Читать книгу Cycle of Learning - Anne Fitzpatrick - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2: Dirty and Altitudinally Challenged

ОглавлениеMelbourne – Bonnie Doon – Benalla – Albury – Jindera – Walla Walla – Walbundrie – Culcairn – Morven – Holbrook – Tarcutta – Bookham – Canberra – Goulburn – Wollongong – Bundeena – Sydney

Totals: 2,537 kilometres – 144 hours 16 minutes – $4,197 raised

Sunday 20 February

Bonnie Doon to Benalla, Victoria

73 kilometres – 3 hours 39 minutes

I learnt a lot in the past two weeks – how to outride flies, how to eat and ride at the same time, and how to go to sleep with dirty feet – but yesterday showed me I still have some troubling gaps in my cycling know-how.

In the morning I farewelled Diane and Neil, the hospitable second cousins I had met for the first time only the evening before, packed my bags and headed for the hills. These lasted a long time but weren’t too steep, and there was lush national park and forest around to take my mind off my legs.

I was feeling rather sunny and happy with my crew. In the kilometres from Adelaide to Melbourne, Bike, Trailer and I had settled into a functional working relationship and I was happy that I chose them as my travel companions. Before I left Adelaide I’d received all sorts of conflicting advice from cycling aficionados about the fancy, complicated equipment I would need. I ended up using a simple criterion for selecting my purchases: cheapness. I was lucky enough in August to meet someone who could help me distinguish between bad-quality cheap and good-quality cheap. I first encountered Harley, a raw-vegan anti-establishment ultra-athlete, working in a bike shop and he took me under his wing, psyched me up with his raw-vegan anti-establishment ultra-athletic philosophies, and led me around the displays, telling me quietly: “You won’t need that; you won’t need that; this bike is cheap but will get you round the country; you can get that cheaper on the internet; you won’t need that …” I left as a vegetarian, with half of my savings intact and a hope that ultra-athleticism was contagious.

True to Harley’s word, Bike and Trailer were doing a fine job. Although not ridiculously lightweight or high-tech, they required minimal attention and kept me trundling along. Trailer was easy to pack and with its single wheel following directly behind Bike, I hardly felt the weight of my sleeping bag, food, paperwork, clothes and small range of tools that I didn’t entirely know how to use.

While Bike marked a substantial improvement comfort-wise from the cheap, poorly-constructed bicycle that I used to own, my body was taking some time to adjust to life on the road. The first few weeks of riding were painful – in my shoulders, wrists, back, neck, legs, bottom, head, forearms, and in a spot that’s near where I think my pancreas lives. I had been warned about this by other cyclists – the soreness in general, not specifically in my pancreas – but also been assured that the pain would disappear after a fortnight or so in the saddle. They were spot on, to the day almost, and by the time I was crossing the Great Dividing Range the day before, I was feeling fit and comfortable. In fact, that whole morning I had an all-pervading sense of self-assurance with the performance of my body and equipment that was probably on the smug end of the confidence spectrum.

Prior to my departure from Adelaide I had a decent level of fitness, though not quite enough or the right sort of conditioning for this sort of ride. In its place, I had a confidence in my body assuring me that I could rise to and withstand whatever physical challenges came my way on the journey. This confidence came from the ten years of martial arts training that had been a huge part of my life since I stepped into my first class when I was 15. I had trained in wrestling, capoeira, a month each of Thai krabi krabong in Bangkok and traditional karate classes in India, and the bulk of my time in a club that practised a mix of karate, judo, jiu jitsu and weaponry.

This training had given me a multitude of rewards. Through it I learnt how wonderful it is to hone skills with repetition and focus, how to teach others, how something comes alive in you when you find what sparks your passion, and what an amazing tool and instrument the human body is. I learnt that my body was not something to be ashamed of for not looking as skinny or pretty as some parts of society suggested it should be. Why be ashamed of a body that can kick high, kick hard, kick with balance and timing and accuracy? Why be embarrassed by a body that can choke and armlock and throw another person? Why doubt a body that can be picked up and driven into the mats with a crunching wrestling drive, but knows exactly how to tense up and land safely so it can jump up and do the same back to its partner? Why not be proud of a body that can figure out how to do one-armed cartwheels, manipulate nunchucks, staff and sword, and fight round after round of sparring, boxing, kickboxing, throwing and grappling?

This is the confidence that martial arts gave me. I knew from experience that my body could refine technique, build strength in new muscles, ramp up its fitness levels and adapt however it needed to ride me around Australia.

In the early afternoon, I hit my usual post-lunch lethargy. Strangely, it didn’t disappear after a while as it normally did. Instead, I seemed to be moving progressively slower and slower. I thought it could be the fault of one of the small apples I had eaten from a tree by the side of the road. So, to test the hypothesis, I ate another one from the next tree to see if I felt worse. I did feel worse but not in a poisoned way, so wondered if I just needed even more energy. I ate some almonds and followed them up with a mouthful of honey, but was still struggling, so next I tried drinking lots of water.

I decided my body wasn’t to blame, and became more frustrated because, by my evaluation, I was riding downhill and should be going more than the 10 km/h I was. Once I checked for a puncture. Another time I stopped to see if a dead snake was caught in Bike’s chain. I’d narrowly missed running over three already that day, and one dead wombat. I figured, though, that a wombat would be too fat to get caught, so didn’t bother checking for one of those. As the absence of snakes cast no light on the situation, I gave up, dismounted and started pushing Bike and Trailer along. I looked over my shoulder to check for traffic that may think me soft, and realised I had actually been riding uphill for the past five kilometres or so. I know I have a bad sense of direction, but there is something odd going on when I can be on a hill and not know if I am going up or down it. Around Australia suddenly felt like an incredibly long exercise and my position on the confidence spectrum slid swiftly to the bottom of the chart.

This morning it was only a short ride to Benalla and the idyllic scenery kept me distracted from over-analysing the gradient of the road. I passed fluffy sheep eating the grass on the hills, flocks of birds, clear blue lakes, and children being towed behind speed boats (in a recreational, fun, non-abusive way).

Tomorrow I would ride out of Victoria. I had made it through the state in less than two weeks. Thanks to minimalist results in the school-booking department, I had pushed through the quiet countryside at a steady pace with Geelong as my only extended stop. It was worrying me that a state with such a significant proportion of Australia’s population wasn’t interested in me; or rather, that I hadn’t captured any interest.

There was not much to do though, but keep pedalling and hope that some better marketing skills developed along with my leg muscles, or that I would become more interesting the further I got from home.

Thursday 24 February

Albury to Walla Walla, New South Wales

52 kilometres – 2 hours 53 minutes

This morning’s dark 6 am start for a high school in Walla Walla provided me with not only the chance to use my beloved three-function headlamp but also to ride through a breathtaking sunrise as I went up and over the Jindera Gap. I spoke during an assembly which was themed “How much stuff do we need to be happy?” I was tempted to base my talk on the fact that everyone needs a three-function headlamp to be truly happy, but instead shared some of what I had observed during my time in Kodaikanal.

On the one hand there is definitely a lot of “stuff” that most of us have in Australia that families around Kodaikanal happily do without. On the other hand, there are things that, through poverty and social inequality, some families miss out on: easy access to clean water, adequate nutrition and health care, the opportunity to go to school, political rights and, quite often, three-function headlamps. These aren’t luxuries, but things that everyone should have the right to.

Wary of the fact that I was not an expert in Indian sociology, poverty or development, I tried to base the majority of my talks on information given to me by the PEAK team and on interviews I conducted with students when I returned to Kodaikanal for the second time.

Return to Kodaikanal

For this fact-finding return visit I navigated the Tamil Nadu trains, buses and sweet shops to retrace my steps back to Kodaikanal where the women wear fragrant strings of jasmine in their hair; men enquire after your “good name”; children either stare with horror at you or laugh with bewilderment; you get asked “You came here alone?” with a certain tone of disapproval, and “The food here is very pungent, yes?” with a certain smugness; and the hilly location means it is cool enough to not be sweating all the time as you do in the plains.

At Sacred Heart College, PEAK’s headquarters, I was welcomed once again into the ill-defined role I had occupied three years previously: something between a student, a nun, a man, a tourist, a visiting academic and a performing monkey. As there were grains of truth in a few of those, I couldn’t complain. I caught up with fatherly and brotherly friends of the Roman Catholic persuasion, and was warmly welcomed by the children in the hostels again. True, this was mainly due to my skills of pretending to eat imaginary head lice, killing real ones the kids brought to me, owning a watch with a button that lit up the screen, and singing my limited range of Tamil songs – but I still felt welcomed.

My lateral neck muscles reawakened to assist with at least 80% of my communication. I have considered compiling a phrase book with instructions for the head wobbles with meanings from “Yes, I’d love some more fried congealed goat’s blood with my rice” to “Thanks for asking. My diarrhoea is now painful but not inconvenient” to “Good morning. Yes I am a strange white person walking through your village” to “Mm, that was a tasty head louse”.

I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect when I began conducting interviews with hostel students. With the help of staff with translating, I collected a range of stories revealing the students’ love for their villages and families, the conditions their people live and work under, their hopes for the future and their feelings about living away from home and studying in the PEAK hostels.

A few students became upset while they were telling me about their families. Obviously, the children in the hostels love their families and miss them dearly. Talking about their father’s illness or the abuse their family has suffered through caste discrimination brought some to tears and others close. Hearing the children speak about their hopes for the future was a mixed experience for me. Nearly every young person I interviewed had grand dreams: to become a teacher, become a doctor, get a job with the government, teach and heal their people, and free them from the suffering that exists in their villages now.

The reality, however, is that while some of these students will continue their studies and maybe finish high school and maybe go on for further training and maybe have the career that they dreamed of, many of them won’t. Family needs will bring many of them back to their villages to work alongside their parents as coolies. Tradition often calls on girls to get married in their early teens, bringing their chances of formal education to an end. In school and college exams, these students are competing against students from literate families with uninterrupted schooling and more resources. Only a tiny proportion of the cost of education, particularly past the high-school level, can be met by the Dalit and Adhivasi families. So when the PEAK team put forward the idea of establishing a trust fund for the ever-growing number of students that finish primary school and are ready to go on to high school and beyond, I felt so excited at the thought that Cycle of Learning would contribute to something that would be sustainable, on-going and meet a real need for the people of the Kodai hills.

Back in New South Wales, I finished my talk and rode out of Walla Walla. A few minutes down the road, my Albury host – my godmother Maureen – pulled up in a ute and we surreptitiously hauled Bike and Trailer into the back to return to Albury in time for another round of school visits that Maureen had lined up for me. Not only is Maureen a fantastic godmother, she is also a hurricane of organisation and action.

I arrived in Albury on Monday to the reception of Maureen and her brother Philip (Mum’s cousins) and his wife Marie sitting on Maureen’s front fence cheering me in. Before I even had my gear out of Trailer, Maureen was on the phone lining up appointments with schools, church groups and newspapers. During most of the phone calls she made some sort of connection with the person on the other end of the phone – “You’re a Cunningham are you? Is your family from Corowa? Oh yes, my son Steven has been shearing in Culcairn with your father.” She gave a masterclass in networking.

Maureen is one of the people I admire most. She’s interested in everyone and everything she encounters, and if she notices any situation that needs someone to do something, she’ll be the person to do it. A few years ago she came across some newly arrived Bhutanese refugees who lived nearby and set to giving them all driving lessons. There was no one to do the church bulletin, so she taught herself how to use the computer software and now puts it together every week. When she visits her sons’ homes she’ll busy herself with cleaning out the fridge or doing some ironing (whether they want her to or not). She visits her mother in a nursing home every day and usually ends up spending a few hours feeding other residents, helping organise entertainment and popping in on people who need some company. Keep in mind Maureen’s mum is close to 100 and Maureen herself is 72. And chose to go skydiving for her 70th birthday.

On her trips to visit my family in Adelaide, Maureen starts chatting to people wherever we take her. She came down once for a wrestling competition I was in. I had spent the morning being intimidated by all the fit, muscly interstate wrestlers milling about waiting for their rounds. Within half an hour of Maureen’s arrival at the stadium, she had got to know a dozen or so of the competitors, and decided to barrack for Bill from Melbourne (one of the more handsome, less cauliflower-eared wrestlers in our vicinity) since he had the same name as her late husband. Whenever I’m in Albury with her, given she’s friends with a significant proportion of its population, a trip to the shops will involve stopping every few metres to say hello to her librarian’s daughter’s acupuncturist, or whoever it is that she knows.

I’m pretty sure if a neurologist did a scan of Maureen’s brain, the huge overdevelopment of “thinking about other people” region would be shown to have strangled out the “self-conscious” zone. She’s the sort of open woman who if conversation turns to dentists she will pull out her false tooth to give you a look, or after having a run-in with a sheep on one of her son’s farms, she’ll drop her trousers to show you the bruise she’s got on her thigh.

She is one of the best examples I know of how to live a happy life. We had a conversation once about depression. Maureen told me that while she felt really sorry for people who suffered from it, she found the whole concept completely confusing. “Why don’t they just go out and talk to people, or do something interesting … ?” Maureen has the balance right – by spending her time thinking about others and acting on their needs enthusiastically and unreservedly, she’s eliminated the parts of her thinking that cause suffering to a lot of the rest of us. Ego, insecurity, self-centredness and disconnect from others do not get a look-in on how Maureen functions.

On the way back into Albury, as we barrelled through farmland with brown crops and receding dams, I saw two figures on bikes in the distance. They looked familiarly fast and unfriendly. As we neared the cyclists with their matching panniers, my suspicions were confirmed. They were the two Danish riders who had passed me on the way to Meningie two weeks ago. Maureen wanted to stop and talk to them of course, but as my pride was still wounded, I insisted that we drive past and not disrupt them from their fast and focused cycling. Ego and social disconnect is particularly hard to rid yourself of when it comes to being ignored on the road.

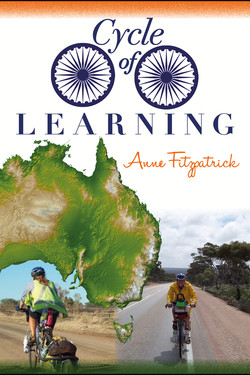

With Bike and Trailer on the New South Wales coast.

Saturday 12 March

Bundeena to Sydney, New South Wales

39 kilometres – 2 hours 31 minutes

In the past few days, I came to realise that there are some things I cannot do, and some places a bike should not go. The day before, Macquarie Pass earned a place high on the list of the latter. I had a few route options to get to Sydney, but this one had nice-sounding roads and towns, and the route – on the map at least – looked easy enough. There must be better criteria for navigational decision-making but I was yet to figure it out.

I began the morning meandering down the Illawarra Highway reflecting on the students I’d spoken to in a Goulburn primary school. They had listened politely to my spiel about India, discrimination, education and social change. I had my enlarged laminated photos of Kodaikanal ready for question time, but the kids immediately homed in on my personal hygiene during this trip. “How do you wash your clothes?” was the first question fired at me. I put down the photos from India and explained how I use the same bar of soap to wash myself, my hair and my clothes. I would use it to wash Bike and Trailer too, but they hadn’t started smelling yet, unlike myself, my hair and my clothes.

A volley of questions followed concerning camping logistics, regularity of showers, teeth cleaning habits and, finally, a thoughtful follow-up question from a small boy in the front. “How big is your bar of soap?” The image of a monstrous 90 x 40 x 15 centimetre bar of soap travelling solo in Trailer was a wonderful thought, but I told him the 125 grams of truth. I rode away from the school to waves from the students who seemed relieved to be ridding themselves of their dirty guest speaker.

I had just resolved to investigate some alternative hair-cleaning arrangements when the shoulder of the road suddenly narrowed, heralding the beginning of Macquarie Pass. As I rode higher and higher, mist set in and then some fine rain which I laughed at and imagined I was getting some sort of hydrating facial treatment in a fancy beauty salon (that probably has a wide range of specific soaps for different purposes). It had been blue skied and sunny just moments ago, and the line on my map hadn’t looked at all wet or slippery, so I was sure the rain would disappear soon.

Ten minutes later as I began my descent of the pass, I suddenly hoped I wouldn’t literally be laughing out of the other side of my face, in a terrible-disfiguring-accident way. The minimalist shoulder had become a non-existent one. Even with my brakes squeezed to their utmost, I hurtled though the hairpin bends with the engines of a constant stream of articulated trucks in my right ear. In contrast to this clamour, the echoes of birdcalls from the rainforest-filled ravine below rang in my left ear adding to the feeling of careering, slippery, almost air-borne terror.

I squinted through the rain, which was bucketing down, now more reminiscent of falling into a swimming pool than the gentle mist of a beauty treatment. Through the litres of water, I spotted a big red sign telling cars to travel at 15 km/h because of the steep declines for the next eight kilometres. I tried to imagine what sort of sign the road safety department would construct for Bike. Following the hypothetical instructions, I squeezed my brakes even harder. The brakes shrieked at me, and Bike slowed down but couldn’t quite stop. I clenched my teeth and executed a rolling dismount, thankfully finding myself on the road and not plummeting into the ravine. I walked the rest of the way, placing Bike and Trailer between the traffic and me. I exited the pass with my brakes and nerves completely worn through and mounted Bike once more, to ride with the heavy traffic headed into Wollongong.

The next morning I laid out my tools and spare parts and did my best to replace Bike’s brake pads. They had been ground down to the metal bases by Macquarie Pass, and it seemed the denuded pads had also worn into the rims of the wheels. On close inspection, I found there were no actual holes in the rims, so I decided to ignore the situation. I was feeling rather proud of my mechanical victory of fitting the new brakes and didn’t want any pesky wheel rim issues spoiling my mood.

I headed into Royal National Park and revelled in the absence of rain, trucks and red signs. I could look at the sparkling ocean views all I wanted without interruption. Until my gears went demented. Dropping into my lowest gear to climb a hill, cogs clicked, whirred, and refused to function. I gave Bike a lecture along the lines of “I spend my morning fixing your brakes, and this is how you thank me?” and got off to start fiddling. I pulled wires and twisted screws and managed to reduce my gear-changing capacity to half of Bike’s advertised 27 speeds. After an-other ten minutes with a spanner and having done further damage, I gave in before we became a single speed rig.

Gears became less of an issue when I hit a section of the road that was closed for road works. I faced a choice between a 40-kilometre detour or catching a train for two stops. I decided to railroad it, to the dismay of Bike and Trailer. They resisted every step of the way as I pushed them up a near-vertical hill to the train station, let them bump and shudder down a huge flight of stairs to get to the platform and folded them into a complex origami design to fit them into the annexe of the train.

The three of us limped into Sydney and tracked down some family friends who had a pile of mail and lunch waiting for me. Col took Bike aside and swiftly sorted out the brake and gear situation. I would normally have felt embarrassed by this, but given that Pam and Col are acquainted with a few generations of my family, they are aware of the DIY genes I have to work with. The fact that I had not burst a water main, electrocuted myself or found myself stuck naked inside a newly painted bathtub while wrecking my brakes is actually impressive for someone from my family.

After lunch, Col got on his own bike and led me along his favourite route into the city centre. I soon realised we must have very different tastes. The sensations of imminent death or injury I experienced on Macquarie Pass started flashing back to me as we dodged flocks of pedestrians, hijacked escalators and sneaked into bus lanes. I summoned the calming techniques I have been developing for stressful riding situations: breath holding, brow furrowing and jaw clenching got me through some manoeuvres while humming or singing worked for others. Whenever Col turned around to check I was still behind him, I made sure I had a smile and unfurrowed brow for show.

Reaching the end of my death-defying escorted tour, I farewelled Col and found some old high school friends who live in a tall block of apartments. With some quiet words of apology to Bike and Trailer, I hauled them up the fire stairs to the roof. There I left them to recover from the trauma of the last few days with a view of the Sydney Opera House and the Harbour Bridge.

I settled in a few levels down with Rebecca and Brett. Since one is a chiropractor and the other a journalist and reiki practitioner, these two were not only providing me with a bed, meals and company for a few days, but also alignments, interviews and some channelling of universal energy. Kindly, they didn’t mention my grubbiness or grimy fingernails, although a gift from Rebecca of Chanel Shimmering Décolletage Gel may have been a subtle hint not to let myself go too much.