Читать книгу Trapeze - Anais Nin - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPART TWO OF MY LIFE

1947

NEW YORK, MARCH 1947

I was recovering from all the deep wounds of Bill Pinckard’s absence, of Gore Vidal’s unattainableness, of the disintegration of my love for Gonzalo. Hugo was away in Cuba, and I was going out with Bernard Pfriem, a vital, charming man who desired me but whom I did not desire. Hazel McKinley is a burlesque queen in private life who literally strips herself bare at her parties, and then the next day she informs all her friends of the previous night’s doings over the telephone. Hazel is blonde, very fat, weighing at least 200 pounds, a painter of childish watercolors proclaiming her age to be all of thirteen, an insatiable nymphomaniac who is always starved for men because they rarely stay more than one night. She telephoned me: “Oh Anaïs, bring me some men. I’m having a little party, and I haven’t any men I could be interested in! Please, Anaïs.”

I, thinking that she would attack Bernard and keep him there, agreed to come.

When I arrived at the hotel, I was ushered into an elevator with a tremendously tall young man. As I saw his handsome face, I said to myself: Caution. Danger. He is probably homosexual.

His name was Rupert Pole.

In Hazel’s room, he and I stood talking for a moment. Rupert spoke first, having heard I was Spanish. Ordinary remarks. We discussed Schoenberg whom he had met in Hollywood. He intimated his belief in pacifism and mystical studies.

Later we found ourselves on the couch with his friend from California. I was on my guard with Rupert. But somehow or other we talked about printing (he excused himself for the condition of his hands) and that created a bond. I told him I had printed my books; he told me he was printing Christmas cards to earn a living. I told him I was a writer; he told me he was an actor out of work.

He was born in Hollywood.

He is twenty-eight.

His mother is re-married, this time to the son of Frank Lloyd Wright.

His father is a writer.

I remember that as we talked, we plunged deep, deep eyes into each other.

Then people intervened.

The homosexual is passive, so I was surprised when Rupert came up to me when I was ready to leave (early because Bernard was frightened by Hazel’s advances and wanted to make love to me) and said, “I would like to see you again.”

Hazel told me afterward, “He asked about you. He was interested in you.”

That night while Bernard made love to me, it was Rupert’s face that hung before my eyes.

Later Rupert called me. Hugo was away in Cuba. I invited him for dinner. I lit all the candles I had placed on the Spanish feast table. He took charge of the dinner. I sat far from him on the couch. We did not talk very long. His eyes were wet and glistening, and he was hungry for caresses. The radio was playing the love scene of Tristan and Isolde. We stood up. My mood was, above all, amazement—to see this beautiful, incredible face over mine, and to find in this slender, dreamy, remote young man a burst of electric passion.

The second surprise was that I, who never responded the first time in any love affair, responded to Rupert. He was so vehement, lyrical, passionate, and electric. His arms were strong. He pressed his body against mine as if he wanted to penetrate it from head to foot. He churned, thrashing sensually as if he would make love once and forever, with his whole force. The candles burned away. Tristan and Isolde sang sadly. But Rupert and I twice were shaken by such tremors of desire and pleasure that I thought we would die, like people who touched a third rail in the subway tunnel.

He stayed on. We talked. We made sandwiches. We fell asleep on my small bed. In the morning he was amazed by the painted window, like a pagan church of festive colors. I wore a white kimono. It was snowing. I made breakfast. I was expected at Thurema Sokol’s, and he was driving to the country for the weekend at a friend’s house. When I went downstairs with him, I was introduced to Cleo, his Ford Model A. Rupert dropped me off at Thurema’s, said something lyrical, poetic, and drove off, leaving the light of his sea eyes to illumine the day. I went to see Thurema in a high state of exaltation. This was more than Bill. It was Bill handsomer, warmer, older, full of passion and love.

Would it only last one night? I asked myself, no longer able to believe in happiness.

He disappeared for several days. He had an infected finger. He was entangled with an ex-wife and a mistress he did not love.

Hugo returned.

Hugo was out for the evening when Rupert came with his guitar and sang. At midnight I had to send him away. I went to see him at his printing press. Rupert, so unique in appearance, so poetic, so aristocratic, seemed incongruous printing trite Christmas cards designed by his friend Eyvind Earle. That day I intended to stay an hour. I had an important dinner engagement arranged by Tana de Gamez at some celebrity’s house with Hugo there. But when I called Tana and said, “Te veo más tarde,” Rupert said no, I was having dinner with him. So I invented some absurd story for Tana, freed myself and went off with Rupert in Cleo. This time he took me to his shabby and unkempt little apartment. He kicked his soiled clothes into the closet, blushed for the disorder, but all I minded was the bare, glaring electric bulbs. The lovemaking was less intense. It may have been my mood. He gave me his kimono to wear and a bad metaphysical book he admired.

Our next encounter was at the Bibbiena Spanish restaurant on 14th Street. Rupert said in the middle of dinner, “I am driving back to Los Angeles soon. You once said you wanted to go to Mexico. Why don’t you drive with me to Los Angeles and then go on with your trip from there?”

“Yes, why not?” I said.

Later, Rupert came with his arms full of maps and wearing a white scarf. The white scarf (the first was worn by Bill Pinckard) was for me a continuation of the broken experience with Bill. I watched Rupert’s short, boyish hands pointing to the map. He was planning our trip. It was for my sake that Rupert would not take the shortest way—through the Middle West—because it is a dull way. He chose a southwest route and began to plan what he would show me.

Aside from our marvelous nights, what most attracted me was our harmony of rhythm. We got dressed at equal speed; we packed quickly. We leaped into the car; all our responses and reflexes were swift. There was a great elation in this for me, after living with Hugo’s slow, laborious rhythm.

His voice over the telephone is clear like a perfect bell. Some deep part of his being is unknown to him, protected by this manly heartiness.

I am happy.

“Does it make you happy to know you have brought me back to life?” I asked.

“You seemed very alive to me.”

“But sad.”

“Yes, sad. But I shall make you happier still. I have our trip all planned.”

To Dr. Clement Staff: “I fear my inadequate physical endurance. But now I know all these are fears of leaving.”

Staff: “When you are happy you are relaxed and you do not get ill; these are anxieties.”

The causes of anxiety are removed: I have not set myself to possess Rupert, win him, keep him! I have not strained after an illusion. I have been simple and truthful. My anxieties, fear of loss, are less than before; they do not strangle me as they did before.

Oh to win, to win freedom, enjoyment.

Looking back on my relationships, I feel I live in a ghostly world of shadows, of feebleness.

In Rupert there is enough physical resemblance to Bill Pinckard that I feel I am continuing my love for Bill, that I do not feel I am deserting Bill. A more hot-blooded Bill he is, a Bill ten years older.

Or will Bill always be passive and fearful?

Rupert is capable. He takes over the cooking, expertly. He repairs his own car. He does not ask as Gonzalo does: “Where is the knife? Where is the salt?”

I bought, for Rupert, my first pair of slacks.

Gonzalo comes every day. We kiss on the cheeks. He looks like a tired old lion. He works at the Press, at home. I get him printing jobs. I gave him a story, and House of Incest to do. Very little money.

MARCH 30, 1947

When I went to Hazel’s last night and met Guy Blake, a handsome young actor I had seen there before, I felt immune, unresponsive. To escape a loud movie director’s monologue, Hazel and I went into her bedroom to talk, closing the door. Blake entered. Slim, dark-haired, blue-eyed, with a lovely voice. Hazel had said, “He does not like women,” so I was not on my guard. He asked her to leave us. She closed the door. He began to kiss me and I to resist. I resisted because I knew that he knew Rupert, that Hazel would know and Rupert might hear of it. I wanted so much to be faithful, and above all not to endanger my relationship with Rupert. So I resisted. And it was difficult, because he was beautiful, ardent and violent.

As I tried to move away from his kiss, he pushed me onto the bed and lay over me. He was so violent. He took my hair into his hands and pulled it to keep my mouth welded to his.

“No, no, no, no—I want to be faithful to someone,” I said. “No, no, no, no.”

And got up.

“Let me walk you home!”

“But I have a husband. He is home, waiting.”

“It’s Rupert, isn’t it?”

“I can’t say.”

“I know it’s Rupert.”

“I can’t say.”

He was disconcerted by my resistance. He went back to the party. I repainted my lips.

Then he walked me home.

“Let’s stop for a drink.”

“No, it’s late.”

But he was willful.

We sat at the back of a bar. He said, “Will you come to my room one night?”

“No.”

“Why?”

“I told you why.”

“Oh, women! I want you to come.”

“I’ll spend an evening with you.”

“Oh, no, a whole night, or nothing at all. A night and a day. I want to know you. I never cared about Hazel; it would only be physical. With you . . .”

He was like a hypnotist, using all his assertiveness. His hand under my dress. Or pulling my hair again. At times I could not keep answering his kiss. The ardor, the fervor affected me. If only he had not known Rupert. With his fingers he knew I was not unresponsive. I liked his violence. He bit me.

“Come with me tonight. I want you.”

“No, no, no.”

We walked home.

Any other time I would have yielded. But I would not risk the loss of Rupert. (Who said Rupert expected faithfulness? I want to give it to him.) Blake had said, “Rupert is a nice fellow, but a dreamer.”

A dreamer . . .

At the door he kissed me again and then held me wildly, violently. I fought to move away, but the more I fought the harder he clutched me, and this clutching aroused me; now and then I would rub against him as he rubbed against me, then tear myself away. Then he held me in such frenzy that he came, and I was still; I was unable to pull away in the middle of this frenzy.

To free myself I promised another night. Yes, I would come. He affected me sensually.

He was the first seductive man I ever resisted. I took pleasure in resisting; I was angry at his sensual power, at the way his violence aroused me. At one moment the way he pulled my hair to be able to kiss me reminded me of how I once twisted the reins on my horse when he started to run away, the bit pulled sideways to hurt him.

But what most affected me was that since the sensual barriers were removed in me how obvious it is that I could always have had this marvelous violence instead of seeking it from sickly boys, from Gore Vidal or Bill Burford or Lanny Baldwin, Marshall Barer . . .

My instinct now draws or seeks the violent lovers. What a mysterious pattern. If I had not known Rupert and felt tied to him, Blake would have delighted me. But Rupert is the dreamer—Rupert. Rupert.

Gore still has the power to melt me. It is no longer erotic, but this power to dissolve me with compassion melts my whole body so that still, if he chose to take me, I would be happy. He gives me his softness, his sickness. At the sight of his face my heart is won each time. He puts on his glasses and acts like a senator, watching my love-life as my brother Joaquín did, with a sad resignation, asking me to marry him, to bear his child by “artificial insemination.” He says when no one else wants me he will still love me.

But now I can keep them separate—even if Gore melts me, I can leave him and dream of Rupert. Violence and life with Rupert. Tenderness with Gore.

Last night Bill Burford took me out. We made our peace, exchanged confessions. At the door I kissed him tenderly, disregarding the deforming mirror of his neurosis, listening to and trusting only my own impulses.

It is the confusion of relationships that causes the misery, seeking to make them what they are not.

Everything is clear now.

I could be completely happy now if I had money to send Gonzalo to France, to travel, to dress, to make myself more beautiful.

Hugo is still completely in love with me.

All I ask is passion with Rupert—romance—a dream.

APRIL 3, 1947

A dream, I said. I prayed for a dream.

Rupert returned from the weekend and called me Monday night (I had shut off the phone during a dinner for Richard Wright and Albert Mangones). He called me Tuesday; I was out (as I hadn’t heard from him during the day, I tried not to think of him). Then last night he said, “I have been reading the stories from Under a Glass Bell. Oh, my darling, what beautiful writing. I felt I was living everything. I could smell the houseboat. And the language—I have never read writing like this. I used to read with my intellect. Those words about the crystal chandelier like blue icicles, I read them slowly.”

I felt such happiness.

I had been so careful not to overwhelm him, not to reveal the stature of my work, to let him discover me slowly, by himself.

MIDNIGHT

We cook dinner together. He assumes leadership. He is planning our trip. He speaks humanly, and not callously (as Bill Pinckard did), of our “relationship.” It may be the only trip we will have together. It must be wonderful. He likes the heat and the South, so we’re going to New Orleans, which he has never seen. Slowly the trip becomes more wonderful.

Afterwards, during a stormy, nervous, wiry, electric lovemaking—so harmonious, virile, violent, without sadism (he does not need to bite or to hurt to feel lusty and strong), he said, “If it’s like this in this cold city, my God, what will it be in the heat, in the sun, on the beach? What will happen to us?”

“Our bodies understand each other.”

He talks of how his father will like me.

It all harmonizes—our primitive life—orchestrates into pleasure.

My only fear is my endurance! (Bad food, strain, all the hardships of casual traveling.)

But I must remember—Anaïs, remember—this relationship is not forever. Do not seek it forever. His choice of vocation, forestry, will take him to Colorado: “I want to do something simple, work with my hands, take root.” Or will his love of acting take him to Hollywood? (He has already had a screen test.)

But I am happy. I do not have anxiety or the need for reassurance. I live in the present at last.

I feel great tenderness for Hugo, a grateful tenderness.

I feel altogether grateful; Rupert complains that on screen he looked too young, that his appeal was too boyish, not manly. He is a strange mixture. It is true that he looks younger than twenty-eight (alas!), yet in many ways he behaves more maturely than most men I have known.

It is his extreme slenderness and lankiness that give him the appearance of a boy at times. He is so tall, as tall as Hugo or Gonzalo, but weighs half, certainly. Then his neck is so slender, long.

It is in his hands that lies the great difference.

All the hands I have loved (except Gonzalo’s) were aesthetic hands, especially Pinckard’s, slender, white, fragile, soft-skinned.

Rupert’s hands are sensitive but ruddy, roughened by activity—firm, not childish.

After lovemaking he said, “We are like two electrically charged magnets; when we touch it sets off a terrific light and fire; when we separate we die.”

I will not say, “Come with me to Mexico.” But that is what I want. He has just enough money for the trip to Hollywood, where his mother is, where he will look for a job.

I feel impelled not to clutch, not to seek words of permanence, as I did before. Perhaps if I could have behaved like this with Bill Pinckard my relationship with him might have been better.

At the first sign of jealousy I think: Anaïs, have faith. Have faith in the way he takes you.

It is wonderful, the erotic excitement into which he pours the elements of his nature: swiftness, lightning, mercury, a string instrumentalist’s fingers.

More electricity than with Albert.

He does not like slacks! I had bought my first slacks as a concession to his Americanism, thinking them inevitable on a trip. But he likes femininity.

When we kiss with our eyes closed I like to open mine and see his long-lashed ones closed in the utter druggedness of desire.

When I lie on the couch, and he swoops down on me, then his eyes are open.

A penis has all the characteristics of its owner. There are lazy penises, like Gonzalo’s; there are leaping, frigid ones; there are piercing and stabbing ones. When inside the womb they act so differently!

Rupert’s is slender, active, leaping, wiry. He teases me into a frenzy before, by kisses, by caresses, by his hands, by friction, by undulations of the body.

I feel that Rupert and I connect electrically on a subterranean level; he is not aware of it as I am.

He was born February 18, 1919 at three in the morning in Los Angeles, and I feel superstitious about this. He has the love of the sea.

He comes to activate me.

Two trends conflict in him: he wants security, roots, wife, children, but he wants adventure and freedom. His desire for children is very strong.

Home is important. “I want music, and you can’t have music without stability.”

Oh, mon journal, Anaïs, the love-starved child, is fulfilled in a plenitude of love.

I open my eyes to reach for a letter from Bill Pinckard, a love-letter, dreaming of photographing me naked, of our going to Paris alone together: “You are so wonderful in every way.”

Then I weep desperately once more over the death of my love for Gonzalo, and though we both know the passion is dead, he can’t weep; he can only deceive himself as he has always done.

“It will all heal up . . . it will heal.”

“No, no, we are separated,” I shout. “It is over, I am going away. I don’t want to see the death, the utter death of the love! I won’t ever return to the hell you made with your violence and doubts.”

He feels old, worn; he has no desire at all for anyone. He embraces me fraternally; it is unbearably sad. He seeks to destroy me with criticism. I am weakened by the past and have pity for Gonzalo left in Helba’s prison.

And the other night Gore repeated: “Marry me, marry me, marry me. I will lock you up in Guatemala and allow you only clay pigeons” (casual lovers). He looked at me adoringly, and when he is there I feel only his presence. I want to enfold him inside my womb, warm him, nourish him.

Today at four, Carter Harman came to work on making House of Incest into an opera. For the first time I see him alone. We work so well, understanding each other and creating together, recreating House of Incest. It fills him with music.

Towards the end, in the twilight, I start to tell him about my marriage because I know he will hear about my life sooner or later. “I want you to know the truth because you are fond of Hugo. I am not betraying Hugo. I am not in love with him; I tried to preserve the marriage, but it’s not a marriage. I don’t seek justification; perhaps I would have had other loves anyway. I don’t know.”

I did not want to lie about my trip. I told him the truth. As I did this I thought I was preventing or dissolving the emotion we have, which I have always sensed in him. I thought I was destroying the feeling that should not be allowed since his marriage is good.

But then I saw he was disturbed and saddened. I said, “You seem sad. Are you worried about Hugo?”

“Oh, no, Anaïs.”

We faced each other. He was leaving. We moved closer: “I’m so fond of you,” he said. “I don’t want you unhappy.” We looked at each other: “I’m so . . . attracted to you.”

“I, too . . . I feel so close.”

Faces drawing nearer.

“Kiss me once, Carter.”

He kissed me with passion.

Once.

At the door he paused.

Incoherent words: “Two years ago we could have been so happy together, Anaïs.”

“But now you’re happily married to Nancy.”

“Yes.”

“I love to work with you, Carter.”

“I love to work with you. Let’s be close friends.”

“Yes, yes.”

He was gentle.

It was I who asked him to kiss me.

He is gentle . . . gentle.

He is not as good for me as Rupert, but he affects me emotionally, deeply.

Oh, Anaïs . . .

That was Monday.

Then Tuesday he came again.

It is hard to work—the air is charged with desire. We sit on the couch. I write down what we agree on. He lies near. When he is too near, I tremble inwardly. I want violence. I feel his turmoil.

Again we talked. He told me: “Before my marriage I was in the army; I was so lonely. What I most wanted when I returned was to be married. Now, after two years, this is the first time I have been tempted. You are dangerous for me. I am afraid that someday I will have to live as you do. But now I couldn’t.”

“I know. That is why I’m leaving New York.”

At the door he says, “Aren’t you going to kiss me?”

Then we kiss longer. He is not violent, but sensual in a melting way. It is not electricity, but a flowing together that is piercingly sweet.

When he leaves, I feel lost.

This is not at all the way I feel with Rupert. With Carter I feel this sickness, this hauntingness. I’m afraid because Carter has the intense blue eyes of Bill (Rupert has eyes like mine, chameleon, now gold, now green, now blue, now grey), the fair skin. My desire for him is like my desire for Bill. I feel dissolved. It is painful.

That evening Carter, Nancy, Hugo and I went out together to see Lincoln Kirstein of the Ballet Society.

I felt depressed. I longed for Rupert to come and rescue me. The next day he came and kissed me but did not take me. Instead he drove me out to the East River to contemplate a red birch tree. It had a beautiful bark the color and texture of a chestnut. I tried to invest this one tree with all possible symbolizations: the tree of life, manly, not a tree of genealogy, but the mystical tree in Hindu mythology occupied by gods and dancers. This was the tree Rupert wanted to protect from devastation, fire, lumberjacks, the tree he wanted to help reproduce, nourish, house, shade.

He says, “Cleo is our houseboat.”

He returns home with me. I dress for a formal dinner and he drives me to Peter Wreden’s house on Park Avenue. He says, “You look pure and Grecian, all in white.” Mariposa blanca, Princesita.

But he was annoyed by my preface to Tropic of Cancer and horrified by the book itself.

He is volatile.

I fought the anxiety I felt at his not making love. Anaïs, Anaïs. Confiance. On the East River he kissed me. He noticed I had no gloves. He wanted me to wear his. He asked: “Are you cold? Do you like my driving?” He took one of my photographs of me: “In this one your eyes are like jewels, and your mouth I love.”

I love . . .

“To live like this,” I said, “to dare to live without knowledge of tomorrow.”

But Anaïs has angoisse, angoisse. I still add up the kisses, I still register the words; I fear it is all unreal. I do not believe.

At the Wredens’, homeliness, comfort, bourgeois solidity. I am bored. Gore is there. He takes me home, and in the taxi we hold hands, or rather I take his hands and nestle them. I rest my head on his shoulder. He kisses me as warmly as one can kiss without sex.

I am lost in three loves (Rupert, Carter, Gore) that are orchestrations of my love and desire for Bill Pinckard.

Sad today.

But I am shopping and delighting in new cotton dresses.

Carter is twenty-eight. He is not tall; he is my height. He has light brown hair. He is very slender. Blond-skinned. His face has great beauty, emotion. He has large, very blue, very brilliant eyes, a bird’s profile, a rich, full mouth. He has an irresistible grin. When he is not smiling fully he looks sad. Above all, he looks sensitive and frail. Yet he went to India during the war, flew a helicopter.

I don’t know if it is my obsession with Bill or reality, but Carter has, as I imagine, physical traits like Bill’s.

But why, why do I have with him this drugged state, fever, illness of love?

Rupert awakens wildness.

Carter comes humbly, almost, with his score in a valise, the metronome.

He and Nancy have music in common. She plays the piano and can copy music for him. Now I wish I had studied with my father. Why did I have this obstinate refusal to study music with my father?

The subtle, the sad, the terrible thing that happens in my life with Hugo. I cannot describe it clearly, only in terms of climate. As soon as he returned from Cuba I felt it. I feel I lose the sun. I feel the climate change to heaviness, greyness, death. I hear his voice. So many times he is like a zombie. He is absent; he is almost invariably depressed.

His analyst speaks of an old childhood sulkiness, resentment. He is full of negative reactions: forgetfulness, absent-mindedness, automatism in talking.

He behaves like an old man. After dinner he falls asleep. Saturdays he wants to sleep. Sundays too. I feel my life clogged, slowed down. I feel oppressed by his face, the solemnity of it. His conversation all factual, his constant budgeting, his total absence of playfulness.

At fifty, he moves slowly, deliberately, without buoyancy. Never has a quick reflex. Our rhythm is discordant. He goes to sleep early, and then at dawn he awakens and reads.

I feel caged, trapped, weighed down. All his good qualities cannot balance this climate in which I cannot live.

Even when I give him my individual attention and we spend an evening together—we went to Chinatown last night—he has pleasure in terms of taking me down in a taxi, but nothing comes out of him to illuminate the evening.

Poor Hugo.

I miss Rupert. I want him to possess me this minute, to keep me. It is only the fears I have that keep me unstable, escaping towards Carter because I feel that Rupert is not for me.

I feel the attraction between Rupert and me is unconscious. He is not fully aware of it as I am now.

APRIL 15, 1947

Staff fights the anxiety. Anxiety is dispersing, splitting the loves. Anxiety because Rupert is the adventure I want, and I fear the instability of it, the unknown.

Staff points out the fears: my own duality between security and freedom—Hugo and Rupert.

When Hugo is absent I feel I could live without him. When he returns the dependency begins again.

After talking with Staff about my fear of giving to Rupert because there is no permanency, I flow again. And when Rupert came I was exuberant and joyous. He always responds to this. I tease him. I say I am going to spend our trip investigating whether he is taking up the study of trees because he loves them or because people have hurt him.

We sit on the couch, and again he becomes the burning lover, his tongue possessing my ear, his mouth on my mouth . . .

Oh, my diary, I am out of hell, I have known happiness.

Our lovemaking is all I want. He has my temperament. He teases me with caresses so much that I have to beg him: “Oh take me, take me!” His slender, slender body pushes against mine; he touches every nook, every curve. We fit so close—lean and pliable. Something is so exciting and tantalizing in him that I get into a frenzy. His quickness, alertness, volatile quality, his constant moving, his flying about in his car all enter into his lovemaking.

The complete frenzy. And then he stayed inside me. He lay over me, and after a moment he began again.

Then he fell asleep, laying his full length over me. And when he awakened he said, “I thought I was far from you, and now I find myself in your arms; it’s so beautiful.”

After violent sensuality, tenderness, more kisses, full and sensual.

Then we go out to shop, and he cooks the dinner as I do, in ten minutes, and enjoys it. And after dinner he lies over me again, at rest, tender, relaxed. A full, complete cycle.

And I am relaxed, natural. I feel the plentitude, the sweetness, the warmth of love. I am happy. We can talk together. We can enjoy together.

Now he is impatient to leave.

Such a being: so well balanced, a poet, mystic, musician, sensualist. He can win me, keep me, hold me if he wants to. He could stop all these flights and divisions. He is more dynamic than Carter.

I love his activity, his kindness.

Whenever he comes, because I think about his fiery intensity, I am surprised to see him slender, delicate; one expects a very big man.

I am happy, happy.

APRIL 20, 1947

Then, after this merging, Rupert vanishes for a few days. Goes here and there, sees his ex-wife, his young girl, does not call, does not say when we will meet again, volatizes, and I feel anxiety. About the girl, Martha, he had said, “I cannot consider her seriously. She is too young, confused, under her mother’s domination, a Christian Scientist, rich and spoiled. You say I’m in love with her? I don’t know. There is no physical attraction. I think of her as a friend. I would have liked her to bear my children.”

(That is how I used to write about Hugo!)

His need of stability—I am his passion. He probably does not feel sure of me.

Anxiety.

And the next day Carter came.

Now Carter I trust. Carter, I feel, loves me deeply. He telephones, he is there. With him, even though he belongs to Nancy, I feel that we are bound, that he will remain close, that he needs and wants continuity. No leaps, no vanishings, no elusiveness.

As does Gore, he settles within me, he nestles, he flows.

I said, “When Hugo and I first came to your house I felt an affinity, a closeness. We talked so easily.”

The desire grows. We work together, awaiting the kiss at the end. The moment our bodies touch I feel his desire aroused. Intoxication. Drunkenness.

We separate.

It hurts.

He fears a split of his being, expansion, and I know all the pain this causes.

Then that same evening I received five yards of luxuriant, fire-red brocade from Bill in Korea wrapped around a secret box, which must have been sent before he received Children of the Albatross, in which I mention such a secret Chinese box as an image of his character. This came to me as an omen: he will like my writing. It will not separate us (I have been anxious). And the next morning I received his letter:

“Cherie, reading the book and comprehending what lay beneath it made me understand you and love you even more. With my heart I say those words. My heart was deeply moved throughout the book.”

Happiness . . . happiness . . . happiness . . . Fullness . . . fullness . . . fullness . . . richness . . .

I knew what Carter felt, but I knew it more by his keenness to see me when Nancy, fearing me, began to withdraw from him. Vibration . . . vibration . . . So sad. I know I bring sadness, conflict to Carter, and yet I know too that I can unleash great music in him, that I am necessary to his growth, that his childish marriage is not enough, that I arouse, shake, stir him to greater things. I know the music in me and my words fire him. I know I am for him what Henry and June Miller were for me, who took me out of a small world into a vaster, more terrible and more magnificent realm.

Oh, Carter, the human treacheries for the sake of greater evolutions. Touching me is another Carter who could not be born out of Nancy—a deeper and wilder Carter—born today.

Last night I had a small farewell party for me. I invited Nancy and Carter. Carter came alone. The cell of the dream makes everything wonderful, transfigured.

I want to dance with him because it means holding him and melting together. This melting together, melting.

Oh Rupert, why don’t you stay close? He has these airy spaces he leaps into. In his little car, he is far away. Cold Springs. Mount Kisko. His ex-wife Janie Lloyd Jones and Martha and friends I don’t know.

Because Carter is faithful to Nancy I trust him, because I know he is caught not by a whim, a casual fantasy, but a deep feeling.

Once I wove a vast fire out of Henry and Gonzalo. Now, again, I feel a vast love encompassing very similar men, stemming from the source of Bill Pinckard.

Oh, Rupert, take all of me, hold me, hold me, hold me. I said to you wildly in the middle of possession: “I belong to you,” and you tightened your grip exultantly, proudly. You too are afraid now?

You said, “We create our own sea!”

PART TWO OF MY LIFE

I feel loved

I feel united with the world

I feel free

Last night at the party I felt beloved.

Pablo said, “Oh, Anaïs, I’m jealous—I feel terribly jealous that someone is taking you away.”

Woody Parrish-Martin, Stanley Haggart . . .

“I will miss you.”

Friends, warm, devoted.

It took me years to conquer hell, to gain faith and peace.

My body is blooming.

I do not feel responsibility for others. I have not made Hugo’s gloom or Gonzalo’s prison. In fact, I fought too long to lighten Hugo and to free Gonzalo.

Friday night both Hugo and I were drained, exhausted. Hugo made dinner solemnly, and sat stagnant. I, equally tired, become more acutely humorous, bubbling, for visitors. I told Hugo I am traveling with Thurema.

NEW YORK, APRIL 23, 1947

Last entry before the trip. Now the diary goes into the vault. On Monday I leave with Rupert. Staff said my anxiety that this trip should not happen is a projection of my own guilt at deserting Hugo, Gore, Gonzalo, Carter, all my friends. The guilt is a myth, he warned. The only traces left of the old illness are anxiety, fear of catastrophe, of pain, of tragedy.

I became tense, tense again.

Suddenly there is no time for all my relationships. No time to see Albert, no time for Edward Graeffe (Chinchilito), no time for Guy Blake pleading over the telephone. One visit from Richard Wright and he falls in love with me and calls me today and says, “Come to France with me.”

Henry Miller writes that he awaits my visit impatiently.

Carter: I keep time for him. We work together. But oh, the sweet torment, the sweet torment. The way he lies on the couch. I realize he is not good for me; he is not violent enough. He is gentle, yielding. He is not daring. He wants the kiss, but I have to lead. It is not good.

It is I who must act.

He responds. I am afraid to lose my control. I want him so much. His mouth, his eyes, his beautiful expression.

He is too quiet for me. But I could be at peace with him. It would be gentle.

My fiery one is absent. Dashed to the country. Darts here and there.

Staff said, “When the anxiety catches you, lie down and think of the analysis. Know you create the myth, the fiction. It is not reality. You are constantly deserting Rupert in your mind because you are afraid to give yourself.”

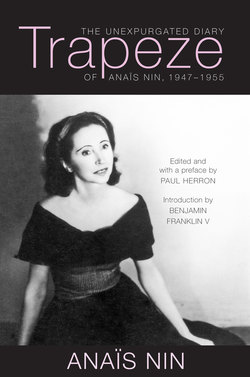

Rupert Pole in “Cleo,” his Model A Ford, 1947

| July 2, 1947 | New York. Beach with Carter and wife |

| July 3, 1947 | Staff |

| July 5, 1947 | Staff |

| July 6, 1947 | Chinchilito |

| July 7, 1947 | Jacobson |

| July 8, 1947 | Staff |

| July 10, 1947 | Chinchilito |

| July 11, 1947 | Staff |

| July 12, 1947 | Jacobson |

| July 13, 1947 | Staff |

| July 18-27, 1947 | Los Angeles. Rupert Pole |

| July 28, 1947 | Leave Los Angeles |

| July 29, 1947 | Mexico City, alone |

| July 30-September 10, 1947 | Acapulco |

| September 11, 1947 | Left for San Francisco |

| September 13-18, 1947 | Trip to Utah with Rupert |

| October 26, 1947 | Lecture at Black Mountain College; met Jim Herlihy |

| October 28, 1947 | New York. Gotham Book Mart party for Children of the Albatross |

| November 1, 1947 | Albert Mangones |

| November 5-6, 1947 | Bennington lecture |

| November 12, 1947 | Lecture Chicago with Wallace Fowlie |

| November 25, 1947 | Gonzalo Moré |

| November 29, 1947 | Radio broadcast, New York City |

| December 3, 1947 | Lecture at Berkeley |

| December 6, 1947 | Los Angeles to Mexico |

| December 8, 1947 | Bought house in Acapulco |

| December 19, 1947 | Rupert arrives in Acapulco |