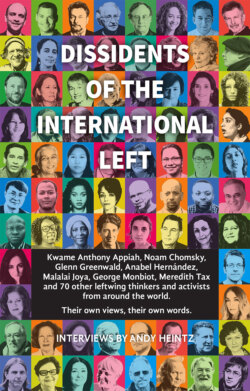

Читать книгу Dissidents of the International Left - Andy Heintz - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMICHAEL WALZER

JON FRIEDMAN

Michael Walzer is one of the US’s most prominent intellectuals and has co-edited the leftist magazine Dissent for several decades. He is the author of many books, including Just and Unjust Wars and What it Means to be an American.

What would you change about the international Left today?

Leftism is primarily a domestic politics. It has always been primarily a domestic politics. On domestic politics, we are pretty good. We favor greater equality, we favor welfare, we favor education, we favor State action on behalf of minorities, etc etc… Socialism at home is easy for the Left.

Internationally the Left has a very bad record. We have supported and apologized for tyrants and dictators and terrorists. We have failed to acknowledge the realities of the world we live in. Many European leftists opposed rearmament against the Nazis all through the 1930s. Appeasement was a policy of the English Right with a lot of support on the Left. We don’t have a great record.

So, I want an international Left that is alert to the realities of the world and honest in confronting them. Let me use the example of the Iran nuclear agreement right now. The Iran deal [concluded by the Obama administration] is, I think, a good deal but people on the Left are supporting it who know absolutely nothing about it, who aren’t interested in learning anything about it and who would support it even if everything the Republicans say about it were true… everything. That’s an irresponsible Left, and there are too many leftists of that sort. One international Left organization that I belong to but won’t name here circulated its statement in support of the Iran deal a month before the deal was signed, and a month before they knew any of the details of the deal. That is irresponsible. People on the Left have a great deal of difficulty imagining themselves in power and responsible for the wellbeing of their fellow citizens.

I want a responsible international Left with active, engaged citizens who are capable of recognizing the dangers of Nazism in the 1930s, the dangers of Stalinism in the 1930s and 1940s and the dangers of Islamism today. I want the international Left to criticize their government, but to also be aware of the dangerous world we live in. So, there is my soul exposed. I really hate those leftists who don’t think about the wellbeing of the people they claim to be acting on behalf of.

The narrative that all US wars are fought for our freedoms is widespread in American culture. What will it take to foster a culture where Americans can look at their history and say, ‘OK a couple of these wars were to protect our freedom, but most of them were not’?

We thought we were achieving that in the 1960s with the anti-war movement. We thought we were persuading Americans to look at an American war and say, ‘no, it’s wrong’. Obviously, we didn’t do that. I was very engaged with the anti-war movement. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, we organized a group called the Cambridge Neighborhood Committee on Vietnam, which did SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]-type community organizing against the war. We forced a resolution on the ballot saying the city of Cambridge was opposed to the Vietnam War, and we got 40 per cent of the vote. We carried Harvard Square, but we lost all the ethnic and working-class neighborhoods in Cambridge.

A sociology graduate student did a study of the vote and found that the higher the value of your house, the higher the rent you paid, the more likely you were to vote against the Vietnam War. We were losing the working class, and one reason was that we marched around with Vietcong flags, we spelled America with a K, and their kids were fighting over there and our kids weren’t. We were right to be against the war, but we opposed it in a way that alienated the very people we should have been trying to convince.

Do you think a better strategy could have convinced the working class to look more closely at American interventions?

You have to try to devise a strategy that evokes their patriotism against American crimes and I think that can be done. I think we could have done a much better job in the 1960s.

Does it worry you that the US military is the one group that is considered above scrutiny for a lot of people in this country?

You know, I wrote a book called Just and Unjust Wars that was adopted as a required West Point text by a group of Vietnam veterans who had been so shaken by the war that they wanted the cadets at West Point to read my book, which included a critique of the war. Because they are using my book, I sometimes lecture there, and I can tell you the officer corps of the United States Army is much more critical of US foreign policy than most Americans are.

They are critical of some of our wars. They are unhappy about the way we fight some of our wars because too many civilians are being killed. They hate the business of military contractors fighting alongside our soldiers. In Iraq we had as many military contractors as soldiers and the contractors were not subject to normal military discipline or justice. The military contractors killed people without any possibility of punishment.

I was once driven up to West Point by an Army colonel who said he had canceled his subscription to The New Republic because they had supported the Iraq War. The professional soldiers, because they have some sense of the honor of the military, are often critical about what politicians do with the army. They are committed to civilian control of the army, so they don’t challenge the government, which I suppose is a good thing, but they are often critical of what politicians do.

Do you think there is a need to discern the difference between physical bravery and moral bravery when it comes to how American citizens view the US soldier?

Most soldiers in most wars are kids and they have been told by their teachers and preachers and political leaders that the war they are going to be fighting in is just – and then they go, and they fight. It’s the grown-ups who have a responsibility to oppose the war. You can’t expect an 18-year-old kid in Vietnam to oppose the war. That was our responsibility.

Do you think progressives who supported the war in Afghanistan in the name of self-defense would also have to support Guatemalans, Nicaraguans and Cubans if they had used self-defense as a rationale for bombing American military installations because of US war crimes and US-backed terrorism in their respective countries?

Had the Vietnamese been able to manage an attack against American military installations here at home, that certainly would have been justified. It wouldn’t have been terrorism, it would have been war. We were at war and when you go to war you have to accept your own vulnerability to attack. And after the Cuban invasion that we sponsored in the Bay of Pigs, I guess a Cuban response directed at the places where we were training Cuban insurgents would certainly have been justified.

You have talked a lot about progressive solidarity. How should progressives try to establish solidarity with progressive forces in other countries like the Rojava Kurds, the Organization of Women’s Freedom in Iraq or the Local Coordination Committee in Syria?

You have to think first at the level of the Left and then what we want governments to do. At the level of the Left we should be providing ideological support; we should be providing political and moral support; we should be raising money for these groups to help fund them; if there was an international Left capable of this, we might be organizing an international brigade in some of these cases. Right now, the international brigades come from the Islamists, not the Left. Maybe Doctors Without Borders and Amnesty International are the contemporary international brigades for the Left. At least they defend life against people who are tyrants and terrorists who take life. That’s what the Left should be about: to give whatever support it can give.

There has been a lot of talk about Islamophobia in the press. How should progressives approach freedom-of-speech issues that are being put to the test by Islamic terrorist attacks? How do we discern Islamophobia from legitimate critiques of Islam, which, like any religion, should not be above criticism?

Well, you just said it. We oppose nativists in France or Germany or the United States who hate immigrants. The know-nothings of the 1840s and 1850s hated Catholics and now we have similar kinds of campaigns against Muslims and we have to oppose those types of campaigns. At the same time, we have to be ready to criticize Islamic fanatics. I think it’s no different from looking back to the 11th century and criticizing Christian Crusaders while acknowledging that Christianity isn’t necessarily a crusading religion.

The jihadist interpretation of Islam is one possible interpretation of Islam, just as the Crusader interpretation of Christianity was one possible interpretation of Christianity. But there are other and better interpretations of both religions and those are the ones we should be supporting. ■