Читать книгу Trapeze - Anais Nin - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA TYPICAL AMERICAN WIFE

1949

SAN FRANCISCO, FEBRUARY 1949

I moved to San Francisco after one more return to New York and attempting to live with Hugo on his houseboat, which he took on Long Island Sound. Was he trying to relive my life? To find me? Or to lure me by offering me what he thought I wanted? At the time I felt completely estranged from him. He was trying for closeness and I could not feel it. My life with him seemed unreal, a role.

He came to San Francisco, before Rupert did. I persuaded him to let me have an apartment there. Our relationship was at its worst then. We could not communicate. Did he think this was the end of it? I did not say so. I merely admitted to needing to be by myself at periods. He let me choose the apartment. He was angry, but we did not break. He left. I fixed it up with furniture from Goodwill and with shelves and glass bricks.

But I had not thought at first of Rupert living in the apartment. I had found a tea house in the back of a big house, in the center of a garden. I could see it from the road, near Ruth Witt Diamond’s house. I thought it would be beautiful for when Rupert came to stay with me on weekends; he was living at International House and going to forestry school at Berkeley. I still thought of the apartment as for me and Hugo. I fixed up the tea house. It was an enormous task. An unkempt old man had lived there, never cleaned it. I had to fill twenty boxes with garbage; for days I carried old newspapers and detritus up the hill for the garbage man. I had a shower built in the cellar. It was poetic. A true Japanese tea house.

Rupert loved it. I painted it, fixed it up, but it was damp. The garden was cold and damp. San Francisco was damp. The sun did not reach it.

By contrast the apartment was spacious, sunny, and with a beautiful open view of the Bay. But I felt Rupert would believe that I could afford the tea house, while he would not believe I could afford the apartment. I began to wish I could tell him about the apartment. So I concocted the following story and here it is:

“Darling Chiquito: I’m writing you instead of waiting to talk with you because sometimes I get intimidated by the big eyes of your conscience, and lose sight of my explanations. When my Americanization process began I was stumped by the following illogical law: I can’t get Americanized unless I’m self-supporting, and I can’t take a job with my present papers because I am here as a visitor, that is, not allowed to work for a living. To fix this I would have to leave the country for an indefinite period of time while they studied my case and perhaps risk never entering again because I would have to apply for entry as one intending to work and be self-supporting! Such are the laws. I was gravely concerned about this, as when I asked you if I could accept Hugo’s support for a year you felt definitely I shouldn’t, and I felt so too, yet I could see no solution. Finally, talking with a lawyer while Hugo was here, we reached this compromise. If Hugo paid my rent for a year, and could show the contract, it would suffice as proof of support and I would need not show any other proof. That was fine, except that I didn’t want Hugo to see the tea house as he would deem me romantic, living in an unhealthy, inadequately warmed place. And I certainly did not want him to pay for our tea house. So I tried to postpone all until he had gone, but as he had to sign the lease, I couldn’t, and so I had to accept the apartment or be sent to Mexico and not be with you for an unknown time and with fear of a refusal of a re-entry permit. Once I am Americanized then I can begin to work, or earn without having to leave the United States and return. Then I was disturbed as to how you would feel. I considered renting the apartment to a friend. Then I thought of many things: my belongings from France arriving and having no room for them in the tea house, our not having room for your music and a place for me to take up dancing again. I thought of waiting and letting you decide. I wanted to surprise you and have it fixed up. Many other problems came up. There are people I can’t imagine visiting the tea house, people I would not like to see there, like my brother, or some professors I know. I could see the tea house invaded by the wrong people and no place for our little house of love. I thought of how many moods you and I have, how we love Cleo and yet find Perseus useful on long trips, how we like casas and casitas, how you love a good kitchen and that we don’t have one in the tea house. Then we have no garage for Perseus, and sometimes during the rainy season our tea house will be very damp for your chest. And I decided to let you decide, to think it over. I feel we can always have the tea house as a retreat for our togetherness, but that you need space sometimes. And so darling, that is the story. You decide.”

Rupert, who had been slightly taken aback by the smallness of the tea house, took one look at the new apartment and decided very simply and without romanticism that it was a far better place to live in and for him to come to on weekends. That was the end of the tea house.

We live quietly. Ruth comes to tell me I owe it to the community to go to gatherings, parties, etc., but I feel when going out that I enter a colder world in which I am not at home. I only want to be with Rupert. On weekends we drive to the beach, which is cold, to the mountains, which are foggy.

Then came the ordeal of the poison ivy. Rupert was gathering leaves and flowers for his botanical studies, right in the hills surrounding us. That evening we went to a movie. The virulent poison ivy broke out on his face and hands. It was as frightening as leprosy. In one night the beautiful face was the face of Frankenstein’s monster. He could not sleep. I had to cover him with balm, clean the suppurations. He was inflamed beyond recognition. He was humiliated, cowered. We saw the doctor. He did not want to be seen. His eyes would be closed by crusts in the morning and had to be carefully washed. It was a nightmare for him. He suffered physically and in his pride. Once while he was taking a bath I saw his desire and bathed with him, a proof of love, a proof that it was not only his beauty I loved.

Recovery. I could not believe his face would return to normal—the delicacy of the skin, the delicacy of the ears. It slowly emerged unspoilt—a miracle.

We went sailing with Jean Varda, but it was bitterly cold and I dressed like an Eskimo. And we were becalmed and stayed in one spot almost all the time.

Varda is living in a loft. He gave a party. We arrived early and Varda was showering under a contraption used in the army, a pail of water pulled by a string, pouring water over him. Rupert played his guitar and sang. I was filled with anxiety. I felt Rupert was like the Crown Jewels and that would be stolen from me, that he could not continue to be mine.

On his trip west, Hugo had met the young filmmaker Kenneth Anger. Hugo bought a bargain movie camera and began to film. Kenneth encouraged him to film and not to study with anyone, to become self-taught. In Mexico he began to film whatever he liked, without plan. With time, adding a little with each trip, he finally edited and finished Ai-Ye (mankind), his first real film.

He impulsively resigned from the bank. He was free. He was living on his capital. It was a period of freedom and recklessness, economically and emotionally.

He left the 13th Street studio and moved to 9th Street, a furnished apartment that had to be transformed.

SAN FRANCISCO, APRIL 15, 1949

Rupert left the International House, where he was staying, and began to live in the apartment, going to Berkeley from there.

At six-thirty the alarm clock buzzes and makes me jump. In the long, wide bed, I turn to the right where I can see through a slit in the venetian blinds the little garden stretching uphill, flowers, the reflection of a ceiling of fog, and to the left where I look at Rupert asleep. His face causes me a surprise each time. How could a face be assigned with such finesse, so close to the bones, the bones so delicate that it might represent the essence of a face rather than a face of flesh? His tousled black hair: boy and man. His features have a generous, bold proportion. They were designed for a rich, full nature, on a face so delicate that they portray instantly the duality of his nature: a generous, expansive, full nature blooming on a vulnerable, fragile structure, in danger of injury, the full flower of sensuality and imagination on an oscillating stem of adolescence. He turns towards me, still half asleep, and kisses me on the cheek. Only later will the kiss of hunger turn into the possessiveness of desire, not on the cold mornings of duty tearing us both out of the warmth, cutting the sleep and the embrace short, sending me first out of bed so that I can wash my face and comb my hair and button on my slacks and sweater. I start the coffee and light the oven for the rolls. I push the button that gives heat. I open the venetian blinds. The fog has lifted and the sun dapples the breakfast table, the San Francisco Chronicle sign, the other houses, other windows, children starting off for school, other garage doors opening, men going to work, women waiting for the bus.

While I set the table Rupert goes to the bathroom. On school days he does not sing. On early mornings he is like a newborn kitten and not yet awake or aware. His blue eyes are without recognition of human beings. He has been wrenched out of the depths of sleep and he is still swimming in it. On other days, Saturday and Sunday, when he can sleep, he comes out with clear, open eyes and embraces me, rocking me, whispering, or inserting his tongue in my ear like a direct message from his desire, and I know that this signal comes from his manhood, by the kiss that is not tender, not adolescent, but hungry and aggressive.

When he is dressed I have to remind him of all he forgets: “Do you have your keys? Change? Handkerchief?”

“Will you make me a sandwich?”

If he is late, or if the gas has leaked out of old and tired Cleo who waits outside in the rain while Perseus stands sheltered in the garage, I drive him down the hill to the bus, like a typical American wife. We never talk very much. When I return I finish my coffee. I wash the dishes. Out of the window of the kitchen I look down upon a wing of San Francisco, white houses on hillsides, upon a span of the Bridge, on a stretch of the Bay, and beyond, where there is fog, Berkeley where Rupert is going to study forestry. In his room I have to empty the scrap basket of the dried flowers he did not paste in his botany scrapbook, pick up his clothes and hang them.

At eleven o’clock or eleven-thirty the mailman comes. It is a lone letter from Hugo, a very long one, describing his trip to Brazil. Our relationship is, for me, a playing for time, an edifice of lies, a postponement. I won the last game. He returned to New York on April 1st and I expected to have to go to see him but managed by infinite intricacies to postpone homecoming until June because he is going to France in May. In June Rupert will have a summer job where I can’t be with him. I can’t desert Hugo altogether and I can’t leave Rupert.

I await news from Dutton. I sent them The Four-Chambered Heart a few days ago, the story of Gonzalo without its sordid, degrading end, for Gonzalo, like June, had the power to descend to the greatest vulgarities, and I cannot even transcribe the slime into which our love dissolved.

I telephoned the antique dealer: will you come and see some antiques I have for sale? A Spanish-Moorish bedstead, an Indian lamp, an Arabian mirror, an Arabian coffee set, a Kali goddess. They have served their purpose. They furnished and decorated my days with Henry, my days with Gonzalo on the houseboat, and they were catalogued in my diary, glorified in the Under a Glass Bell stories. After that they died the death of objects no longer illumined by a living essence. My attachment to them died, and objects lose their glow as soon as we do not inhabit them, caress them. When they arrived from France after years in storage, I saw they were dead. Antiques. Wreckage from great emotional journeys. I had moved away. They looked incongruous in this apartment, this place. With Rupert I looked at the bed of my past loves, the lamps of my nights of caresses, and my memory swathed them in the robes of mortuary winters. They were objects I no longer loved, as I no longer loved the people I had shared them with, and I was eager to destroy them.

Letter from Anaïs Nin to Hugh Guiler:

San Francisco, April 1949

Darling: Our uncertain plans suspended our correspondence and I was happy to have talked with you by telephone—it is so much more real. I hope you are taking care of yourself, resting. I am always worried about you straining.

Your long letter about your adventures in Brazil was fascinating, really like a novel. And you write it all so vividly, so I felt I had been there with you. The funny thing is that what you felt about the man whose will forced you to take the trip under dangerous conditions is what I feel about you. I might say that if I tried to sum up the main characters of the life I lead alone it might be described as “effortless”—seeking to live according to my nature and energy. Of course I realize it is only possible due to the results of your work, but I hope you will strain less later. I do miss you and want to be with you, but in postponing the big move till June, I have an unconscious resistance to “strain.” I always hope that if I wait for you to be farther along in your analysis I won’t return to an experience that characterizes strain. On the one side is the love, the desire to be with you, but on the other is the sense of compulsion, the strain in your life that destroys me. We are now at this moment looking at each other but not at the same goal, or perhaps the same goal but in space. The result of my finding my true self is that I discovered a Cuban who does not like to force nature. Dios gana [God wins]. I admire your courage on your Brazil adventure, but as a woman I would dislike returning from this trip you wanted me to take with you depleted and exhausted. That is why here, though it isn’t the best climate in the world, I become absolutely healthy—by a petite vie, douce et humaine—where I never force myself. I work, but I stop when I have to.

In June I am hoping you will have finished your tense, quick trips and be ready for seven weeks of enjoyment. I do look forward to that. I also know I should be helping you now to entertain, so that gets me in a conflict of guilt. The resolution there seems to be one that I can’t take because of our love: to live on a small income but to live without effort, or forcing, that is the only “other” life I achieve alone. Anyway, I believe you are on your way to achieving a marvelous life and you are now all that I wished you were before: flowing and vital. Once the strain is taken out I believe we will want the same things.

Perhaps I am wrong to hope that the farther you push into analysis the happier you will be. I believe now that the short stays in New York were not good—too intense—and you felt resentful of my leaving so soon. When I come in June it will be different. Your feeling that I am returning for good may make a difference.

Anyway, I told you now about the course in composition I took all this year. It was interesting and strange.

I haven’t heard from Dutton yet. I speak before the Writers Conference April 8th at Berkeley.

You gave me money (cash and credit at bank) for five weeks. If you want me to come now, can I draw the cost of the trip from the bank and if I don’t leave on the 8th or 10th shall I take the allowance from the bank account? I await your plans.

People come to see the “antiques” but don’t buy.

Anaïs

SAN FRANCISCO, MAY 1, 1949

No alarm clock, a week of holiday. But Rupert is recuperating from an acute bronchitis. He needs his sleep. I always awaken earlier. A shaft of light awakens me, or the neighbor’s loud talk on the floor above.

The front room is flooded with sun. This morning it highlighted the newly stained table, in a pale violet blue, the last of our work on the furniture. Rupert has put a great deal of his own substance into the house. He worked on sandpapering the shelves and stained them. He is a perfectionist in craft. He built the coffee table.

But there is an organic weakness in him: the devastating bronchitis, the cough that racks his body. Lying in bed, defenseless, tender, he called me as I passed: “Come here.” His mouth trembled. “I am lucky to have you.” I took care of him with utter devotion. The love I feel is deep. His gestures move me. The fixity of his eyes, rigid with anxiety. The shape of his hands and feet.

Today I made breakfast and had coffee alone. I answered Gore’s letter, Hugo’s letter. On June 1st Rupert takes his summer job and I go to New York. I owe Hugo that.

Then Rupert awakened and began tinting the furniture. He is sad because the job is almost over and then he will have to face his dull, dry, monotonous schoolwork. So he dreams of Bali. But he does not dare to live on what I have because of his conscience and because he wants to be useful.

I wash dishes. I clean the apartment. I wash his socks (the first time I washed his socks was in New Orleans—he had work to do on the car, and I offered to wash his socks because he was suffering from poison oak and needed fresh ones). I go marketing. I buy what he likes. I have become fearfully domestic because the peace, the monotony of housework is broken by our wild lovemaking, our lyrical, stormy, lightning caresses.

Every day I question the mystery of my physical life with Hugo. What happened? What destroyed it? Was it inexperience on his part, and on mine? Was it inadequacy on his part? He has always reached the climax too soon. Was it dissatisfaction, sensual unfulfillment that estranged me from him? Now that I have this fulfillment with Rupert I have become faithful, domestic. I can sew, mend, repair, clean, wash, because there will be a climax, a lyrical moment, a sensation, a certitude of high living. The high living moment must have been absent from my marriage because I always had the feeling I was trapped by such experience, waiting, living en marge with Hugo, that this high moment lay outside, in the night, in the absent lover. Poor Hugo. What could I do? Sometimes I tried, delicately, to impart what I had learned, but his manhood rebelled then. Our lovemaking was tragic, ineffectual. He inhibited me.

A night of fog. Music on the radio. Leave the past alone.

I look at the dressing table I made from four shelves, a mirror, and six glass bricks. Brilliant, multicolored Japanese dolls on the shelves, princesses of a lavish glitter of gestures and clothes, like a Christmas tree of light, tinsel, satin, jewels. Elaborate, iridescent. I bought two of them. Hugo bought me the others, to delight me. When I went to New York in February I took one along for Hugo. I placed it on our dressing table. When we had to entertain wealthy and aristocratic Italians I placed the doll on the mantelpiece. Hugo interpreted it as an assertion of the childlike spirit. His analyst said, “Let her have all the props she needs.” The doll meant something else. It was the poem. It said, “This afternoon people are gathered together because of material interests, because they need each other to add to their power in the world, but they do not like or enjoy each other.” It is a ceremony without iridescence or beauty that I rebel against. I will be hurt in the process. And I was. The Italian woman was cold and arrogant and I lost my confidence. The doll on the mantelpiece pleaded for mercy. The afternoon among the mature, the assured, the cool ones was for me an ordeal. It had the character of torment, judgment, an inspection, a duel, and I felt incapacitated. I felt vulnerable and unequal. I explained this to Hugo. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to help him, it wasn’t that I shirked my responsibilities, it wasn’t that I didn’t want to please him, but that I couldn’t, I was unequal to it. I lost my confidence in the world. It wasn’t my world. I felt wounded by the arrogance of the woman, unable to hold my place, to assert myself. Hugo thought he had married a woman. I can be chic. I can look aristocratic. I have beautiful manners. But I am unhappy and strained.

I left the one doll on the mantelpiece and returned to the others. In my life with Rupert, they are not out of place. Rupert and I seek our pleasures, more humble ones; we avoid ordeals, we live by our wishes, we go alone to ski, we go to the movies, we seek those we like. But it is Hugo who bought me the dolls.

Around, around, around a circle of madness. Dependence. Rebellion. Rejection. Guilt. A childlike dependency.

I cannot grow in that direction. I cannot grow in arrogance, in a hard finish, in a gold-plated irony, impertinence or cynicism. With Dr. Staff I obsessively fought to be just to Hugo, to eliminate the neurotic obstacles to our marriage, to save Rupert from the tragedy of an impossible marriage.

“It is a most difficult decision to make,” Staff acknowledged. I sat in the same room where I first came to weep over Bill’s lack of feeling.

Back to Staff again, because once in Hollywood after Rupert left me, I sat on my bed weeping, and kneading and pummeling the pillows, repeating: “This is an illusion, this is an illusion.” But when he came to live with me it ceased to be an illusion, it ceased to be a necklace of intense moments, and we fell into deeper and deeper layers. Daily living.

Our rhythm.

Hugo could endure monotony, discipline, daily repetitions, meals at the same hour. Every unpredictable change, every variation, disturbed him. After I cook and wash dishes with regularity for a week, if I hint lightly to Rupert: “I am tired of dishes. Let’s go out to dinner,” he is not only eager for a change, but more often it is he who will suddenly drop his work and say to me: “We’re off.” I have barely time to don my coat, the car is already pulsating, there is a mood of freedom, a breaking of bonds, of halters and harnesses, a sudden influx of speed and lightness. Rupert and I leap out. No obstacles.

Poor Hugo. I am hoping that he is now learning to live more happily without me.

The dolls dance, contorted by extreme stylization. In the mirror I see the bed that sheltered me in Louveciennes with Hugo, with Henry, with Gonzalo. One of the woolen sheets I used in the cold houseboat was stained with red wine, Gonzalo’s red wine. But that has ceased to hurt me.

The present.

Rupert sighs over his endless calculations in his own room. He comes to mine to hear Brahms’ double concerto. Or I help him disentangle his rebellions. If he wants to go to a movie he does not enter boldly to tell me, but stands at the door, ashamed, guilty, suggesting a movie as if it were a crime.

He responds deeply to tragic, human movies, the Italians’ naturalness. He responds like an ordinary American boy to the charms of Rita Hayworth. He loves Westerns. In music he has infallible taste, but not in women.

SAN FRANCISCO, MAY 15, 1949

Que ma tête est lourde et fatiguée. No rest for me anywhere from awareness, insight, fantasy writing, analogies, associations. Writing becomes imperative for this surcharged head. I was happy when Hugo was in Brazil and there was no conflict. The day he returned and telephoned me from New York, tension again. Games and lies to gain time, to gain another month with Rupert. Two weeks left now, left to us. Rupert must take a job (dictated by his conscience), earn money and learn to fight forest fires during three summer months.

Hugo expects me in New York. He has planted flower boxes on the terrace of the apartment for my arrival.

Last days in San Francisco. Intense joys at night, in Rupert’s strong arms, an electric orgasm, a caress that kneads the flesh, sharp, keen pleasures given by his active, fresh-skinned, fragrant sex. The smell of an adolescent. Nothing aged, faisandé, sour, and all of it light, readily evaporated, like a perfume. The mercurial silk of the body, it slips between your fingers for its aliveness. I never tire of feeling his neck, his shoulders, his physical perfections, the shape of his back, his stylized backside, so neat, so amazingly compact, so amazingly chiseled for vigor and speed. Such finesse in his profile, the shape and carriage of his head. All form and lines. Nothing has been carelessly designed. There is no imperfection. During his severe bronchitis he allowed himself to speak like a child at times, requesting, yearning, complaining. But once well again he recovered his role of authority.

He was born in the fantasy house of Lloyd Wright. He was raised with unorthodox people. He does not like conventionality. But above all, he speaks of the closeness we have and makes plans for a lifetime together.

Drugs. When it is intolerable, I reach for my French books again, saturate myself with the delectable Giraudoux, with the poetic analysis of Jouve. I rediscover a world so infinitely superior to America that I lose hope for it, for its crude literature, its crude life, its barbarism.

We are back from botanizing, just up the hill across the street. Rupert carries the shovel; I carry a basket for the flowers and a trowel. He sits analyzing and classifying the flowers. I have prepared Spanish rice. The back yard is wistful with the persistence of the drizzle. The flowers hang their heads. Some of them adopt the raindrops like dazzling bastard children, and up the hill with Rupert I found one that made me exclaim: “Chiquito, come and look at the unusual flower; do you want it?” The flower melted in my fingers. It was a raindrop, pretending, expanding in a bridal costume reflected from the clouds, spreading false illusory tentacles of white lace on the heart of the leaves.

The ballet of Japanese dolls dancing on the shelves looks down at me lying on the bed. At times I think of death. I can believe in the disintegration of my body, but cannot imagine how all I have learned, experienced, accumulated, can be wasted; surely it cannot disappear. Like a river it must flow elsewhere. For example, for days I received the entire flood of Proust’s life and feelings, which has truly penetrated me, three times now, but each time more deeply—this is immortality, this is continuity.

The mockingbirds, the birds of California sing lightly, intermittently. At six o’clock the Spanish rice will be ready. Rupert will have finished placing his flowers in his scrapbook.

Once he confessed at night, two years after we met: “At first I thought you were impetuous and fickle, and that as soon as you had my love you’d go off. I was afraid of you.”

Another time he said, “I was never altogether satisfied sexually until I met you. With the others it required an effort to adjust rhythms. With Janie it did not go at all. This is the first time that it is perfect.”

Another time: “It’s so good when it is with the whole self.”

These statements give me confidence, but I lose it again when at the movies he raves over the cheap and obvious heroines, or when he meets Varda’s girl of eighteen, and when I said, “Would you exchange me for Varda’s girl?” he answered: “Only for one night and then I would forget her.” I have allowed my hair to grow long, as he likes it, soft and barely curled, très jeune fille. He likes gay and sensual blouses. He likes to see my shoulders. He likes that I love nature while not being just a healthy, dull, stupid or insensitive girl.

He is proud of my writing, even if at times it causes him embarrassment with the uncultured foresters.

In his small bedroom next to mine, I hear him sigh. He is bored and tired of forestry studies. He wears glasses. I remember the first time I saw him outside of his lover’s role. In love he was illuminated, resplendent. I saw him at the printing room where he was printing Christmas cards and was so surprised to find him serious, concentrated, shy and without luminosity. Sensuality illuminates him. But when he isn’t all aglow with either desire or gayety, then he is anxious, strained, haggard (so much alike we are in this). At the foresters’ dance, it was he who was out of breath from the folk dances, not I.

His only flaw: his temper. His tensions often become bad humor, and then he becomes critical, harsh. I can only use words applied to women for what he becomes: nagging, persnickety, finicky, and fussy.

Then he is the complaining wife and I the one rebelling against “details.” He wants me to save 13¢ on gasoline. He didn’t want me to have my hair washed at the hairdresser’s, I should do it at home. There is only one good brand of mustard and I am expected to look around for it in various shops. There is only one good brand of coffee. He becomes hard to please. All his frustrations with forestry make him exigent, whimpering, and I wear myself out. At such times the redeeming trait is that he is fully aware that he becomes impossible (as a woman during her menstruation) and is ready to acknowledge it. When he goes too far I get depressed or rebellious, but he soon wins forgiveness.

He is ready to do anything, to make any sacrifice for the relationship. He takes pains to efface the wounds. When we went skiing in Yosemite I became neurotic and discouraged because I could not keep it up. After I said, “You’d better find yourself a wife who can ski,” he replied, “Well, but then I’d have to teach her to make love as you do.”

The Rupert ordinaire, Rupert the American boy is there, but then he suddenly transcends it; he is more than that, he is an imaginative Welshman. He is touched with genius at times, at moments with intuition, with poetry never reached by his companions. He is more sensitive and complex. He is unique, and everyone recognizes his personality. Among the foresters he is known for his folk singing and his guitar. At their parties he entertains them with grace and without egocentricity. He invites them to sing with him or he willingly accompanies a song he does not know, a singer who can’t sing. Gently and without vanity. He moves me. When he is bad, it is eruptive, nervous, something merely to re-establish his exaggerated goodness the rest of the time, his control. Again I play the role of interpreter.

We have similar impatience. He scolds me for mine. But he loves that during the trip he never had to wait for me. I dress, make my face up, fix my nails and eyelashes, and my hair, all in the time it takes him to shave. And I can pack in five minutes.

Once in Paris I had a record of Erik Satie that I loved. I remembered it in New York and tried to find it. I couldn’t remember the title. It was the ever-recurring song of remoteness, the one that appears in Debussy, in Chansons d’Auvergne, in Carillo’s Cristobal Colon. It was a theme I wanted to hear again. It was the beginning of my new book I could not find.

Today sitting by the radio after breakfast I heard it and identified it. The other day driving to Berkeley I heard Debussy’s Sonate Pour Violon et Piano, and again I wept and experienced the fullest, wildest sorrow.

I am invited out by Varda, by Ruth Witt Diamant, but it means leaving Rupert alone in his room. So I either refuse, or if I do appear it is only for a moment, and only for enough time to realize I am lonely in the world. I am not close to anyone. I am closest to Rupert. I am happy at home. I am happier alone with Rupert. At ease. Satisfied. The world is complete. Wherever my love is, the world is complete. Our true connection took place in Denver, on the sand dunes. I don’t know why, but that lovemaking contained all we were, are, and would be to each other. It was a ring-like circle, it was soldering. There is lovemaking that has that definitive binding element. I felt it as such. Beyond lovemaking it was a marriage, because it gave us both a sense of gravity. Suddenly a man and woman discover the axis of the world. It revolves on this conjunction of male and female, the rotations of love become the rotations of earth, sun and moon, and gravity is achieved.

There is a sense of effortlessness in my life with Rupert because my feelings are with him; while he is working my love flows to his sturdy hands, to his warm-blooded skin, copper-toned when he is sunburned. Even when he is ill, his ears are roseate, his face has a warm color. Once during bronchitis, after I had made him perspire abundantly, I rubbed his body with Vicks, and his sex rose in excitement. He said, “I always feared this would happen in Harvard Hospital, or in the Army hospital, when I was washed or massaged, but it never did.”

But it happened with my hands on his body. Excitement.

RETURN TO NEW YORK, JUNE 1949

Letter from Anaïs Nin to Rupert Pole:

New York, June 8, 1949

Darling Chiquito: The first nights here were like 100,000,000 years long. I felt better when I got your letter. That is all I need, to know you’re well and still love me. I’ve thrown myself into my work day and evening. Not only reading manuscripts but writing on any subject, theme or item to prove versatility, and secretly investigating assignments with eyes and ears alert. I have hopes of seeing you one weekend in July, between the 20th and 30th if my publisher will let me attend the writers’ and printers’ conference near LA. I’m working for this, as it makes the three months seem lighter.

Dutton (and this is a compliment for you as well, my collaborator) thinks The Four-Chambered Heart is the best book I’ve done (it has more of a story to follow). Thursday they have the final conference. Following your advice, I also showed them the diary that they had earlier refused without reading it, but now they are laughing over it and getting interested. Oh darling, I’m trying everything, seeing everyone I should. Just a career woman now to fulfill our dream, and this is the dream I have when I can’t sleep. In February, on our birthdays, we will go around the world before you settle down to forestry—one long, good, fulfilling voyage—and I am working for this.

Sending you money to deposit into my account, from sale of books. Or if you need it for Cleo.

Te quiero profundamente. Please do not burn or scratch for my sake, so I will have something to caress!

Tu Limoncita

| June, 1949 | Dutton rejected The Four-Chambered Heart |

| July 16, 1949 | Return to Los Angeles |

| August 4, 1949 | Acapulco |

| August 11, 1949 | San Francisco |

| September 1949 | New York |

SAN FRANCISCO, OCTOBER 20, 1949

Father died this morning. The hurt, the shock, the loss, as if I had died with him. I feel myself colliding with death, breaking, falling. I wept not to have seen him, not to have forgiven him, not to have held him in my arms. He died alone and poor in a Cuban hospital. He collapsed Thursday. That is all I know. I received the telegram from Joaquín in the morning. I didn’t want to weep. It seemed as if I would die with him. Then I wept. I felt the loss in my body. This terrible, unfulfilled love. Never to have come close to him, never to have truly fused with him. I envisioned him asleep. I wept. I had to meet Rupert, my slender one, my lover of women, but near and warm. I wept on his thin shoulder. He was tender and human. So tender. We came home. It is strange. Life continues. You eat. You clean the house, but the death is there, inside you. The loss. The absence, the truth you cannot believe, you feel it but you don’t believe it, the pain attacking, dissolving the body. Guilt. I should have overlooked his immense selfishness as Rupert overlooked the great selfishness of his father. I should have sacrificed my life for him. Oh, the guilt. At other moments a destructive sorrow, the wish to die. The worst of me died with him, a craving for sainthood, the presence of madness, his madness. I fought not to be as he was, disconnected from human beings. I fought those who were like him, Henry, Bill, all the remote ones. I fought to be near, to fuse. From this death I will never heal. Rupert took me out to a movie. When I came home he sat in his room to work and I sat on my bed and sobbed. I can’t accept his death. It hurts. I wrote to Hugo. I don’t feel for Hugo anymore. It’s the death in me, the unbearable thought that to have integrity, to survive the destructiveness of others, we strike out, harm them, we are revengeful. I wish I had been a saint. Joaquín was sweeter, yet he writes me: “I tried to get close and failed.”

To work, to work. I feel the pain like a blow bowing my shoulders. Back in the pit.

Now I see the crime of loving young Rupert when I am closer to death and detaching myself from all he wants, all he seeks. Life with Rupert in San Francisco is coming to an end in January when he gets his forestry degree. It seems I have barely finished fixing up the apartment and we must leave it. Again to carry a trunk full of diaries to Ruth Witt Diamant’s cellar as I carried two valises full of originals to a vault. Again throwing away letters, papers, manuscripts. Again meditating, ruminating a new book, gestating, again flying to New York in two weeks, unable to bear separation from Rupert.

I see this looking inward now as a great act of courage, for I have lived two years with Rupert on the outside. In the sun, in the car, active, a peaceful life outside, no great depths, except of feeling. The nights are deep with vehement fusions.

NEW YORK, NOVEMBER 1949

After months with Hugo this summer, I spent a month at home with Rupert and then had to leave for New York, called by a letter from Gore and from William Kennedy of Duell Sloan and Pearce, who will publish The Four-Chambered Heart.

Hugo at the airport. His kiss is different. It is not sexual. It is affectionate. He tells me he has lived like a monk. “But why?” I said. He wants me to feel guilty, wants me to feel badly. He has deep resentments. His patience, his gift of freedom is a pretense; his goodness is a pretense to hold my love. Hugo is an angry man. He was angry before he knew me. I have done much to make him angry. I know this. But Inge Bogner, his analyst, traces the anger to deeper roots. Even when she goes away on vacation he gets angry at her. His mother betrayed him by sending him away to Scotland when he was five, to the severe, fanatically religious Aunt Annie. He is struggling to exorcise this anger. He pretended goodness to win love as I pretended goodness. He feared desertion. But there it is. He greets me differently. No one is to blame. Something about him has withered. Full of gratitude, indebted for all I have, even for my happiness with Rupert, I arrive spontaneous and am met with a willful anger that is deep-seated and not caused by me, at least not originally. The original sin of the mother—for that I have been the scapegoat. So the kiss is kind, paternal, there is no fusion, no deep elemental tension. He is authoritarian with the porter. He commands the taxi. A part of me withers. The taxi drive is spent in a veiled reproach for my absence, and although Rupert too suffers from my absence, there is a difference. What shall I say? When your analysis is over I will no longer need a refuge. I haven’t the strength for life in New York (true). He has had some birthmarks removed to be handsomer, to please me. I am touched, moved. When we get to his apartment on 35 West 9th Street, which I don’t like, would not have chosen (the only beauty of it is a terrace all around with a view, air, space), he has a bottle of champagne, but when we are in the bedroom together, I have a moment of such anguish that I fear hysteria or madness. It seems to me that if I let myself be uncontrolled, I will instantly destroy my life with Hugo. This fear and the control I must exert constrict my throat, and for two weeks I had a cold that hampered my breathing. Anguish when he is asleep, and I am aware of the distance between me and Rupert, and there is the feeling that I have forced myself to come here, but this is mixed with a pity, an awareness of his struggles, his loneliness, his needs, his generosities, his good will. So I rush to Staff!

My relationship with Hugo is deep. With Rupert it is easier because it is not as deep. Staff has struggled to efface the image of Hugo the father, and as Hugo has been shedding the role, it has been successful. I see Hugo younger, less severe, more inadequate, more bewildered by life. I return home aware of Hugo’s difficulties: he feared insanity (his mother is insane); he feared desertion.

Every morning for two weeks I went to Staff. Every night I had the sense of hysteria and of confinement. I could not bear to fix up the new apartment for our future life. I stalled. I took sleeping pills. With this I had to face intense activity with Kennedy, other people, telephone calls. An important friendship with Kennedy. Yes, love for Hugo, but no desire, no desire to live with him. Yet there is a fear of Rupert too, of an inevitable catastrophe. Only with Staff could I explode. Yet I cannot free myself of Hugo. He is part of my relationship with Rupert. Through Rupert I sometimes reach a Hugo who might have been. I reach the Hugo I first married and the first five years of our marriage. And I can understand Rupert as I did not understand Hugo. Rupert has the same seeking of responsibilities, the same conviction that to assume responsibilities is the role of man. Then the two figures begin to melt into one another. I wish I could feel towards Hugo as I feel towards Rupert. And when I envisage my break with Hugo I feel as if Rupert and I are two orphans, and I feel lonely.

But after two weeks with Hugo in New York I must leave.

The alarm clock. Hugo has to go to Dr. Bogner. He has done this more intensely, more thoroughly, than I did. It is his nature to be tenacious, obsessive. That he is fighting his resentment works in my favor. Because as he received me with indirect reproaches, or when I postpone furnishing the apartment, he believes it is his possessiveness that drives me away.

Millicent the maid is there, aging, withering, working now for the sake of her grandchildren.

My father died mad. He did not understand what happened to him. I want my suffering to be useful. I want the novel to teach life. I want the novel to accomplish what the analyst does. Without Staff I would have gone mad too.

I only wish I could have helped my father to die at peace with himself and others.

SAN FRANCISCO, NOVEMBER 1949

I arrive at the airport at about six-thirty in the evening. It is dark, and, as usual, sharply cool, no softness in the air, the wind waiting to swirl, fog waiting to mantle the hills. Rupert hides behind a column, to surprise me, then leaps forward towards me and kisses my lips aggressively, hungrily, emphatically. The first time I had been away after we had begun to live together he said, “Never do this again. I suffered.”

He has said each time: “I was lonely.” I always think he will take advantage of his freedom, but he doesn’t. This time he said, “I tried to enjoy myself, but failed so miserably. Went to a dance at Berkeley. It was so dull. After that I stayed home and studied.” As soon as he has exams to take his face becomes pale, tense, anxious. His eyes are shadowed, his face drawn. In the car, with my valise in the back, and his dog Tavi between us, he kisses me hard.

Elation. Elation. Elation. He drives the big green Chrysler. I tell him about New York where I went ostensibly to help Duell Sloan and Pearce with publicity for The Four-Chambered Heart. When we reach home he lights a fire, starts to cook a steak. He opens a bottle of champagne. He shows me the big windows he cleaned. He bought me a present that will come later. I bring him a new book by his step-grandfather Frank Lloyd Wright, published by Duell Sloan and Pierce, a beret from the Spanish restaurant. News: how much Duell Sloan and Pearce is doing for me, friendship with editor William Kennedy, dinner with Charles Duell, people I met, my lecture at City College.

We went to bed early, to possess each other in the dark, his slender body like mercury between my fingers, his arms so strong, his strength pouring out like the strength of a cat, unexpected, vaster as it extends out of softness and fur, as it extends from Rupert’s finesse and sensitiveness.

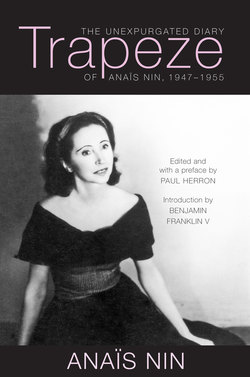

Rupert Pole playing guitar for Anaïs Nin

Sunday is a day of sun. He is working on a map he must design of the canyons behind Berkeley. So we make sandwiches and go out to walk through the hills. I wear my orange cotton dress from Mexico. It is warm. I am at peace. I am always at peace alone with Rupert unless thoughts of Hugo intrude. At peace, yet with a knowledge that devours me with anxiety, a knowledge of future tragedy. It is time, time I play with, time to allow Rupert to finish his studies, so he will be able to earn his living, time to live with him as long as possible. Staff said to lie to Hugo would be to gain time until Hugo’s analysis is over and he has the strength to face my departure. But Staff also says Rupert is an aspect of Hugo, that Rupert is a Hugo without neurosis, without sensual repression, a Hugo without his destructive mother or Scotch aunt who beat him, a Hugo young and free. He is present in the relationship with Rupert.

But Staff did not explicitly say, “Lie to Rupert.”

My feelings don’t lie. What is a lie? Is it a lie when I leave San Francisco to fulfill Hugo’s patient vigil?

Night, fulfillment, fusion. Yes, fusion.

NOVEMBER 10, 1949

Rupert graduates from forestry school

Letter from Hugh Guiler to Anaïs Nin:

New York, Sunday, December 4, 1949

There is no use coming back to New York until I work this thing out further with myself. I believe now the truth is, and there is no use concealing it from each other under a lot of words, that I have been angry at a whole accumulation of things in our relationship, and you have been too. We admire each other, we have pity for each other, but in our actual actions and attitude towards each other we have both shown that for the time being, at least, anger is stronger than the other emotions. As long as that lasts, we are going to make each other unhappy when we are together, and I for my part do not want to inflict this on you anymore until my anger disappears.

I appreciate the great effort you have made to solve the problem by capitulating (as you think it is) between the life you want and coming to New York. But every sign indicates that you cannot do this without a splitting conflict, even to wait until my analysis is finished, and will, on your part, in spite of every effort to the contrary, result in unconscious acts that show your own real angers.

And there is no need to fool ourselves that these angers on both sides are all out of the past. You began to deal with this honestly when you said there are certain sides of me you just don’t like and have no feeling for at all. That is today and not the past.

I now realize we have always been under cover of one excuse or another, arranging to be apart a good deal of the time, except during the war years when we could not. The truth is we were not together more than momentarily and spasmodically during the years after 1928 when I took over the trust work in Paris and started traveling, with your approval and encouragement, “to preserve the marriage,” you used to say. While I had the Trust Debt in Paris I traveled I suppose about six months out of each year. Then I went to London in January of 1938 and you took the decision not to accompany me, so I paid only weekend visits about once or twice a month over the next year and a half. We did not do this “to preserve the marriage,” but because we were too unhappy living with each other all the time. I probably fooled myself about this more than you did, as I am sure your diary shows. The periods of being together were therefore also charged with exaggerated feelings in an effort to make up for what each of us thought we had been depriving the other of in the intervening period, or what we thought we had the right to receive because we had been deprived of something.

The greatest problem I have, and one that has created a big problem for you also—accentuated by your need to have someone dependent on you spiritually, you in turn being dependent in other ways—is my over-dependence on you. In this respect I have been like a child and now after fifty-one years of childhood, or reversion to childhood, I must have some time and learn how to go out myself, make friends myself without you, and to acquire a whole new attitude that is not at every turn simply another road around you.

You have asked me a hundred times: “Why are you so dependent on me? Why do you have no world of your own? Why don’t you know what you want—colors in this apartment or anything else concerning our personal life? Why don’t you express yourself directly instead of always through me? Why do I always have to be your soul?” You were really saying that you were my soul and were really asking: “Have you no soul of your own?”

All that was in part true, and I have at last awakened to it and all it implies. It has been a terrible burden for you to carry even when you said you liked carrying it and so often said that you were my soul. In the last year or two you have been trying to tell me that you could no longer carry that burden, and now I understand I really agreed with you when I took up the analysis, which represented my effort to carry my own responsibilities.

But then when, as a result of analysis, a soul of my own did start to appear and you began to see the shape of it, you were taken aback. It was not what you had imagined, not what you had wished for, or at least only in part, and it was then that a more serious withdrawal took place on your part.

Dr. Bogner has only last week broken the news to me that I have been deceiving myself into thinking that I am an artist. She says I am obviously primarily a businessman and only secondarily, and on the side, an artist. It came as a great shock to me, but I believe she is right. Much of my artistic endeavor was due to my despising myself as a businessman and feeling that I had to prove in some other way that I had a soul. But the business world represented reality for me and, to the extent that my artistic activities were done in the spirit of a flight from reality, and the forms they took could not be other than exaggeratedly remote, introspective and inhuman. Then on the business side there were corresponding tensions and exaggerations because such activities were under constant attack from within (myself) and from without (you).

And I will probably continue to keep up this combination of unenslaved, flexible business activities and making movies, as well as my general interest in art, for the rest of my days because that is who I am.

I am not going to take this opinion as final because I have found from experience that so-called artistic judgments often conceal neurotic lies.

The artist sometimes has something valuable to contribute and at other times simply sits behind his own kind of defensive barriers, except that he has the nerve to claim that they have something sacred and privileged about them that must be given special consideration. Everyone, I believe, is out for power and achievement in different ways, and you today, for example, are just as ambitious about your books as I am about my business. What is unfair, I think, is that you have tended to act as if your ambitions were in some way exercised for nobler and loftier aims than mine in business. That I now reject completely, and I believe you are honest enough, when you really think about it, to do the same. Childhood neuroses often compel you to act differently from what you really believe.

But you are what you are and certainly I am not the one to criticize your ambition to have a successful career of power and achievement, for I have nothing against that. I realize this furthermore is a structure that has been built up from your earliest days and that is something very real to you, and assumes an importance in your life so great that you feel you have to defend it at all costs.

Your behavior arises from a dissociation in yourself from one kind of business in order to carry on another kind, that the kind of business you chose did not feed you and that you therefore had to take from the one you dissociated yourself from to support the other.

The question you must ask yourself is whether you want to continue to be married to the person I have presented to you as my real self, whether you can continue in such a marriage without the unhappiness that has resulted from each of us keeping before us a false and unreal picture of the other.

But you see, darling, I have had a great shock, really from waking up suddenly and realizing that during my sleep I have been subjected to a long series of shocks, and I must have some time to gather myself together and gain new strength in myself, so that I will no longer be angry, as I will be as long as my confidence has not returned, which will take time after such a violent upheaval. You still write in the sense of being compelled to pay up for something, and I do not feel that you will be all right with yourself or with me until this has changed into something more positive; until you really feel that the two businesses (whether the two between us, or the two in yourself) are ready to go hand in hand towards a common goal, rather than one hand must pay for having taken bank notes out of the other.

For I am now completely disposed to accept the facts as we have discovered in each other, and any forcing at this time will only make it impossible for us ever to work out a relationship on a new and realistic basis.

I think it may be best for you to consider San Francisco as your headquarters and your stays in New York as visits only. As I get back into the foreign field I will be spending more and more time in Brazil and Mexico on business. We can then see how much time the demands of our respective careers permit us to be together.

We never had the peace that comes from being sure that each of us was accepted for himself and herself. We have been always in a state in which that self was threatened.

So now, Anaïs, I know you for what you are and you know me for what I am. There is no need for either of us to make the slightest demands on the other. When I get a little more on my feet I will not feel threatened anymore, and I have no desire to take away from you your individuality as an artist or a woman, or do anything but give you the fullest reins to your career. Let us expect little of each other and perhaps we will get something. And I assure you there will be no more ultimatums on my part if there are none on yours.

Hugo

Card from Anaïs Nin to Hugh Guiler:

San Francisco, December 1949

Dear Monkey, I think of you. I admire your great courage to be reborn as a new man, a damned interesting man. Please take care of yourself. Do not think harshly of me for expressing, or rather trying to find my real self. It was just as disguised as yours. I had to dig hard for it.

Saw Man and Superman by Shaw; remembered your having enjoyed it. I guess I found my match in you.

Your cat.