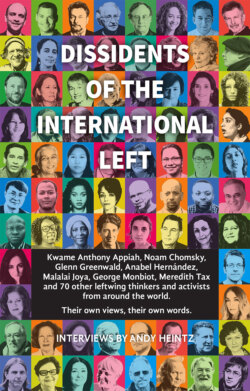

Читать книгу Dissidents of the International Left - Andy Heintz - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNOAM CHOMSKY

Noam Chomsky is a renowned linguist and arguably the most famous dissident intellectual in the United States. Chomsky has written an abundance of books deeply critical of US foreign and domestic policy, including Manufacturing Dissent, Deterring Democracy and American Power and the New Mandarins. Chomsky is frequently interviewed by mainstream and alternative media outlets the world over.

What do you see as the consequences of Trump’s climate-change denial for future generations? Does effectively combating climate change require international co-operation between nation-states, grassroots projects or a little of both?

It’s not just Trump. It’s the entire Republican leadership. It is an astonishing fact that the most powerful state in human history is standing alone in the world in not just refusing to deal with this truly existential crisis but is in fact dedicated to escalating the race to disaster. And it’s no less shocking that all this passes with little comment. Effective actions require mobilization and serious commitment at every level, from international co-operation to individual choices.

What are your thoughts on Trump’s rhetoric towards North Korea? What do you think would be a wise foreign policy to adopt towards North Korea?

On 27 April 2018, the two Koreas signed a historic declaration in which they ‘affirmed the principle of determining the destiny of the Korean nation on their own accord’. And for the first time they presented a detailed program as to how to proceed and have been taking preliminary steps. The declaration was virtually a plea to outsiders (meaning the US) not to interfere with their efforts. To Trump’s credit, he has not undermined these efforts – and has been bitterly condemned across the spectrum for his sensible stand.

What do you think US foreign policy should be towards Syria? And what do you think of Syrian dissidents who feel like much of the American Left has misinterpreted the origins as well as the complexity of the civil war in that country?

No-one has put forth a meaningful proposal, including Syrian dissidents – among them very admirable people who certainly merit support in any constructive way. Constructive. That is, a way that would mitigate the terrible crimes of the regime and the jihadi elements that quickly took over much of the opposition, rather than exacerbating the disaster that Syria has been suffering. Proposals are easy. Responsible proposals are not.

By now it seems that the murderous Assad regime has pretty much won the war, and might turn on the Kurdish areas that have carried out admirable developments while also defending their territories from the vicious forces on every side. The US should do whatever is possible to protect the Kurds instead of keeping to past policies of regular betrayal.

Why are the war in Iraq and the war in Indochina described by so many liberals and progressives as strategic blunders instead of as outright war crimes?

The same is true generally. Commentary on the Vietnam War ranges from ‘noble cause’ to ‘blundering efforts to do good’ that became too costly to us – Anthony Lewis, at the dissident extreme. And it generalizes far beyond the US. Why? It’s close to tautology. If one doesn’t accept that framework, one is pretty much excluded from the category of ‘respectabililty’.

What do you make of the criticism you received from liberals for comparing the consequences of the missile attack on the al-Shifa pharmaceutical plant in Sudan to the terrorist attacks on 9/11?

I wrote that the scale of casualties was probably comparable, which, as it turned out, may have understated the impact on a poor African country, unable to compensate for the effect of destroying its main source of pharmaceuticals. The consequences were radically different. Sudan didn’t launch a ‘global war on terror’. As for the criticism, I have also received criticism from Soviet apologists for accurately describing the crimes of the State they defend. Not quite an accurate analogy: such behavior is much more shameful in free countries where there are no penalties for telling the truth about ourselves.

You rarely use the term genocide in your commentary on foreign conflicts, including in your comments and articles on Bosnia, East Timor and El Salvador. Do you shy away from using this word because you believe it has been politicized?

I think that, if we use the term, we should restrict it to what I regard as its original intended use. Take El Salvador, with some 70,000 killed, overwhelmingly by forces armed and trained by the US. To call that ‘genocide’ stretches the term far beyond its intended use.

Do you think the estimate of 8,100 Muslim men and boys murdered in Srebrenica given by the International Commission for Missing Persons is correct, or do you think there are alternative estimates out there that are more reliable?

I’ve never had any position on the number of people killed, and simply take the standard estimates as plausible. I’m perfectly willing to leave the appealing task of intensive inquiry into the crimes of others (which we can do little or nothing about) to the great mass of intellectuals and would rather devote finite time to the vastly more significant topic of trying to learn something about our own crimes, which we can do something about. And even in these far more significant endeavors, I haven’t paid much attention to trying to assess the exact numbers.

Did any of the critiques raised by Diana Johnstone in her book Fool’s Crusade make you doubt the overall theme of mass rapes, mass executions and torture provided by refugees about the Serb-run concentration camps in Omarska, Keraterm and Trnpologe?

Johnstone discussed the way fragments of evidence were radically distorted and given extraordinary publicity as proof of horrendous crimes of enemies. That is the kind of work that is constantly done by intelligence services, human rights organizations and researchers who have concern for the victims and seek to unearth the truth. No valid questions have been raised, to my knowledge, about her discussion, which, as a matter of logic, has no bearing on the veracity of the refugee reports about the camps, including of course those she did not investigate.

Some critics interpreted your comments about Living Marxism (LM) as implying that the picture filmed by ITN television crews and featured on the front page of Time magazine of an emaciated man named Fikret Alic behind a barbed-wire fence was staged. Do you believe Doctor Merdzanic’s accounts of the nature of the camp, specifically that, while some people could come and go, others were prevented from leaving by armed guards?

Then ‘some critics’ should be more careful. There were reports that the photograph was misinterpreted, not staged – notably a cautious and judicious account, which I cited, by Phillip Knightley, one of the most highly respected analysts of photojournalism. Knowing nothing about Dr Merdzanic, I have no reason to question his account, or to comment on it. But it has no bearing on the LM affair and the shameful way a tiny journal was put out of business by a huge corporation that exploited Britain’s scandalous libel laws – also condemned by Knightley.

You have criticized Samantha Power’s widely acclaimed book about genocide. What is your main criticism of the book and why do you think it was so highly regarded by the mainstream media?

I didn’t actually criticize the book but rather its reception across virtually the entire spectrum of intellectual opinion. If someone wants to write a book about the crimes of enemies and how we should react to them more forcefully (without explaining how in any credible form), that’s fine, but it is pretty much more of the norm, of no particular interest. True, it was a little different in this case, and more welcome to liberal opinion, because the condemnations of the crimes of others were framed as a criticism of the West, and hence seem courageous and adversarial instead of merely conforming to the doctrinal norm.

What is of no slight interest is the enthusiastic reaction to a book that keeps scrupulously to crimes of enemies, ignoring crimes for which we are responsible, crimes that not only are sometimes comparable or even more severe than those on which attention is focused here but that are dramatically more significant for us in moral significance for a simple and obvious reason: we can do something about them, in many cases by simply terminating them.

Take one example, a particularly striking one. The book was written in the 1990s, during the final phase of what is arguably the most extreme slaughter relative to population since World War Two, by 1999 reaching new paroxysms of horror: the US-backed Indonesian invasion of East Timor. Power does not entirely ignore it. In passing, she criticizes the US for ‘looking away’ from the crime. In fact, Washington looked right there, intensely, from the first moment, providing crucial arms and diplomatic support and continuing to do so until the last moment in September 1999, even welcoming the mass murderer in charge (Suharto) as ‘our kind of guy’ (1995). Power’s predecessor as UN Ambassador, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, took special pride in his memoirs for having rendered the UN ‘utterly ineffective’ in reacting to the invasion and crimes (which he recognized), following State Department directives. So matters continued, with ample support from other Western powers as well, right into the huge new atrocities of September 1999, until finally, under substantial international and domestic pressure, Clinton quietly informed the Indonesian generals that the game was over and they pulled out, permitting a peace-keeping force to enter something the US could have done at any time. And to magnify the obscenity, that is now hailed as humanitarian intervention.

It may be comforting to become immersed in the other fellow’s crimes, joining in the general anguish, winning accolades and prizes. And serious investigation of these matters can be a valuable contribution. But it is immensely more significant – on moral grounds, in terms of human consequences – to unearth the truth about our own actions, to bring crimes to an end, and to internalize the lessons that will inhibit them in the future. ■