Читать книгу Trapeze - Anais Nin - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLA JOIE

1948

JANUARY 1948

Acapulco

NEW YORK, SPRING 1948

Rupert’s gift to me was a special, selected view of America. The nature was beautiful, full of variety and surprises. Canyons, marshes, fields, rivers, swamps, desert lakes.

During that trip none of his dogmatic traits were revealed to me. True, he talked about a home, wife and nine children, but I did not believe him altogether. We played at my being the other woman, the foreign woman who would lure him away from his home now and then!

I talked about my travels, the panorama of Europe paralleling America, sometimes created out of contrast, sometimes by association. Two warnings my heart did not heed: one, that his life was not interesting, just ordinary; the other, that he did not know or understand his relationships with other women, his lover of four or five years, or his ex-wife. I probed in vain. He gave me a blurred, confused image, with many gaps and black-outs.

Once he was jealous of my abundant mail and threw it on the floor.

I had my difficulties on that trip. My eyes were wind-burnt and caused me much suffering and humiliation. In South Carolina I wanted to quit; I felt homely and inadequate. Rupert was kind. But I realize now that true kindness would have been to put the top up, and that he never did. I had to learn the hard way, to find glasses with sides against the wind, to wear a base of makeup over my eyelids and face as protection.

I also felt utterly tired; we kept a daredevil pace, and this intensity, without pause, made the trip an ordeal.

On that trip I accepted his leadership totally. I did not know the road, the restaurants, the motels, or anything about cars. He was an experienced traveler. So Rupert may have had the illusion that I was easily dominated! I enjoyed his leadership then.

We stopped to see Henry Miller in Big Sur. The road to his home was steep and dangerous, mountain driving, and Rupert’s car wasn’t quite equal to it. But as we climbed, the view of the sea below, the rocks, the pines, was beautiful. The car drove into a courtyard, and there was Henry sitting out of doors, typing. He seemed healthier than in New York. He was proud to own the modest cottage we entered. It was simple and uncluttered, reminiscent of the old Henry’s tidiness. His wife Lepska appeared. There was tension between them. He criticized her. He thought my trip west and to Mexico was a flight from my life in New York, and that he should help me in some way. I made it clear I needed no help.

I should not have visited Miller. As soon as one ceases to know a person intimately, the knowledge of them is from the outside, as if you stood at a window looking in. Intimacy takes trust and faith. That was over.

“See! See!” said Rupert, “See the Lord’s candle cactus flower.” When I saw them I thought: we are nearing his home. It is time for me to return the ring he gave me so that during the trip I would be known as Mrs. Pole. In so many registers all through the United States, Mr. and Mrs. Pole. But when I tried to return the ring Rupert turned his face away: “No, keep it. As a remembrance of the trip.” It was the wedding ring from his marriage to Janie. On the last day of our trip together, entering Los Angeles, he expressed sorrow at the termination of our dream.

“It’s hell,” he said upon awakening to the reality of our parting. But he did not act to hold me, to affix me. He surrendered me. I wept as I sat at the airport, watching him drive away.

There was a honeymoon couple being celebrated, rice was thrown, a champagne bottle was opened, and the cork fell at my feet. I was weeping and looking at the couple. They did not love each other as Rupert and I had loved each other during our eighteen-day trip, yet they were married, secure for years, and that would never happen to us. We were separating, perhaps forever.

“Deep feelings have continuity,” I said to Rupert before leaving, to sustain my faith, but in reality there was nothing to reassure me. He was entering a new profession: two years of university courses to attain a degree as forester, and a forestry job in the summer.

I asked, “What would you have done if I had run away, gone to Europe?”

“I would have dropped my work and pursued you, brought you back. In New York I wasn’t sure you’d come with me.”

“Suppose I hadn’t at the last moment?”

“I would have abducted you.”

As we parted, I was returning a comb, a newspaper, and I said, “Do I have anything else of yours?”

“My heart.”

I returned to New York, to all my nightmares, to find Gonzalo still preying upon me, taking, asking, destroying the last shreds of respect, of illusion. Life with Hugo, insincere, a role. Then came a government injunction that I must leave the United States until a re-entry permit was in order. I left for Acapulco alone. In sensual, drugging Acapulco I wanted Rupert desperately. He haunted me. I haunted him equally. He wrote me that he saw me peeping behind every tree. He wrote of wanting me. He wrote of needing to be with me, but he didn’t write: “I’m coming.”

But just before last Christmas he did come to Acapulco. I had a little home and rented a car. All that I had imagined when I had been there alone took place and was fulfilled. We swam. We made love wildly in the tropical nights, after siestas. We took a trip. He got ill. I nursed him. We lived in rhythm. No clashes. We spent two days in Taxco. The only anguish he caused me was by turning to look at every pretty woman, and once when a Mexican girl stared at him he turned completely to stare back at her as if I were not there.

I am aware of the reality of our relationship. Rupert is kind, responsible and loyal, but he is susceptible to women’s charms. He has an adolescent curiosity and multiple enthusiasms. I am not to expect faithfulness.

Three days at Ensenada. When we got into the car, as for our first voyage, Rupert became free. He changed, expanded, grew wild. He became Pan. We were sitting on the bed talking. He has a brusque, impetuous way of throwing himself on me. We had three days and nights of wild and frenzied passion. Sometimes it begins gently and ends in fire, or sometimes it begins with fire and ends in gentleness, but it is always complete, all the movements are there, slow and sad, quick and gay, a rhythm below the surface. The sea, the sand, the wind, the trees are marshaled for our desire, our décor, and our language. Our moods are their moods. High, low, cold, warm, peaceful, tempestuous. Very few words. It is alchemy. Is there a mysterious rhythm between people, mysterious flows? Is it that he turns off the music I don’t like at the precise moment it grates on me, or that I am silent when his nerves are tired from driving? Is it that I sit passively in the shadow of his driving, basking in his leadership, his swift decisions? “We sleep here. We stay here.” His lightning quickness, his easy entrances and exits, his restlessness at restaurant tables. Oh, darling, how our bodies fit into one another and how our two vehemences knead caresses into each other to the point of pain. The fever mounts. In sleep it coils between our hips. Our faces veiled and dissolved by sleep, eyes closed, his desire is there, taut against my hips. In sleep he turns towards me, in sleep, in sleep . . .

The road swallowed us. The night. The mountain. A heavy snow cloud lying over the mountain, over every crevice, falling like a hand over us; it aroused the feeling of a caress, a union, as that of certain trees paired together, the aspen and the pine.

Dawn, day, and night were welded. Food a delight, drink a delight, and words too simple to contain this well of music made by our collisions, our desires, our caresses. Bathed in music, in the quick drumming of his fingers on my body, drumming out of my body every cord, and in the core, the vortex, the volcanic center where the two points of fire meet, a possession takes place of such high alchemy that no element is missing and each one has fused, not one drop lost or strayed or foreign or contrary.

Return to New York.

LOS ANGELES, MAY 8, 1948

The book entitled La Joie by Georges Bernanos always entranced me not for its contents as much as for the power of the words: La Joie, the mystery, the quality of an Unknown Land.

It was the unattainable state. When Rupert, a year ago, asked me to leave New York with him, I did not know it was to be a voyage not only across the United States, pausing at New Orleans, the canyons, but that ultimately we were to reach this new land together, this unfamiliar country of La Joie.

We are in my Hollywood hotel room, anonymous and banal, but white. His pipe lies forgotten on my desk. His bathing suit hangs in my bathroom. He, the volatile, the uncapturable Chief Heat Lightning as I call him, has left, but he is not lost. He has to sleep at home because his stepfather Lloyd Wright is severe, because he has to be up at seven to be at the College of Forestry at eight, because his mother is conventional and worried about his reputation, but he will telephone me at midnight, or earlier, every night, of his own free will. And when he can, he will rush over. His clear, light, breathless voice of a boy. This habit only began a month ago when I left for a lecture in Houston, one of the intermittent trips he imposed on me by his fear of permanence. When I left, he said over the telephone: “You have all my love.”

It took years of sorrow to learn these airy birds’ spirals around the lover so that the love should never crystallize into prison bars. Flights. Swoops. Circles. For a year I circled around him so lightly, so lightly. And so it was away to Houston for two weeks, and a return to California with Hugo who then returned to New York to complete his psychoanalysis. Rupert, then anxious, said over the telephone: “I missed you. I need to be with you again.” And he came over one night in Cleo and drove up the hills and we lay under a pepper tree, so avid, so hungry. Then he began to call, as we can only see each other on weekends.

La Joie. The present. When he comes he wears the sandals he bought in Acapulco. He lost the peaked green Tyrolean hat he wore on his trip, which gave him such a pixie air, for his face is small, pointed, and is eclipsed by his eyes. His eyes. His entire being is concentrated in his eyes. So large. So deep. So remote and yet so brilliant. Tropical sea eyes, sometimes veiled as if he had wept, passionate. I leap at his arrival. The current is so strong, a current of fire and of water, of nerves, and of mists, of mysteries.

Two lean bodies embracing always with vehemence, except when he is tired, so very tired, and then he rests his head on my stomach. If we drank the potion the first time we made love in New York to the tune of Tristan and Isolde, neither one of us acknowledged it until a year later, acknowledged the impossibility of separation. For after two weeks in Acapulco, he was able to leave without any plans for the future. He feared my presence in Los Angeles because he had too little time and imagined a demanding relationship. But when he saw how I behaved, how I disappeared, did not even call or expect him, weighed so little on him, he learned to enjoy the short moments with me. It was not until recently that he uttered the words I needed to hear: “You are the closest; no one has ever been closer to me.” Or: “You understand me so well.” Or: “We always want the same thing. I approve of you as I didn’t of Janie. But Anaïs, you are not being given all that you deserve.”

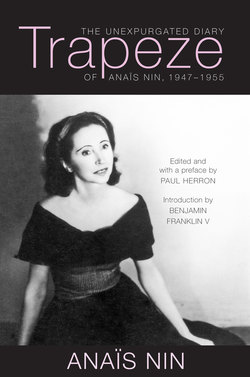

Anaïs Nin signing her books in Houston, 1948

“Lord and Lady Windchime,” I say in our moments of aristocracy, for he has that to a high degree. Lord and Lady Windchime go out in Hugo’s gift to me, a Chrysler Deluxe convertible that Rupert baptized Perseus. Perseus is exchanged for Cleo for long trips. Perseus has speed. Cleo has a dogged, spirited character. Perseus is polished and new. Cleo has gusto.

When we first met we were both poor, badly dressed, worn out, unhappy and defeated by life. Today he is no richer but he has a good home, refined, artistic, comfortable; he goes to UCLA every day. When he comes, we pack our bathing suits and drive to the beach along the richly flowered roads lined with dignified palm trees. We swim, we lie in the sun, we sleep. Or we run along the edge of the sea. Another time it is dark when he arrives. I wear my black and turquoise cotton dress from Acapulco. We rush to a movie, where we hold hands and where he laughs so exuberantly that he squeezes me to suffocation, and his gayety is expressed by his encircling me with his two wiry arms. And always this firm, strong, feverish lovemaking.

This love is full of sparks, and it is blinding. There is a potion that was drunk on our first trip, a mingling with the desert, the canyons, the mountains, a part that is mythical and dreamed. He who never planned, never crystallized, never foresaw, never promised, never longed, now says, “Next winter when I am in Berkeley you could take a little house in Monterey.”

I am awakened by the singing of birds. I cannot introduce them. I ask their names and then forget like a careless hostess. But they sing well and gaily. The sun shines through the venetian blinds. I have a choice of beautiful dresses to wear. (Hugo has resigned from the bank, has made money on the outside, and travels again as he used to and wanted to.) The pleasure I have indulged in for the first time in my whole life, of dressing according to my taste, of taking care of my body and face. I walk down the hill to breakfast at Musso. The banality and vulgarity of Hollywood does not disturb me. I see another Hollywood, young artists of all kinds. I help Rupert to increase his knowledge of art, to develop taste.

At night, alone, sometimes I suffer again from the mysterious malady of anxiety and marvel by what alchemy this is transmuted and given to others as a life source, wondering if it is not the alchemy itself that is killing me, as if I kept the poisons in my being, sadness, loneliness, and gave out only the gold. Everywhere I go life and creation burst open, yet I remain lonely, I remain without the twin I seek.

The oneness with Rupert is being destroyed by its intermittences, leaving me in between in deserts of mistrust.

This morning I got into my car that I learned to drive painstakingly and now enjoy. Alone, still amazed naïvely at the miracle of driving a beautiful, suave, powerful car in the sun. I go to Elizabeth Arden where the two women who attend to me have read my books, pamper me and come to my readings, and are proud of me. A quest for beauty, to efface some of the harm done by my years in the hell of New York. At times it seems like a convalescence. The sun shines on the nickel of the car, on my new dress, on my new dash, on my new confidence. This image of the quest for beauty is a fulfillment of a childhood dream, for when I was a girl I had to wait once for Tia Antolina at the Elizabeth Arden salon and I saw her appear so groomed, so radiant, so beautiful. I longed to be able to enter as she did and reappear, smooth as porcelain, a glitter of the eyes enhanced by eye-drops! Oh, Anaïs, such frivolity. No longer ashamed, for the deep life runs securely like a river, and the rest is adornment. And I no longer fear to be cursed by my father’s shallowness for daring to fulfill a natural elegance that is suitable to my body and face. I reappear then, as my beautiful Tia Antolina, powdered and ironed, patted out and refreshed, and get into my Nile-green car. When I return there is a letter from Hugo, finishing his analysis and planning for our future and “remarriage;” there is a letter from Bill Pinckard scolding me because my letters are impersonal (after two years it is he who is looking for a personal word as I used to look in his letters for a sign of love). He is on his way back from Korea. There is a letter filled with newspaper clippings on Under a Glass Bell, just published by Dutton. There are telephone messages from Rupert’s father, from Paul Mathieson, Kenneth Anger, Curtis Harrington, Claiborne Adams, other friends. There are flowers from an admirer. I can do as I please, but I can’t write. The present being beautiful, I can extract from the past its essence without pain. But still, I like this moment. I am absorbed by my love for Rupert. I meditate on his strong, hardy, rough eyebrows, his woman’s eyelashes so long and thick, his passionate eyes. His long deer neck, his lean and wiry body. His strange, unpredictable nature, chaotic, full of intuitions and seeking in nature a reality. I see him playing the viola in quartets at home, planting the lawn, helping his mother, cleaning the windows, taxiing the family, doing his homework, rushing to school. When we drive into the desert, Rupert knows the names of the trees and flowers; he is familiar with the roads. In Acapulco once he got very ill with a high fever. I was frightened. I remember the fragility of his face burning in my hands, a fragility like mine, though ultimately strong with will and spiritedness and a desperate courage. His lungs are not strong, but instinctively he seeks to harden himself, to lead a healthy life.

Chiquito, I call him.

How gaily he came Sunday, pretending to be drunk and sliding down the stairs, three steps at a time, dragging me by the hand, running to the car.

The birds here sing at night.

As in Acapulco, there is a constant air of Fiesta.

He loves what my sorrows have made me, my efforts, my courage, my aspirations. He loves what I have created, lost, loved, surrendered. With all his beauty, he looks upon the beautiful girls in his college (he could have them all) but he says, “They do not have this . . . this . . . this . . .” (he cannot find the words) “. . . this warmth you have, this growth.” C’est moi qu’il aime, my flavors, my elixirs, and I feel worthy because it was my labor, my effort, my struggle to become what I am, every word, color, every form I had to make, to create.

Last night: he was asleep on my breast, and I was caressing his infinitely delicate temples, the sleep veil over his face. It was three o’clock. He should have been home. We lay there in a trance of human sweetness. We had laughed at the movies. His talk and his words are but a small fraction of what he knows, and by this secret other sense we commune, we mingle.

Beethoven Quartet: on Saturday afternoons Rupert plays the viola in a string quartet. He asked me to go to his home yesterday to hear them. His face, leaning over his viola, was so beautiful and grave. So pure and emotional. The gravity of his wholeness. He plays with his whole being. This slender body contains passion and music. His bare arms are wiry and strong. His small, square hands so lusty and yet so sensitive. He is sad that his hands are not beautiful, but it is their character that saves him from too much delicacy, that gives a balance to his delicate face. His strong, square hands and feet save him from being too exquisite, too aesthetic. He plays with the same vehemence with which he makes love. Listening to him, I knew this was his language.

He wants me to study piano so I can accompany him.

Once again the diary becomes the extension of moments I want to retain forever. You cannot enclose fire or tenderness, but their echoes, their vibrations, their imprints. Love is the drug at first, and one is asleep during its fecundations.

“It’s strange, Anaïs, that I cannot take you for granted. Other people, you feel, will love you forever. With you I feel I must begin anew each time. Or is it that you mean so much to me that I fear losing you and I make greater efforts?” Jealousy is our only enemy. His and mine. In Acapulco, when the son of the man who rented me the house came to the door to deliver a message (an invitation for New Year’s Eve) or stopped his motorboat to hail us while we fished, to invite us to his father’s house, Rupert was anxious.

There are times when he makes love to me so profoundly, so magnetically, that I want to cry out, and the moan that seeps through is a faint echo of the wild turmoil of the body in this lightning storm, this charged current, vibrations with such violence through the nerves, the moment when he enfolds me, encircles me. Once he locked me in his arms so vigorously, so hard it left me breathless, and he murmured: “I’m just an inhibited man, but all I can say I say with my arms around you.”

After the quartet it happened we were both high-keyed, elated. I said, “Let’s run away” (from his home, mother and stepfather). We climbed into Perseus and drove to the sea and to an amusement park. And then I found my fear again, all the fears I thought I had conquered, fear and terror of speed, heights, the scenic railway, of violence and darkness, of labyrinths, of enclosures, of chutes, of darkness, traps. Why? Why? Rupert holding my hand, Rupert unafraid, Rupert elated by danger.

I am not made for happiness. Will I hear the birds sing again? Will I feel pleasure tomorrow when I see the jacaranda tree in bloom? Am I condemned to tragedy? Rupert and I had talked of jealousy. That was it.

And I had a dream. Rupert was telling me about a woman he had seen at a restaurant, and was fascinated with. He had made a drawing. He was asking me how to conquer her. I said, “Must you torment me by discussing her?” I sought him, and went to the restaurant. I examined the drawing of the woman. She wore an oriental veil, a Spanish mantilla that half covered her face. It was me.

Last night, returning to my room, he wanted to stay all night, so we had passion and fell asleep locked together until dawn. He is my music, my dance, my wine, my sea, my mountain, my fever.

And he has an important role to play, for it was he who took me by the hand and led me into nature, who took me out of artifice and into my own innocence again.

His airiness—how I love his airiness. Today he had only a moment with me. He leaped upon me and enveloped me so that I found myself caught between his legs, between his arms, and lying down.

With equal agility he climbs into Cleo and vanishes, and I feel a slight constriction of anxiety. Then, ironically, it is I who enter the hairdresser’s to have my hair washed and the girl says to me: “You always look as if you were about to fly away.” The first day she had said, “Are you a ballerina?”

Rupert in his car and I in mine. At San Diego he was given a car to deliver to his mother. And as he drove it back I had to follow in Perseus. It took all my wits, dexterity, and nimbleness to keep his pace! And how I laughed when even while driving in another car he kept pointing to things I must see, as he did all during our first trip. Thus I choose always the one who will take me out into the open, and my interior journeys become the journey outside. Rupert is always outside, always watchful, alert, responsive. Only after playing his viola does he sink into a mood, distance, absorption. The music sucks him under, into silent depths. He said once he had sent me away because he thought he was not good enough for me, and was not free to give me enough. When he saw that I was not unhappy in Los Angeles when he could not come, then he did not even send me away during his final examinations.

Yesterday I saw him for a few minutes in his own house. He was alone. He prepared a drink with mint that he planted himself. How difficult it is to be together for only a little while. Such desire I have for him. He has a way of dropping his head suddenly on my breast, with such abandon. So happy I am today dreaming of our next trip together. He sent me far from here yesterday to buy a cookbook from the famous French cook Henri Charpentier, for our life in San Francisco where he will study forestry at Berkeley. He said, “When we amalgamate our libraries we shall have a system. I don’t think certain books should be mixed together.” At times he calls me twice a day. He calls me at midnight sometimes, when I am asleep.

I fear his adolescent Don Juanism, his need to charm and conquer, his pleasure in being liked. He teases me. And I feel him react to every pretty woman as he reacts to flowers, trees, music, skies—with enthusiasm. Yet I feel so fortunate to be deeply loved by him, that I want to have faith and courage. Great lovers never trust each other. I imagine him as impetuous as he was with me. He imagines me, no doubt, as impetuously responsive to others as I was with him. Strange life, strange boy, too. Few understand his whims and fancies as I do. Few, perhaps none, understand that his compassion for others means he needs compassion himself. He is vulnerable and requires care and warmth.

Every trip is an adventure, because we explore new realms of love. This one came after his final examination at UCLA when we knew we would not see each other for a week or ten days, and I suggested traveling with him to his summer job in Colorado. At the last minute I teased him: “Perhaps I won’t come.” And then he became anxious and fully aware of how much he wanted me to come. So again Cleo is waiting at the door and we are off.

The first night in Las Vegas, in the little motel room, our caresses became electrical and feverish, wild. He fell asleep murmuring: “The desert is good for us.”

Our lovemaking was like the desert heat, the hair-fine desert flowers, the sharp smells and the hot and warmed-toned sand.

Second night: again the hunger and fever.

Third day: we stopped by a river and took our clothes off. In the water he took me, floating and swaying, cool, lying on the shallow edge, and then he planted a tiny poplar tree by the place. So small and fragile, on the river’s edge, and I was afraid it would be carried away. Our bodies, our moods, our fevers, seem to fight for permanency. His acts moved me, like tender rituals. A poplar tree planted where we loved each other. I laughed and said, “I have met Pan.” I always wanted to meet Pan. He was wonderful. He came out of the river and took me. “You’re a water sprite,” he said.

Again a river. A very wide and wild one, the Colorado. Ice cold. But as we came out the sun was warm and Rupert bent me down on the sand and took me. But this time the cruel green flies stung us while we made love.

At dawn his soft, full mouth on my cheek. Before he opens his eyes he turns to embrace me.

Depression the last day. Cleo broke down. The wild and beautiful voyage was over. He put me on a bus, and although he had said, “This time you’re not unhappy, this time you know it will be a short separation,” I felt pain, pain at leaving him. When I arrived in Hollywood, in my room, I had the feeling of something torn from my body, this painful emptiness, his vivid face, his eagerness, his swiftness, his voice, his telephone calls at night. His warm, lithe body so kneaded with mine. The sensation of his slender body like a vine, all tangled with mine. Often during the trip he told me what kind of place he wanted me to take in San Francisco. How he would paint it, fix it up.

LOS ANGELES, JUNE 26, 1948

Dream: Bill is there. But there is an older woman, severe looking, who is always watching him like a nurse or a governess. She is without pity, never leaves us alone. I try to soften her by telling her Bill and I have been separated for two years and want to talk to each other, but she says she has been told to watch over us. Finally Bill and I manage to come close, physically, but he uses a red gel and we are not happy.

I think of Gonzalo as dead—the Gonzalo I loved is dead. The one I knew at the end, without illusion, I did not love. People create an illusion together and then it is disintegrated by reality.

So I am now writing a book about Gonzalo as he was and I began simply and humanly. It is my last act of love. It is the monument that he will not be able to destroy as he destroyed our life together.

Of the fragments I did, only a few survive. Nothing of what I wrote in Acapulco. Out of hundred pages only twenty are good. I am only beginning now to work seriously. I am lonely; I am hungry for Chiquito. It is a difficult moment. I have acquired a mood of economy, having spent lavishly and now atoning. I eat plainly and frugally. A discipline. An enforced asceticism. Bill is coming to visit soon. I do not want to yield to him physically. I want to be true to Rupert.

The feminine desire to espouse the faith of those I love, as I espoused my father’s and then my mother’s, then Hugo’s. I only swerved from each as my love changed. I swerved from admiration of my father’s values to those of my mother’s, from my mother to Hugo, Hugo to Henry, Henry to Gonzalo (with ramifications of each in minor terms). The curious fact is that I have returned to Hugo by way of Bill and Rupert, who are Hugo’s sons, physically, in build and race (Irish, Welsh, English), mentally and emotionally, men of responsibility and of certain repressions and rigidities in conflict with their emotional and wild natures, men of aristocracy and of certain conventionalism of principle, of kindness, of nobility and honesty. Quite far from Henry and Gonzalo, who were completely neurotic, false primitives, twisted men of nature.

Rupert is more like Hugo than any of them, except that in temperament he has less control over his natural impulses, but equal guilt and control intermittently, which causes a rhythm of expansion and contraction alternately.

At fifty, Rupert will be more like Hugo than like Henry or Gonzalo, except for the Don Juanism, which he has in common with Henry. But Rupert is a man of love, and Henry was not. With his great beauty he could have been narcissistic, pampered, beloved by all women and given everything, protection, wealth. But instead he remained sincere.

There was masochism in my relationship with Henry and Gonzalo, and their brutality and violence may have seemed like necessary elements of primitive life, but in my life today there is an aliveness of emotion, a keenness of sensation that does not need to seek danger, pain or violence to feel its aliveness.

LOS ANGELES, JUNE 27, 1948

In spite of all my machinations I cannot avoid these abysms in which I find myself as in Acapulco, without Rupert and without Hugo, and lonely. Alone with my writing. Alone at night. And never resigned, never able to live like this. I feel depressed, invaded by the past because my work forces me to remember, because it is the source of my stories, my life. If only I could always create out of the present, but the present is sacred to me, to be lived, to be passionately absorbed, but not transfigured into fiction.

The alchemy of fiction is for me an act of embalming. Bill, having been subjected to this process because of his two years in Korea, has lost a good deal of his human reality. What will I feel when I see him? What a hopeless relationship, due to his subjection to his parents, his childishness, his fears and submissions, guilts. What will he make of his life? Such a selfish love! He has never once written me when I asked him to, answered my cables when I wanted to visit him, never answering a need, complete passivity. And when he was staying with Frances Brown, if I called him up to ask him to come, he would rebel. All the rebellions he did not dare at home he dared with me.

Chiquito. When I came in February for our birthdays he said, “Friends have asked me: ‘How old is Anaïs?’ I had to say I don’t know. I don’t know and I don’t care.”

“Guess.”

“From all you have told me, not from your appearance, I would say thirty-two or thirty-three. If you said less I would believe it. But if you say more I won’t believe it.”

He seemed anxious as he looked at me. I laughed. At first I said nothing, but I assented to his guess and added a year or two—thirty-five. And we celebrated his twenty-nine years and my thirty-five gaily. I laughed at my fear, my tragic fear of discovery.

What makes me feel the right to love him is that he was hurt by his first love and by his second. The first was physically good but emotionally and intellectually bad for him (“She was stupid and boring—just a beautiful girl, that’s all”) and the second, hard and selfish. I knew I could love him better. He is so vulnerable, so easily hurt, so susceptible, so easily harmed by criticism. He needs reassurance, warmth, understanding. He is often inarticulate, stubborn. He is naïve and candid. He needs subtlety. He is emotional and soft.

Bill did not write me for five months. Did not answer my request for news. And then a letter of desire, not of love. “About love, I don’t know,” he wrote. “But I want you.”

As Rupert won me with a deeper love, warmth, humanity, he detached me from Bill. Bill observed the coolness of my letters, acknowledged that he deserved to lose my love. I did not have the courage to write him: “You have lost my love,” but I felt it. And I would choose Rupert who gives me so much.

I can’t be harsh with Bill because he is twenty, lost and confused. But I bless Rupert for freeing me.

Now Bill cables that he arrives July 15.

LOS ANGELES, JUNE 30, 1948

While Hugo is finishing his analysis and preparing to come July 16, Bill is on his way from Korea.

I work at the story of Gonzalo with mixed feelings of love and pity for the dream of Gonzalo, and a full knowledge of its death. I know how Gonzalo killed it, and I pity him. I have forgotten my torment. There is an enduring love for the dream, with a knowledge of its death. Henry must have thusly buried June again and again with misgiving because the corpse is illumined, as it were, alive by the light of our first illusion, and one is uneasy about burying it, doubting its death. I have remembered Gonzalo with feeling and also the torment of the last years.

LOS ANGELES, JULY 2, 1948

I am exhausted with writing and with the conflict of making a river bed for the flow of the diary so that it may not seem a diary, but a monologue by Djuna in The Four-Chambered Heart. Not yet solved. The diary cannot ever be published. How can it seep into the work, not as a diary, but as a Joyceian flow of inner consciousness? Last night I wanted to give up writing. It seemed wrong to make a story of Gonzalo. I felt the inhumanity of art. I thought of my story of Bill in Children of the Albatross. But it touched his heart. It destroyed nothing. The story of Gonzalo will be perhaps an inspiration of love, a gift to the world, the only thing born of our caresses. It may be its monument, its only enduring image.

Last night, hurt and moved by memories, I was a woman acknowledging the continuity of love. This morning I was an artist, but I had come to terms with the woman and said, “It must be sincere, it must be truthful.” And I worked gravely, sincerely.

I talked with Chiquito by telephone. I want to be with him. He loses nothing by remembrance. He is to me equally magnificent as a lover, warm, tender and interesting, though he had repressed his wildness and he is younger and less free, less asserted than was Gonzalo. In his eyes there are worlds and memories, depths he does not know. He is not harmful to me as Gonzalo was. He is undiscovered, unexplored, and not free, but it is all there, and he manifests it in music and in his love of nature, in his love for me.

Early awakenings, songs of birds, and a gentle sun, downhill to Musso, a hearty, masculine restaurant. Then writing. Rereading volumes 49 to 54.

I never told the truth in Children of the Albatross, an idealized story without the destructive part. Shall I go to the end this time?

One handles the truth like dynamite. Literature is one vast hypocrisy, a slant, deception, treachery. All the writers have concealed more than they have revealed.

Yet, I too do not have the courage to tell all, because of its effect on Hugo and Rupert.

It is not imagination; it is memory, memory that stirs in the blood obscurely at certain spectacles, a city, a mountain, a face. Some are like dormant animals, and atrophied memories, but others feel this extension of themselves into the past, and easily slip into other periods.

The idea of memory is very persistent. I think of it all day. I believe the blood carries cells down through the ages, transmitting physical traits and characteristics. They lie dormant until aroused by a face, a city, a situation. The simple explanation of “we have lived before,” of recognition and familiarity. Racial and collective memory also continues, forming the subconscious.

LOS ANGELES, JULY 6, 1948

Awaiting Hugo and Bill, but without feeling for Bill, only friendship. No feeling for him at all. He has harmed me so much, has given so little of himself. I am nearest to Rupert. I feel him in me, inside me. I can feel the pain, his efforts, his courage up there in the mountains.

Hugo I admire terribly, his courage and effort in analysis, his immense struggle to be happy and free.

Hollywood for me is palms, flowers, flaming eucalyptus, jacaranda, the sun on gleaming cars, slacks and gold sandals, beautiful men and women, but standard, nondescript. Natural beauty of hills, sea, fogs and mists.

A relief to be far from New York, from Gonzalo, enclosure and ill health. I have gained health here. I feel like Rimbaud, that I walked out of my madness, and away from my demon. I am happy, but lazy and uninspired.

Bill telephoned: “Hello! I am on my way to San Francisco. I will be going to the University of California for some courses.”

He had not tried to see me. He was not going to New York. He did not know I was planning to live in San Francisco. I said very casually: “I’ll be there this winter. We may run into each other.”

| July 15, 1948 | Bill Pinckard returns from Korea |

| July 24, 1948 | Los Angeles |

| August 1948 | Move to San Francisco with Rupert |

| October 1948 | Return to New York |

| November 1, 1948 | Albert Mangones |

| December 1948 | Acapulco with Rupert |