Читать книгу Cycle of Learning - Anne Fitzpatrick - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеIn 2001, after almost a year of backpacking through Asia, I found myself in the Kodaikanal hills of Tamil Nadu, India. Most of the people who unload from the buses that start in the plains and then zigzag through the hills to chilly Kodaikanal town are tourists from around India. Honeymooners in particular come for the very un-Indian cool climate, views of green, unlittered hills, pony-rides and home-made chocolate, and for the chance to take a row boat out onto man-made Kodai Lake (something that probably seems more romantic in theory than the splashy, hard-to-steer, ill-fitting life-jacket reality).

Marker showing location of Kodaikanal region in Tamil Nadu, India.

This town of Kodaikanal, or “Kodai” as it is often referred to, is named after the region with the same name in which it lies – a chain of hills with over one hundred villages tucked into its pockets, some close to the zigzagging roads, some in places so remote that they are almost impossible to reach.

The Kodaikanal area has been settled for thousands of years and, in recent centuries, been subject to waves of immigration. Pulaiyairs and Paliyars, known as Tribals or Adhivasis, are considered the indigenous people of the area. Adhivasis make up about 8% of the population of India. As other groups moved into Kodaikanal, the Adhivasis were forced from their traditional lands to poorer quality lands. Without the land or capital they needed to be self sufficient, many Adhivasi families were forced into virtual slavery as bonded workers on plantations. Generally, they have been paid very low wages, sometimes being paid in kind, such as with poor quality rice. A large proportion of adult Adhivasis are illiterate, live below the poverty line and have had little or no access to government assistance. They are outside the caste system that still operates in India, particularly in the rural areas, and therefore have limited access to economic, political and social resources.

Dalits (a name that means “the oppressed” – a term chosen by the community themselves, instead of the names given to them by others, such as “untouchable” or “outcaste”) are also outside of the caste system and another group of highly vulnerable people in Kodaikanal. Within the Dalit communities, there are those of higher and lower status. Low-status Dalits, known as Maadharis, constitute about 25% of the population in Kodaikanal hills villages. A high proportion of Maadhari people are illiterate and children are often sent out to graze the cattle of higher-caste people, which means they miss out on an education. Dalits have historically performed the most menial and degrading jobs, including agricultural labour, disposing of dead bodies, and cleaning toilets and removing sewage. Higher-caste people traditionally regarded Dalits as a source of contamination, and Dalits have therefore at times been segregated and denied access to many community facilities, such as schools, temples and water tanks. In India there are approximately 240 million Dalits – almost 20% of the population. Their long-term oppression has resulted in many Dalit communities being caught in cycles of extreme poverty and a lack of opportunities.

I spent three months in Kodaikanal, as a guest of a program that works with the Dalit and Adhivasi communities of the area: People’s Education and Action in Kodaikanal (which comes to the latitudinally-relevant acronym of PEAK). PEAK is a program that aims to provide opportunities in education, vocational training, health, finance and activism that will empower Dalit and Adhivasi communities to be able to step out of the cycles of poverty and oppression that have marginalised them for generations.

I spent most of my time in Kodai with the staff and students of two projects that PEAK has involvement with: Grihini, a residential training centre for young women, and Liberative Education for Adhivasis and Dalits (LEAD), which provides hostels and support for primary and secondary students.

The Grihini program, at that time, was a six-month residential course designed to equip illiterate and disadvantaged young women, who are often the most vulnerable members of their communities, with leadership and life skills in order to improve their own and their communities’ health, social, economic and political standing. Participants in the course were girls who had only attended a few years of primary school, if any school at all.

Participants came from the Dalit, Adhivasi and Sri Lankan repatriate communities in the Kodai area. Graduates of the Grihini program moved into roles running the program and staffing the LEAD hostels.

The LEAD program concerns itself with the formal education of Adhivasi and Dalit children, mainly through three hostels run exclusively for underprivileged children who are attending school. Two hostels are co-educational and cater to primary students (up to Year 5) and one is for high school-level boys (from Year 6 to Year 10). Girls continuing through high school stay in a hostel run by a local convent, with on-going pastoral support from the PEAK program. The first primary hostel, which started in 1991, began with 30 children; by the time of my first visit 10 years later, the numbers had expanded to 140 young people.

The hostels focus on literacy and numeracy, communication skills, development of leadership qualities, organisational and problem-solving skills, critical social and political analysis skills, banking and saving knowledge, physical education, agricultural skills, and exploring the role of young people in justice campaigns and organisations. The children are also given the opportunity to participate in games, singing and dancing, cultural events, sport, and their traditional religious observances.

As more students have continued through primary and lower secondary school, a need for higher education has arisen. Senior high schools, colleges and universities are geographically and financially difficult to access for the young people of the Kodai hills. In 2001 when I visited, PEAK supported a few students to continue their studies, but the funds for regular and ongoing financial support to a significant number of students was not available in PEAK’s budget.

Sacred Heart College, Kodaikanal, where PEAK has its headquarters.

This issue was on the mind of Father Kulandai, PEAK’s director, when I visited for a second time in 2004. I had come to sound out my cycling fundraising idea with the PEAK team.

One afternoon I was sitting with Father Kulandai, overlooking the sports field that the students from one of the primary hostels were playing on. Never enjoying conversations about money, I broached it rather awkwardly: “Hypothetically, if I could raise some money for PEAK’s work here, what would you use it for?”

Father Kulandai digested the hypothetical offer as quietly and serenely as he does most things. It didn’t take long though for him to come to a decision. “A trust fund. We need a trust fund for our senior students.”

Father Kulandai had it already thought out: with capital of the equivalent of $200,000, this amount could be invested in a long-term, secure bank account as a trust fund and the interest be used to help fund the secondary and tertiary students’ education. It would be an ongoing, sustainable and reliable way to fund an incredibly important investment in the communities of the Kodaikanal hills.

I had already done my calculations too, and informed him that I thought I could maybe raise a quarter of that – $50,000 – by riding around Australia and speaking to schools and community groups along the way. I admitted that I had an inherent aversion to fundraising, and knew my skills in marketing and publicising myself were wanting. However, I was so excited by the way that PEAK worked through education and activism, and felt such affection and admiration for the young people I met in their programs, that I felt, in a year, if I could talk to enough people, and share enough stories about PEAK and the people they worked with, $50,000 might show up.

The rest of my time in Kodaikanal was spent collecting the stories of young people in PEAK’s programs and gathering information from Father Kulandai and other members of the PEAK team. I returned to Australia with notebooks full of the interviews and facts and figures – and a small knot of responsibility in my stomach, now I’d made a promise to people and a cause that I had overwhelming amounts of respect for.

With a small group of friends who knew enough about the worlds of fundraising, development and communication, and enough about me and what I was and wasn’t capable of, some goals for the endeavour emerged. First, to raise money to help establish a trust fund for higher education for disadvantaged young people in the Kodaikanal hills. Second, to raise awareness with Australian students about the social issues faced by young people in India and the role that education can play in overcoming disadvantage. And lastly, to promote bike riding as a healthy and ecological means of transport.

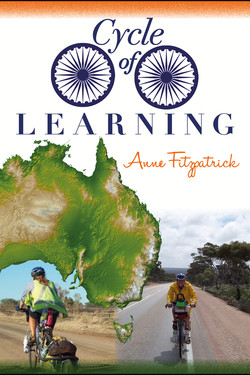

Christine, the most dexterous with words of the group, christened the project “Cycle of Learning”. And with a name, the hard work began.