Читать книгу Dissidents of the International Left - Andy Heintz - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

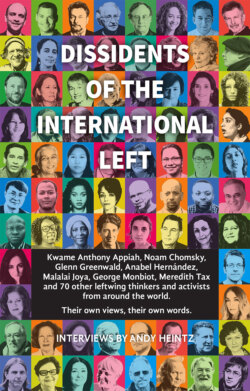

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

I began to write this book when George Monbiot – a man whose writing I had long admired – was kind-hearted enough to grant me an interview, despite not knowing anything about me other than that I was just some random guy with a vague idea about writing a book about the Western Left. It was the beginning of an adventure that took me to places and exposed me to new ideas that I had never before considered.

The original plan was to write a book focused on the divisions that had split the Left in the Western world. When I use the term ‘Left’, I’m using the word in its broadest sense, to include human rights activists, women’s rights activists, feminists, liberals, progressives, anarcho-syndicalists, democratic socialists and adherents of libertarian and democratic socialism.

I had been following the fragmentation of the Left in the West – mostly in Britain and the United States – from my hometown of Marshalltown, Iowa. One issue being vigorously debated that piqued my interest was: is there such a thing as humanitarian intervention? This question was subsequently followed by the question: is military intervention by the United States or some other Western country in another country justified if that intervention could prevent genocide, ethnic cleansing or crimes against humanity?

The split over this issue, which has probably always existed but hadn’t been given a chance to surface, was finally revealed when prominent members of the Western Left quarreled over the legitimacy of military interventions by NATO and other coalitions of Western governments in Bosnia, Syria, Kosovo, Somalia, Libya, Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq. While not completely agreeing with either group, it did seem clear that the US mainstream media would react to any invasion in the name of humanitarian intervention in a manner that was laced with selective amnesia, self-righteousness and double standards. However, the patriotic presuppositions and widespread acceptance of the narrative of American exceptionalism by the press didn’t seem like the only factor to consider when asking if military intervention was justified to stop the genocide and crimes against humanity being perpetrated by Serb-backed forces against Bosnian Muslims. After all, the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia that removed the Khmer Rouge from power and the Indian invasion of East Pakistan (modern Bangladesh) to prevent the genocidal atrocities of the West Pakistani army did objectively prevent further genocide and crimes against humanity, even if the reasons for the invasions were not entirely altruistic. The Vietnamese regime was guilty of human rights abuses in its own country and the government they set up after Pol Pot’s abominable regime fell was far from perfect, but it was still a hundred times better than the Khmer Rouge. India, meanwhile, might have intervened because of empathy for the Bengalis being systematically slaughtered, and perhaps because of worries related to the economic burden that came with accepting millions of refugees fleeing East Pakistan. I’m not telling people when or if they should support Western military intervention in certain cases, but I’m suggesting that one’s stance on this issue should not solely be based on whether the West’s motives are purely altruisitic.

I hope this book will also make it clear that, just because someone is critical of US foreign policy in Iran, Syria, North Korea or Libya, it doesn’t mean they are apologists for Bashar al-Assad, Muammar Qadafi, Vladimir Putin or the Iranian regime. One can be against arming the Syrian rebels, while still ideologically siding with the Syrian revolutionaries. In addition, one can oppose harsh sanctions on Iran because of the belief these sanctions will hurt ordinary Iranians, while still voicing support for the pro-reform and pro-democracy movements within that country.

Unfortunately, opposition to unthinking American exceptionalism has led some on the Left to embrace an inverted form of this doctrine that Meredith Tax has labeled ‘imperial narcissism’. This group, whom some have labeled the Manichean Left, have accepted the reductive notion that the enemy of my enemy is my friend and have minimized, rationalized or dismissed serious crimes of real and perceived enemies of the United States such as the Iranian regime, Putin’s Russia, Assad, or Serbia under Milošević. This ideology is irrational because instead of arriving at an answer after critical thinking where one attempts to be as objective as possible, these leftists – mirroring those whom they correctly criticize of ignoring or rationalizing US crimes – distort and bend the evidence available so it aligns with their ideological predispositions. Occasionally this group will make good points that perhaps elude other elements of the Left with different ideologies, but they will arrive at these conclusions through a way of thinking that is tainted by blind spots – and such blind spots can lead to future rigid and irrational views that turn the oppressed into the oppressors.

The early interviews I conducted with Monbiot, Bill Weinberg, Stephen Zunes, Stephen Shalom and Alex de Waal left much to be desired simply because of my own inexperience, and it is only thanks to their patience that I didn’t decide that I was in way over my head right then and there. My interview with Bill Weinberg was interesting, and life-changing. The veteran journalist expressed his displeasure with the American Left and said he was more inspired by feminists from the so-called Muslim world like Houzan Mahmoud, Karima Bennoune, Maryam Namazie and Marieme Helie Lucas. A lightbulb went off in my head that maybe instead of just interviewing members of the Western Left, I should interview left-leaning figures from around the world.

Maryam Namazie was nice enough to grant me an early interview and offered me names of other feminist activists such as Pragna Patel, Inna Shevchenko, Gita Sahgal, Yanar Mohammed and Fatou Sow. I researched these figures, and then I started sending out interview requests via email. To my surprise, they were all kind enough to grant me an interview. These interviews revealed some of my own blind spots, and I began to realize that there are problems other than Western imperialism that should also be confronted if we want to create a better world. I found myself gradually accepting the idea that, instead of focusing on just one problem rooted in injustice, it was necessary to critique, oppose and advocate against all forms of injustice simultaneously.

I made a conscious effort – although I didn’t talk to everyone I wanted to – to speak with people in regions of the world that are often depicted – by Western intellectuals who should know better – in ways that are Orientalist, reductionist and patronizing. This affinity for stereotypes can be seen when politicians describe the Balkans or the Middle East as places where groups have been fighting for thousands of years instead of understanding the conflicts in the region in their modern historical, political and cultural contexts. For this reason, I sought out interviews with Syrian intellectuals and journalists (Yassin al-Haj Saleh is one of the most brilliant men I have ever corresponded with), people from countries that were involved in the Balkan wars (Sonja Licht, Lino Veljak, Predrag Kojovic, Stasa Zajovic), and anyone I could talk to who had made contact with defectors from North Korea (Sokeel Park, Daily NK and Jieun Baek).

Lastly, I confess that my interviews with Michael Kazin and Michael Walzer changed my original opinion that patriotism could not be defined in a way that was worthy of support. I have been, and continue to be, a critic of conventional patriotism in the United States. I often perceive it as discouraging critical thinking and promoting tribalism on a national scale. But now I think Kazin and Walzer are correct that the Left in any country must have some personal attachment and relationship to its people, along with a positive, inspiring patriotic message that can be used to promote justice and equality both domestically and overseas. But – and this is a big but – this kind of patriotism would have to be acutely self-critical, intellectually consistent, self-reflective and fused with a spirit of international solidarity to avoid sacrificing important values in the name of pragmatism.

The book’s interviews are grouped by region but within each region the interviewees appear in alphabetical order.

Talking to leftwing figures from around the world has taught me that there are such things as universal values despite the rhetoric of religious extremists of all varieties.

At the end of the day there is no First or Third World, there is only one world. The sooner we accept this, the sooner we will have countries and a global system we can all be proud of. I hope the 77 interviews I have conducted via email, Skype and phone with leftwing figures from around the world can play a minor role in bringing the world we wish to live in closer to becoming a reality.

Andy Heintz

November 2018