced all of them. Paperbacks of these titles number them sequentially, from volume 1 to volume 7.

2. This later series of diaries consists of Henry and June (1986), Incest (1992), Fire (1995), Nearer the Moon (1996), and Mirages (2013). Rupert Pole, executor of the Anaïs Nin Trust, wrote prefatory material for the first four of these books. John Ferrone, Nin’s editor at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, edited the initial volume; under Pole’s supervision, Gunther Stuhlmann edited the next three diaries. Paul Herron edited and Kim Krizan introduced Mirages.

3. Guiler is also not mentioned in two volumes published posthumously, Linotte: The Early Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1914-1920 (1978), which concludes before Nin met him, and The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1966-1974. First as beau and then as husband, he figures prominently in books that recount her life from 1920 to 1931 and that, with Linotte, constitute another grouping of her diaries: The Early Diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume Two, 1920-1923 (1982); The Early Diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume Three, 1923-1927 (1983); and The Early Diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume Four, 1927-1931 (1985). Joaquín Nin-Culmell, Nin’s brother, introduced all four of the early diaries. John Ferrone edited Linotte; Rupert Pole edited the other volumes.

4. Guiler knew of his wife’s bond with Pole by the mid-1960s. In a letter to Pole dated 23 February 1977, he states that for more than a decade he has known of Pole’s “special relationship with Anaïs” (“Rupert Pole and Hugh Guiler: An Unlikely Partnership,” A Café in Space: The Anaïs Nin Literary Journal 8 [2011]: 18).

5. The original published version of Nin’s decision to make the trip reads: “I found a friend who was driving to Las Vegas to get a divorce, and we agreed to share expenses,” with the name and sex of the companion unspecified (The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1944-1947 [New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971], 197).

6. Though Nin mentions the art of Ian Hugo (Hugh Guiler) in the initial series of diaries, including The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1947-1955, she implies that her relationship with him is strictly professional.