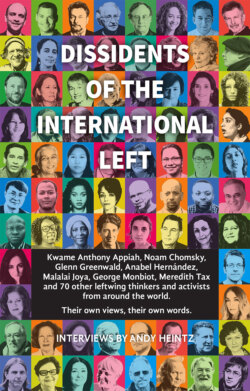

Читать книгу Dissidents of the International Left - Andy Heintz - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеKWAME ANTHONY APPIAH

Kwame Anthony Appiah is one of the world’s foremost philosophers on ethics, identity, ethnicity and race. Originally from Ghana and Britain, he now lives in the US, where he is Professor of Philosophy and Law at New York University. Among his books are: In my Father’s House; The Ethics of Identity; and Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a world of strangers.

How can cosmopolitanism triumph over rigid worldviews such as Islamic fundamentalism on the stage of global public opinion?

The appeal of malign fundamentalism begins with cultural resentment. It’s attractive to people who think their historical Muslim identity has been assaulted and beaten back over the last century or two by something they refer to as the West or Christendom. It’s similar to a broader pattern of the anti-imperial resentment that you find in much of the post-colonial world. It is a recognizable state of mind. In the long run, the only way for that to go away to is to make people feel like the identity, civilization or nationality they represent is doing well in a positive way in the world – and for that to happen, the situation has to change in many places. There must be real democracy in Pakistan, there have to be real jobs available in Egypt, and so on. People have to feel confident and positive about their situation.

Is the good Muslim-bad Muslim culture talk misrepresenting the other identities Muslims have?

Everybody has lots of identities: almost no-one is acting on just one of them all the time. It’s true that there are small numbers of people in the world who are motivated to do terrible things in the name of Islam, but it doesn’t follow that they are acting in the name of Islam – in the same way that if someone blew up a gay bar in the name of Christianity, that wouldn’t mean they were acting in a Christian way.

When someone acts in the name of something, it doesn’t follow that their act is justified by the religion or ideology they are referring to. Whatever explains the attitude of people who commit terrorist acts, it can’t be Islam, because if Islam explained it, there would be a billion people doing the same – and there aren’t. So, the fact that someone does something in the name of an identity doesn’t mean we can blame everybody in that group.

When people do bad things in the name of the US, we repudiate them and claim that that isn’t what America stands for. We don’t say ‘OK, we [as Americans] accept responsibility for that’. I don’t think Muslims should accept responsibility for people who have done terrible things just because they have claimed to have done it in the name of Islam.

Some people who have been vocal about the need for moderate Muslims to speak out against Islamic fundamentalism still defend the Iraq War and supported atrocious regimes in Central America, Southeast Asia and Africa during the Reagan administration. Is there a double standard at work here?

If we are going to ask people to repudiate things, we should be on the same page ourselves: there are a lot of things we might want to repudiate. There are two problems here. One is that there is disagreement in this country about which actions should be repudiated. As an American, I’m happy to repudiate the Iraq War, Guantánamo Bay, and so on. But there are people who think those things are OK.

Many in the US think that the conditions in Guantánamo Bay are fine, and the Iraq War was a mistake strategically, but not morally. A lot of people who think our assassination by drones is unlawful and the wrong way to deal with terrorism – they believe it shows a lack of respect for national sovereignty, and it causes a lot of collateral damage, killing innocent men, women and children. But most Americans are not going to repudiate drone strikes because they don’t think they are wrong. And even when Americans are forced to accept that we did something wrong, we’re not very good at repudiating it. We haven’t managed to get an American president to apologize for slavery, which ended in the 1860s.

Do you think some of the world’s problems derive from an assault on the autonomy of the individual? Could you comment on the attempts to place people into cultural boxes by claiming Asians have Asian values, Africans have African values, Westerners have Western values, etc?

In general, when you have politicized identities, people demand that members of their group agree with certain things they care about. But while some people do have things in common, if you take large categories like Asia, Africa, or the West, there is a huge amount of in-group disagreement. There are people who think Christianity is the truth and people who believe atheism is largely correct. But they are all Westerners, and you can’t say Westerners believe in something, say gay marriage, when there are anti-gay movements in America and France.

These large categories tend to be much more heterogeneous within than people recognize. Even if I am Asian, and even if there were such a thing as Asian values, it’s not obvious why I should be obliged to go along with them. I could think that maybe there are not many democratic traditions in Asia but I’m an Asian, and a Democrat. I don’t decide whether I should back abortion rights by taking a poll of my neighbors and trying to think about what the American view is, I think about the issue itself. It’s best to ask what’s right, not what’s traditional. In the conversations about what’s right we have a lot to learn, not just from our neighbors with whom we share an identity, but from everybody.

You have referred to Africa as a European concept. One of your criticisms of the Pan-African movement is that it was race-oriented and that it failed to recognize the multiple identities that all human beings have and the many differences between the societies that were located in the geographic space that Europe monolithically referred to as Africa. Can you expound on this subject?

Just as most Europeans were not aware of themselves as Europeans until a certain point, most of the population in continental Africa didn’t see themselves as part of continental Africa because they were unaware there was such a thing as continental Africa until sometime in the 19th century. They certainly didn’t know about what was going on in the rest of continent. They didn’t know about the traditions, customs and histories of the other people, in much the same way that Romanians didn’t know anything about the history of Denmark. So the term African became an important identity during the slave trade, especially during the 18th century. People discovered that this category was going to be used to determine their treatment. So by some time in the 18th century it became permissible in the Western world to only enslave people who were Africans.

Part of what happened is that Europeans started to think of Africans as one united person – as Negroes who had a sort of shared debt of properties and a shared essence. That idea made its way into African thoughts about politics in the 20th century largely through the thinking of New World Pan-Africanists, like WEB Dubois, who took these 19th-century American racial ideas into their account of how they thought about black identity everywhere. Now there is a debate about when Dubois became less racial in his thinking, but that’s just a question about one intellectual. The movement as a whole continued to make these assumptions about the natural uniformity of Africa because they assumed that all black Africans had something deep in common and that was a mistake. The deep thing they had in common was that they had all been victims of European imperialism and racism. ■