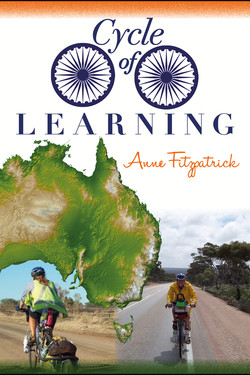

Читать книгу Cycle of Learning - Anne Fitzpatrick - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3: Nipple Confusion and Corporate Uniforms

ОглавлениеSydney – Ku-Rin-Gai Chase National Park – Berowra Heights – Wyong – Newcastle – Maitland – Gloucester – Taree – Kempsey – Nambucca Heads – Coffs Harbour – Woolgoolga

Totals: 3,557 kilometres – 204 hours 33 minutes – $4,847

Friday 18 March

Sydney, New South Wales

I spent nearly a week in Sydney, catching up with friends, eating ice cream and refreshing my library at secondhand bookshops. On the down side, I had just one school visit in this time. Another school got in touch to find out if Kodaikanal was affected by the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami. I cringed into the phone as I heard myself replying, “Unfortunately, no.” I paused and rephrased my answer. “Thankfully, Kodaikanal is a hill station about 200 kilometres from the coast.”

This school, like a number of others I had heard from, would have liked to support Cycle of Learning but was dedicating their fundraising efforts this year to victims of the tsunami. That’s the reality of fundraising, I suppose. There are so many causes and charities both here and overseas asking for support. The community has limited money and attention to give and people have to choose. There is no one to blame, but it gets disheartening when your cause is not being chosen. More disheartening was the fact I’d only raised a few thousand dollars so far.

The fundraising strategy I had been using was to notify as many schools, churches, community groups and media outlets as possible about my ride and its cause, and ask if they would like me to stop and speak to them. When I visited, after giving a talk and answering questions, I would leave them with information about how they could donate if they so chose. The Lutheran Church of Australia’s aid and development arm, Australian Lutheran World Service, had endorsed my project, and was processing donations and issuing tax-deductible receipts. I’d considered seeking corporate sponsorship before I left Adelaide, and tried approaching some companies, but the whole process terrified me and seemed to require a level of professionalism, self-assurance and persistence that I just wasn’t able to muster.

Financial self-pity aside, the school I did visit in Sydney made me feel important. After a tour with two school captains, I was escorted to a balcony from where I addressed the entire student body who were sitting below on the basketball courts. I felt a little like royalty greeting loyal subjects. If my fundraising strategy didn’t work out, maybe I could get a part-time job somewhere being a princess to raise the rest of the money.

After my balcony performance, I gave a more intimate reception to a group of student leaders from the senior school. I was glad to be able to touch on some of the more complex issues for young people in Kodaikanal, and share some other stories from Kodaikanal, including what Pandimeena shared with me about her life.

Pandimeena and the Grihini program

I work for PEAK as a nurse and am from one of the upper hill villages in the Kodaikanal Hills. About 20% of the people there are cobblers – a Dalit caste.

I am the first Dalit girl in the Upper Kodaikanal villages to finish Year 12, which I did in 1999. I was motivated to complete school by my elder brother who was the first Dalit boy in the village to finish high school. After I finished high school, PEAK provided me with financial and pastoral support to gain a diploma in Multi-Purpose Health Work. My parents, especially my father, were supportive of my training in nursing. I chose nursing because I remembered when I was a child how my mother suffered from chest pain.

I have worked with PEAK since 2001. I am in charge of the Mother and Child Health Program, which assists six Adhivasi villages in the lower Kodaikanal Hills. I also take care of the health needs of students at PEAK’s hostels, villagers that live nearby, and girls from the Grihini program.

I have seen first-hand the violence, exploitation and discrimination arising from caste issues in the villages. In my village, there are five dominant, so-called higher-caste, groups and one cobbler group. I have at times seen four families living together in one small house, with the result that the families suffer from many diseases.

At least half the Dalits in my village are dependent on the landowners who belong to the dominant caste. Because of this situation, the Dalits’ wages are very low and they are unable to educate their children. Once the Dalit boys finish Year 5 they are forced to tend the cattle belonging to the so-called higher-caste people. This is a form of bonded labour.

My vision is to get a further two years of training in a hospital, then start a clinic in my village. I would like my clinic to help my own community, which is poor and under-privileged.

I am particularly glad that as well as looking after the health needs of the girls in the Grihini program, I am living closely with them. These girls can be motivated by seeing what I have accomplished, and they, in turn, will educate their children right through high school.

This Grihini program that Pandimeena spoke of was the reason I first came to Kodaikanal. I’d been backpacking through India when a family friend, Norm, invited me to travel with him to Kodai, where he was visiting Grihini. In 1988, Norm, with his wife Jan, a Jesuit Father, Arokiam, and two teachers from a local school, Dency and Ruth, set up Grihini for local girls and young women from marginalised communities who were not in formal education. Grihini gave girls skills in health, income generation, literacy and numeracy, and awareness of social issues, as well as the tools to be part of social change in their villages and wider community by returning to their villages as “animators”, to educate others in health, hygiene, finances and liberative social action.

The 28 young women I met in the 2001 batch of Grihini welcomed me into their close-knit and vibrant fold. Most days I would make my way to their space at the back of Sacred Heart College, which, being on the side of the hills, was a secluded, grassed area with a handful of buildings opening onto it. A few girls might be in the open kitchen preparing the next meal on a big fire that needed firewood constantly fed into it. One room held most of the classes – literacy, or instruction on crochet or macramé basket-making. The writing slates or craft materials would be cleared away for tutorials on caste issues, human rights and gender. The girls would have debates, devise street theatre, sing awareness songs and meet Grihini alumni who were now working in their home villages to share awareness of health, hygiene and human rights.

Another room had a bank of foot-pedalled sewing machines for learning tailoring skills on. I could never figure the machines out, and was content to sit with a group on the floor sewing buttons onto shirts while chatter flowed around me. I gave self-defence classes to the Grihini group, one of the only skills I’d brought with me that had any potentially practical use there. It was a wonderful sight – seeing their strength and power physically manifest as we practised getting out of grabs, protecting from strikes and delivering punches, kicks, head-butts and eye-gouges. Without the kick bags I used in Australian classes, I made do with bringing the pillow down from my room for the girls to practise on. My plan for them to each bring their own pillow never transpired since, as I soon realised, the girls slept in the usual Tamil Nadu way – lined up in rows with nothing beneath them except the thin mats rolled out over the concrete floor of their classroom.

This constant togetherness – when at home being with family always, and in Grihini, continually in the company of their peers – contrasted sharply with my independence. The girls questioned me about the travel I had done and couldn’t get their heads around it. They liked the idea of seeing different places, but were baffled as to why I would do it by myself. It sounded like some sort of punishment to them.

The times I loved the most with the girls was Sunday mornings. It was their day off from study, and they took it in turns to bathe, wash their hair, and then sit on the side of the hill combing coconut oil through each other’s long tresses until they were glossy. A group of girls would make idli – steamed rice cakes – and a chickpea curry for the special breakfast of the week. Normally breakfast was a nutritious but plain bowl of rice porridge with a dab of lime pickle in it for flavour. These idlis had the girls grinning in anticipation, and they devoured serve after serve of the heavy cakes. They were making up for lost nutrients. Coming from families with limited access to health care or adequate food, these girls were small, underdeveloped and only one or two stood taller than my shoulder. When I met some of their parents who had travelled down for an agricultural workshop I saw what the future might have in store for these beautiful girls, so full of life and energy now. The parents seemed even smaller still than their daughters – scrawny and worn down from hard manual work in the home and fields. Even though the mothers would have had their children at a very early age, I initially mistook them for their grandparents. They had wizened wrinkled faces, gnarled and calloused hands, and a certain tiredness in their eyes, which I later recognised in the faces of some of their daughters when they spoke of a family member’s death, illness or abuse.

I don’t know all of the trials that these families had gone through. Some stories I heard from the staff. Female relatives that had been set on fire for not bringing a large enough dowry to the husband’s family. Siblings dying from asthma because the village had no clinic. Suicides to escape from shame or abuse. Parents tricked and betrayed in village politics. Family members beaten and insulted for their status as Dalits when accessing village resources.

For all this real hardship that they lived with, I felt humbled at the apparent eruption of grief they farewelled me with when it was time for my departure in December. Along with me, they were in tears, squeezing my hands and, in a regional show of affection, stroking the length of my face with a hand on each side, and then pushing their knuckles with a “crack” against their own heads. As I got in the jeep that was taking me to the bus stand, Vimala, one of the older girls who taught me how to dance, pushed something into my hand. It was the necklace she always wore, a heart-shaped pendant with green glass around it – a precious item for her, I knew, so I tried to put it back in her hand. She wouldn’t take it, and I left with that necklace as a physical reminder of what had happened in Kodaikanal. I came to Kodai thinking I could contribute something to needy people. However, for all my English speaking and first-world experiences, I had nothing to offer. Regardless, the Grihini girls, like everyone else I encountered there, bestowed me with friendship, affection and understanding.

Sunday 20 March

Ku-Rin-Gai Chase National Park to Berowa Heights, New South Wales

54 kilometres – 3 hours 42 minutes

Saturday marked my exit from Sydney. As much as I had enjoyed being in the hub of a big city and having easy access to friends and ice cream, I felt my lungs were asking for a break from all the car exhaust fumes I’d been inhaling. Bike and Trailer also seemed to be tired of being dragged up and down stairwells and getting caught in automatically closing apartment block doors.

We took the scenic route out of the city via the Harbour Bridge and caught a ferry across to The Basin in Ku-Rin-Gai Chase National Park. We stopped here for the night in a camping ground that had no showers, and was hosting what seemed to be a festive father–child camping event. I didn’t want to investigate too thoroughly though in case Bike or Trailer started feeling sad that they don’t have dads.

This morning I conferred with a ranger and some maps and planned a route through the national park. Just getting out of The Basin was a challenge however, since it ended up to be not so much riding terrain, but hauling Bike and Trailer up vertical inclines of loose gravel terrain. When we finally hit ridable road there was some ominous rattling from Trailer, maybe from the gravel cliffs or maybe from when he fell down some stairs getting off the Harbour Bridge the day before. Or maybe because of his father issues.

We kept riding, but I kept my ears open for any developments. Halfway through the national park, I heard a sharp “ping” not from Trailer but from Bike’s rear wheel, and discovered one of its spokes had snapped off at the base where it was attached to the rim by the metal rivet called a “nipple”.

Unsure what to do, I took the wheel off, ate some sultanas, and waited for expert advice. I knew this would arrive soon as the area was a popular cycling route for proper cyclists who ride fast and eat special energy bars that they store in the pocket on the back of their riding shirts. I was confident they would know more than I did about broken spokes.

I soon managed to ambush a trio of cyclists who didn’t seem too happy to be interrupted midway speeding down a hill. They reluctantly pulled over and I did my best to impress them with my recently acquired bike part knowledge. I informed the pack that I’d “broken a spoke, which I have spares for, but I don’t have any nipples.” “No WHAT?!” was the reply. I started worrying that the bike mechanics I’d befriended just before leaving Adelaide had played a nasty trick on me. After clearing up our communication difficulties, they told me to keep on riding, as there was a bike shop located close to the national park. I made it out of the park, found the shop and pointed out the spoke that had broken off inside “… this part here”. “You mean in the nipple?” clarified the bike shop owner and set to the complicated task of replacing the spoke with just the right amount of tension. I took a number of good lessons away with me: don’t think someone’s better than you just because they have a pocket in the back of their cycling shirt, don’t talk about nipples to strangers, and always break spokes near a bike shop.

I headed down a side road into a valley that, according to my map, had a camping ground in it. It was a careful descent as Bike and my pride still felt injured. Despite the extra care, halfway down, Bike’s rear wheel produced an exciting popping noise. This time it was a puncture caused by the tyre itself wearing through. I dismounted and walked us all down to the banks of a small river at the bottom of the valley. There was no sign of the camping ground that was clearly marked on my map, but there was what appeared to be an old, weathered sailor sitting quietly by the water smoking his pipe. (This pipe, plus his proximity to the water, was how I knew he was a sailor.) I followed my new resolution and refrained from any mention of nipples, but asked him if he knew a place to camp. He nodded and pointed his pipe in the direction of a walking track along the side of the river, which I followed and found a small campable clearing.

The sounds of the lapping of water on the bank and the occasional fish frolicking in the shallows were soothing background music as I patched the punctured tube and replaced the tyre with the spare I carried strapped on top of Trailer. I felt so relaxed that even when I realised I’d messed up my gears again, I just smiled and took it as a good excuse to plan a walk back up the massive hill we had come down that afternoon, instead of riding it. I’m sure some cyclists would eat hills like that for breakfast, but I’m quite happy with muesli and going by foot sometimes.

Monday 21 March

Berowra Heights to Wyong, New South Wales

95 kilometres – 6 hours 24 minutes

I spent nearly two hours this morning walking Bike and Trailer out of the steep valley where I’d camped the night before.

By the time we emerged from the valley, I decided it was time for Bike to do his job again, so I squatted down to look at his gears with new resolve. Somehow, by gritting my teeth and muttering “Imagine you’re Col, imagine you’re Col”, I restored the gears to their pre-valley, functional glory.

I had three schools to visit in Newcastle on Wednesday and plenty of time to ride the 200 kilometres there, so I hopped on Bike and headed north, not exactly sure where to aim for by nightfall.

The Pacific Highway route I took to get there was beautiful, with lush greenery and blue skies. Beautiful, but with a generous supply of wind, hills, and motorcycles. I sweated a lot and got repeatedly distracted by the regular appearance of bakeries.

Carbed up, I made it to Wyong. Following the town map toward a caravan park, I stopped off at a deli and discovered a large bag of very, very ripe bananas. They were six for $1 and came with a warning: “For cakes and muffins ONLY”. Ignoring the warning, I started dreaming of what I could create with these bananas and the just-add-water custard powder I’d purchased that afternoon, and about how I would eat this custardy, banana-y creation after a long, hot shower.

Discovering a “Manufactured Home Village” sign out the front of what was marked on my map as a caravan park, I asked around and was soon informed that it was not a caravan park for camping, but a place for people to live in manufactured homes.

Confused, I picked up my rotten bananas and cruised the streets until I found a petrol station to ask for directions to a “proper” caravan park. Following these led me to another Manufactured Home Village. The manager informed me that I wasn’t allowed to stay there either, unless I was retired and willing to book in for a lot longer than one night.

I began to suspect that my problems were originating from conflicting definitions of the term “caravan park”. I explained the concept of temporary accommodation, grass to put a tent on, and surrounding caravans in a park-like setting, and the manager gave me directions to another caravan park. “Go to the end of the street then go through the scrub to Johns Road.”

I got to the scrub and decided to stop there, before I found myself being the Manufactured Home Village Idiot. Feeling content at the good fortune of finding a secluded, free and pretty location in which to set up camp, I sat on a log, and opened a tin of baked beans for dinner. After the first bite, I realised I was covered in mosquitoes. I killed six with my first slap, put down my baked beans and set up my tent as quickly as possible, only stopping to flick massive orange and black spiders off my feet occasionally. It seemed that while my campground was entirely unmanufactured and free of retirees, it was, instead, full of over-friendly insects.

I managed to throw all my gear, my tin of baked beans and myself into the tent without spilling anything, and finished off my first course while squashing the few rogue mosquitoes that had snuck in with me. I was alone by the time it finally came to mix up a huge mug of custard and overripe bananas. I’m not sure if it would have tasted better after a shower. Somehow, being coated in a fine but visible layer of squashed mosquitoes, blood, sweat, old sunscreen, banana and bicycle grease, lets you enjoy a meal in a heightened, uninhibited way.

Monday 28 March

Taree to Kempsey, New South Wales

120 kilometres – 6 hours 6 minutes

I spent a few nights and a quiet Easter in Taree. I celebrated the holiday with what seemed to be a never-ending bag of carrots and a change in my choice of condiment. I had made liberal use of honey over the previous two months: in muesli, on banana sandwiches, and, whenever an inconvenient low blood sugar situation arose, taken straight from the bottle. As useful and tasty as it was though, I’d been considering my finances over the past few days, and decided to use a cheaper honey-replacement as part of a strategy to tighten my budget.

After my fact-finding trip to India the previous year, and then the necessary purchase of equipment, I started my ride with just a few thousand dollars in the bank for living expenses for the year. I also wanted to use any funds raised purely for the Kodaikanal trust fund, not for my own costs. My solution was to take up my mum’s offer to borrow some money from her when I inevitably ran out of my own savings. Sometimes I had no option but to pay for an unpowered spot in a caravan park, so food was the only area over which I felt I had any control. Unfortunately, I eat a lot even when I’m not riding around Australia, so I was going to have to target quality, not quantity. The cheap bottle of home brand golden syrup at a discount shop probably only saved me a few dollars compared to honey, but it did make me feel financially back in control.

I packed the rest of the carrots into Trailer and coasted further north along the refreshingly flat Pacific Highway and reached Kempsey by mid-afternoon. This gave me time to try to reduce my accommodation costs by visiting all four caravan parks in town and selecting the cheapest one at $11 for the night. For this bargain price, I enjoyed an impressive lack of facilities. It took me 20 minutes and a few trips to the front desk to procure a functioning shower, and since there was no communal barbeque, I had to eat raw zucchini and tomato with my cold baked beans.

There was also a visit from the local police. I don’t think it was for me personally, although I had been smelling a bit offensive due to recent experimentation in saving money by not owning deodorant.

When I was finally showered, fed, and not arrested, I settled down with my safety vest and a permanent marker I’d bought that afternoon in a flash of inspiration. I wanted to increase the exposure of Cycle of Learning to people I passed on the road, as they could be potential donors. I already had a fluoro workman’s vest that I wore for visibility whenever I was riding and, because I kept forgetting to take it off, quite often when I wasn’t too. I thought I might as well exploit my visibility and use the vest not just for safety but also for publicity.

Half an hour later, I had a vest covered on all available surfaces with the project website address and “CYCLE OF LEARNING” written in large black letters.

Tuesday 29 March

Kempsey to Nambucca Heads, New South Wales

74 kilometres – 4 hours

My target for the day was Coffs Harbour, 130 kilometres away, and a longer ride than I had attempted for a while. After spending a few hours in the Kempsey Library seeing to some correspondence and my blog, I made a late getaway. Once I was on the road though, I made good time thanks to a gentle breeze at my back and plenty of muesli energy in my legs. Fifty or so kilometres down the road, I stopped when I came across someone I am not sure whether to refer to as “a colleague” or “the competition”.

I realised that I had passed this man, Colin, the day before when he was on the other side of the highway but, assuming from his three-wheeled cart that he was selling ice cream, I had not stopped. If it had been any other day, this assumption would have led me immediately across the two lanes of traffic to buy a cone with one scoop of chocolate and one of mint. I was still in money-saving mode though, and felt the responsible thing was to find another three highway vendors to compare prices, so didn’t end up meeting Colin that day.

This time, when I approached Colin on the same side of the road, I got close enough to read the signage on the converted three-wheeled pram he was pushing and realised that no ice cream was involved. Instead he was walking around Australia to raise money for children with cancer. I stopped and we had a short chat on the side of the road. He was friendly, polite, and interested in my ride, but the more I talked to him, the more overwhelming my sense of inferiority grew.

Colin had spent three years planning his walk around Australia, completed a wide range of other fundraising activities previously and established a foundation for his cause. He had numerous corporate sponsors, a network of Lions service clubs, and what sounded like a team of staff behind him. In only the third month of his walk, he had already raised an incredible amount of money. Apparently, he had had drivers stop him on the side of the road to donate four figure sums to his cause.

I felt an unprecedented level of amateurness as I talked with him. I wasn’t even able to eat my golden-syrup-and-banana-pita-bread-wrap in a dignified way as I waited for Colin to finish fielding phone calls from his agent, who was setting up a parade for his arrival into Brisbane.

I rode away with a rotten feeling in my gut that had nothing to do with the cheap golden syrup that I was not at all enjoying. Colin represented everything that I was not and everything I had not done. My bike ride and speaking to small school groups and the odd church or Rotary club had been well within my comfort zone. Emailing places inviting them to invite me to speak was much easier than developing contacts and networks and pushing my cause into the public eye. Buying my own gear was less painful than approaching businesses for sponsorship and support. Waiting for donations was a lot more comfortable for me than asking for them.

My planning had been rushed and haphazard. I’d fitted it in between completing my studies and working part time. Depressingly, I reflected that I could have worked this year as a graduate teacher and probably saved more from my wage than I was going to make in fundraising.

The heavy feeling in my stomach travelled down to my legs and I ended up finishing my ride for the day earlier than planned. I pulled over at a supermarket in Nambucca Heads and bought a large bottle of turpentine. I spent the evening trying to remove the black marker that I’d graffitied over my vest last night. Did I mention that Colin was wearing a nice, neat polo shirt embroidered with his logo and catch phrase “Dream. Believe. Achieve.”?

After an hour of soaking, scrubbing and rinsing, the writing on my own corporate uniform was faded but still visible. The vest was now scruffy enough to be even more unprofessional, yet legible enough to indicate which charity never to donate to. Plus, it now stank of turpentine.

Friday 1 April

Coffs Harbour to Woolgoolga to Pacific Highway, New South Wales

71 kilometres – 3 hours 55 minutes

I soon learnt to leave my vest outside my tent, after spending Tuesday and Wednesday nights haunted by unsettled sleep and bizarre dreams brought on by the turpentine fumes. I tried to brighten myself up by going on a sightseeing trip to Muttonbird Island. It didn’t work, as I spent the excursion plodding miserably through the rain across a scrubby island that was a good match for its grey, greasy, old-sheep name.

However, nothing cheers me up more than fruit, and after the morning’s stop at the Big Banana on the way out of Coffs Harbour, I finally started feeling a bit better. Even my rain-soaked bike seat stopped bothering me as I rode north, admiring the plantations of normal-sized edible bananas lining the highway.

The town of Woolgoolga improved my spirits further and pushed all concerns of mediocre fundraising performances and stinky vests from my mind for the majority of the day. The school I visited was in a beautiful location: the sound of the sea drifted through the grounds, and there were stunning views of rolling grassy fields and woods right down to the sparkling Pacific Ocean. The idyllic setting permeated the entire school with teachers and students relaxed and friendly in a way that is only possible when you’ve got a view of the ocean from every part of the property.

I was thrilled to discover that Woolgoolga is home to a large Indian community and a beautiful Sikh temple. This meant that among the students there was a lot of knowledge about Indian geography, languages and culture.

After lunching on piles of fresh bananas and crunchy watermelon next to the ocean, I stopped by the home of the editor of Australian Cyclist magazine. After an interview and a cup of tea, she generously gave me a copy of a book that I probably should have invested in a year ago: Around Australia by Bicycle. Now, if I could just find an edition of How to Gain Media Attention and Be in Demand as a Guest Speaker and Raise Huge Amounts of Money and Fix Gears and Eat Honey (or Golden Syrup) Without Getting Sticky in a light paperback version with easy to follow diagrams …