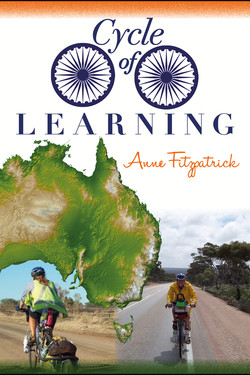

Читать книгу Cycle of Learning - Anne Fitzpatrick - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1: See You If You Get Back

ОглавлениеAdelaide – Murray Bridge – Tailem Bend – Meningie – Kingston – Southend – Mount Gambier – Dartmoor – Warrnambool – Colac – Geelong – Werribee – Melbourne

Totals: 1,148 kilometres – 63 hours 3 minutes – $1,139 raised

Wednesday 2 February 2005

Adelaide to Murray Bridge, South Australia

96 kilometres – 6 hours

As the digital display on my odometer clicked over to 45 km/h, I felt my bicycle trailer begin wobbling from left to right. The wobbles spread through the trailer, into the frame of the bike and then the handlebars. I tried to keep my centre of balance low as I battled to get control back. 48 km/h. Through the drizzle and the wet hair in my eyes, I took note of the sharp turn racing to meet me. 51 km/h. I flicked my eyes to the left to check how many inches I had between me and the embankment. 53 km/h. I willed my bike, still shaking and shuddering from side to side, closer to the edge to leave room for the car I heard approaching from behind.

Just as I was ducking under a rogue branch encroaching onto my limited part of the road, I had a vivid flash of recollection from a few weeks ago. I could clearly see the bright yellow sticker I’d peeled off the trailer, printed in an important-looking font: WARNING. DO NOT EXCEED 42 KM/H. I glanced down and saw my odometer click over to 56.

I gritted my teeth and tried to ease on the brakes, but let go as the wheels started skidding.

In the midst of my panic, one more useless memory resurrected itself: Susannah handing me a good-luck card as she left my send-off party. “See you next year. If you get back,” was her earnest farewell.

Dying on the first day of my bike ride would be so humiliating.

“So, she was riding her bike around Australia? How far had she travelled?” the investigating police would ask my parents.

“About 20 kilometres, Sergeant.”

“And was she adequately prepared, Mrs Fitzpatrick?”

“Well, she did do one practice ride last week. I had to pick her up though, after half an hour, when she got a puncture.”

The officer would add something to his notebook about possible genetic megalomania and incompetence, while the representative from the trailer company would pull my odometer from the wreckage. Through the cracked screen, the number 56 would still be visible. “It’s a bright yellow sticker. We use capitals AND italics. What more can we do?” the rep would mutter.

We survived though. All three of us – Bike, Trailer and I – made it to the bottom of the hill, shaken but intact. The rest of the day we stayed below the sacrosanct 42 km/h but I continued to have some leadership issues. Before starting my ride today, I had assumed that I would be the one in charge of this small, but – thanks to three metres of marine-quality tape – highly reflective crew. This was not proving to be the case. The entire ride to Murray Bridge was a series of wrestling bouts between the three of us. Generally, it was one on one, but at times, it turned into an all-in brawl with everyone wanting to go in conflicting directions and some of us sliding down embankments or lying down on the side of the road stubbornly refusing to get up.

Bike and Trailer do have the upper hand on me in that I’m not well informed when it comes to mechanical objects. Bike is a silver Shogun Metro-LX and people say he has good components. I generally respond with a nod and respectful look on my face to hide the fact I don’t know what “components” are. I have managed to attach bar-ends, a bell, rack and side mirror to him along with the reflective tape. The last thing I added was a kickstand. I was warned by bike-expert friends that this is not a hard-core accessory and will add unnecessary weight, but I love a bike that can stand up for itself. After commenting on Bike’s components, people turn to Trailer and ask if he is made of aluminium, which leads me to suspect that he is. He has a single wheel at the rear and a tall yellow flag, which I am hoping will prevent us from getting squashed by a truck.

Trundling into Murray Bridge at 7 pm tonight, I couldn’t be happier. A damp and wobbly 96 kilometres through the Adelaide hills was a welcome change from wading through administrative preparations for this solo, fundraising bike-ride around Australia. I’ve still got some logistical issues to deal with, namely, a lack of outdoor expertise, a daunting fundraising target, and a deep-set aversion to asking people for anything, but I’ve started. 96 kilometres down. 20,000 to go.

Saturday 5 February

Meningie to Kingston, South Australia

150 kilometres – 9 hours 3 minutes

Having an emu trot past me while gliding along a sunny, empty highway felt like a suitable birthday present today. While I’m feeling rather sore as I get used to the physical demands of my new lifestyle, the freedom of the open roads is wonderful compensation. Cycling provides just the right speed, lack of engine noise and wealth of sensory input to enjoy the landscape in a way that is unique to this mode of transport. Some of the sensory input, such as the smell of roadkill, requires extra commitment to appreciate but, overall, having the space and time to fully take in where I am has been enjoyable.

I’m not usually one to anthropomorphise, but today’s birthday emu seemed much friendlier than the two lycra-clad Danes who passed me yesterday. When I saw them in the distance behind me, just out of Tailem Bend, I stopped and waited, assuming that when cyclists meet each other on the road they share camaraderie and cycling tales with each other. And maybe there was some camaraderie in the indifferent glance the duo gave me as they sped past. I dejectedly watched the Danish flags on the backs of their shirts fade into the distance. It seems I have a bit to learn about social conventions among long-distance cyclists. Or maybe I just need to learn Danish.

While my confidence is still a little low in the bike-riding department, the school-visiting side of my project has had a solid start. I met with about 150 students at a high school in Murray Bridge yesterday. After looking at a map to find India and, more specifically, the region of Kodaikanal in Tamil Nadu, I told the stories of some children from that area.

Valli

When I first went to Kodaikanal in 2001, I met an 11 year-old girl called Valli who was staying in the primary school hostel run by PEAK. Like the other 100 or so children there, she stayed in the hostel during term time so she could go to school. The village that she was from had a school, which she could not attend because Valli is from the Dalit community. Valli’s family, for generations, has done jobs that other people in the village consider unclean, such as cleaning sewage, slaughtering animals or making things from leather. In the urban centres of India, discrimination against Dalits has subsided and is less of an issue, but in many rural areas, it persists. In Valli’s village, Dalits either can’t go to the village school, or if they do, may be ignored or treated badly.

Staying at the hostel during term time meant that Valli went to school regularly, had help with her homework, ate three healthy meals a day and learnt about social issues as well. A small group of Jesuit Fathers and Brothers oversee the hostel organisation, while local women, referred to as “Akkaa” (older sister), look after the day-to-day needs of the children. When parents bring and pick up their children at the beginning and end of term, they stay for programs discussing hygiene, nutrition, education and agricultural techniques, and hear from local Dalit and Adhivasi activists.

Being one of the oldest in her hostel, Valli often looked after the younger children and helped prepare meals. She was a clever girl, was doing well at school, and had a cheeky sense of humour.

When I returned to Kodaikanal in 2004, Valli wasn’t in the hostel anymore. I hoped she had moved on to the hostel in town for girls in high school, but it turned out that she had returned to her village soon after my last visit. She was working with her parents as a coolie (agricultural labourer), picking beans for a nearby landowner. Given she would have been 14 by then, there was a good chance that her parents had already arranged her marriage.

Eswaran

Another student I met on my first visit was a nine-year-old Adhivasi boy called Eswaran. He was the first person in his village to be studying at Year 5 level. When I returned in 2004, I met Eswaran again, this time at the senior boys hostel, and he greeted me with a handshake and a “Hello, sister”. Eswaran smiled proudly as the hostel warden informed me he was ranked first in his class at the local high school.

Eswaran, aged 12 years, 2004.

This is Eswaran’s story.

To reach the village I am from you must catch one bus down to the plains, catch another bus for a half-hour trip, and then climb on foot for three hours. It is very isolated and has no facilities. The government refuses to help the people of my village build houses, so we live in huts.

The government also refused to supply water to the village, so the villagers saved and put their money together to get a pipe that brings in water from a nearby stream. Otherwise, we would have to carry water a very long way. There is no hospital. If someone becomes sick, they have to walk for three hours to get help. There is also no school, although there is a village television.

I go back to my village four times a year, where I play cricket, go swimming and work as a coolie to help earn money for my family. There are eight people in my family; I have two older sisters, one older brother, one younger brother and one younger sister. My older siblings did not go to school, but my younger brother and sister do. My family do not live in the village proper, but on the property of the landlord of a nearby plantation, which we look after for him.

My family and the other people who work for this landlord get paid 50 rupees a day for men and 40 rupees for women. [At this time one Australian dollar was equivalent to 30 Indian rupees.] They have to travel a long way to a different village where the landlord lives, though, to collect their wages.

I enjoy studying, particularly English and Tamil. When I’m older, I would like to be a government official to help the people so that they don’t have to work so hard. I think study is good as it helps people get better jobs than doing difficult labour.

Students in the Murray Bridge audience put forward ideas of how education could benefit young people like Valli, Eswaran and themselves: reading and writing, job opportunities, managing money, problem solving, communicating and negotiating, the chance to help people and the skills to change communities.

We finished the talk with questions about Bike, Trailer and the ride, during which the students showed a morbid fascination with the hows, the wheres and the whys of my falling-off-Bike statistics. At least they didn’t hold my bike-riding ineptitude against me, unlike some Danes I could think of.

Monday 7 February

Southend to Mount Gambier, South Australia

84 kilometres – 4 hours 14 minutes

Today I began my media campaign.

Christine, the Adelaide coordinator of Cycle of Learning, and I had exchanged a flurry of phone calls as I made my way through the pine forests leading into Mount Gambier. “They want to meet you at the top of Hay Drive. You should see the signs just as you come into town.”

“OK. I wonder why there. Do you think that’s where the TV station is?”

“Who knows? It doesn’t matter as long as you’re getting some publicity. Remember to mention the website and that you’re tax deductible.”

Christine and I have been friends since the first day of primary school. Even at that stage she was outlandishly clever. Not just smart in that she knew about negative numbers and how to read and write before she started school, but clever in that she had an overflowing imagination, was braver than a five year old should probably be and, in my case anyway, was able to get other children to do whatever she wanted. This worked quite well since I was extremely timid when I was young, and needed someone to drag me along on their adventures with them. For a shy child like me, having an anarchic friend like Christine – who bit people to make a point, hit boys with chess boards when she had to, and organised secret societies that involved you breaking school rules and stealing things – was probably just what I needed to balance out my meekness.

Since primary school Christine has settled down in some ways – I haven’t seen her bite or hit anyone with a chessboard for ages now. What remains the same, though, is how excited she gets by ideas. Eighteen years ago, it was excitement about how we were going to booby trap a bedroom, or about an atlas we were making for an imaginary world. Today it’s excitement about any new undertaking that she or her friends are thinking of embarking on – travel, study, a new recipe. While Christine has been helping me organise Cycle of Learning, this excitement has been so valuable. Instead of falling into a pit of worrying about what I’ve taken on, Christine and her excitement has helped things feel positive and achievable and worth doing.

Adelaide Coordinator of Cycle of Learning is what we decided to call Christine’s role for this project, which she is balancing with dashing off a PhD. She is doing all the things in Adelaide that I can’t while I am on my bike and out of range of phones and computers.

For all her logistical support to me today, Christine forgot to remind me not to sweat on screen. By the time I inched my way up the hill, I was dripping with sweat and – checking in my handlebar mirror – an almost fluorescent shade of pink. It was not the image I had hoped to start my life in the media with. The interview began before I’d even got my helmet off, and was over in a few short minutes.

Perspiration issues aside, today on camera I came face to sweaty face with one of the biggest challenges of Cycle of Learning.

“So, what are you riding your bike around Australia for?”

“To raise money to help support disadvantaged young people in India through high school and tertiary education. And to raise awareness for Australian students about the role that education can play in overcoming social disadvantage … and to promote bike riding.”

It’s not exactly a cause that rolls off the tongue, or keeps the listener’s attention past the to help support … part. I feel quite envious of those cycling fundraisers that can answer with “for an orphanage”. Or “to stop animal cruelty”. Even something like “for world peace” would be more three-minute TV interview friendly.

As well as my dishevelled brush with local TV, I had two schools to visit in town, an invitation to speak at a Rotary club and – in a departure from the caravan parks I’ve been staying in – accommodation with two families for my time in town. One is the parents of Christine’s housemate and the other is a colleague of my mother’s. It was quite lovely to have the hospitality of these families that I had never met before but who were willing to offer their support through loose and stretched out connections.

Now that I was starting to line up speaking gigs, and had people hosting me on my journey, Cycle of Learning was finally being transformed into something real and tangible. In the months leading up to the ride it was at first just an idea-seed, then an abstract future event incubating while I put in hours behind computers, sent out information, looked at maps, got advice, made phone calls and shopped for camping gear I didn’t know how to use. Even once I mounted my bike and left Adelaide, I still felt like I was trying to conjure something out of nothing by claiming “I will ride around Australia and raise fifty thousand dollars”. After 500 kilometres or so, I no longer felt like I was pretending. I was over the first hurdle now that Cycle of Learning had a life – albeit, a very young one – of its own. I was just not entirely sure what it would grow into, and if it would match the ambitious plans spun for it.

Wednesday 16 February

Geelong to outer Melbourne, Victoria

84 kilometres – 3 hours 59 minutes

I rode the freeway from Geelong to Melbourne this afternoon for the second time in as many days. I had been staying in Geelong with my cousin Heidi and her husband Tim. As much as they have to love me because we’re family, I think I may have outstayed my welcome by a few days, half a dozen burritos and a garage break-in.

Heidi made a pre-emptive phone call prior to my arrival on Saturday to find out what I wanted for dinner. I rolled in to a Mexican extravaganza and warm welcomes from hosts I knew well enough to borrow clothes from so I could do a 99% wardrobe wash (I felt asking to borrow a pair of undies would be overstepping a certain line, even between cousins).

On Sunday, Heidi and Tim had some commitments in Melbourne so they left me alone in the house for a few hours with the leftovers from the previous night’s dinner. On their return they were polite enough not to mention the large gap in the fridge where those leftovers had been, or the salsa stain on their t-shirt I was still wearing.

I could sense a renewed confidence in me when they had to leave for work on Monday morning. They must have felt it was OK to leave me since there was no opened food that I could demolish and I was back in my own clothes. Also, they knew I would be kept out of mischief since I had a visit to a school nearby which would take up much of my day.

I watched some morning television until it was time to leave for the school. It was at this point I realised I had somehow misplaced the keys to Heidi and Tim’s house and shed where Bike and Trailer were safely locked away.

After a lot of general panicked rushing around followed by some inspired work on the louvred windows of the shed, I got us all to the school, but it was lucky that the police hadn’t driven by while I was breaking into the shed and bleeding all over its windows. At least the visit went well with the local primary school, where I visited each of the classes. We spoke some Tamil to each other (the language spoken in Kodaikanal) and thought of lots of reasons why bicycles are a great way of getting around – not least because it’s easier to drag a bike out of a shed window than a car.

Tim found another set of keys and gave them to me so I could lock up on the way out when I left for Melbourne the next day. In the morning, I waved Tim and Heidi farewell as they drove off to work and sat with the keys in my hand until my departure time. Proud of myself, I locked the doors, hid the keys in the nominated spot and headed for the highway. My plan was to stop at a school in Werribee before riding the rest of the highway into Melbourne by nightfall.

After the school visit and a photo shoot for the local newspaper, I pointed Bike north, ready to hit the bright lights of Melbourne. Luckily, I decided to check in with Christine in Adelaide first, and received instructions for a new assignment. I turned Bike 180 degrees and headed back to Geelong since the assignment involved speaking at a school there the next day.

After my unexpected return, I suspect Heidi and Tim were considering changing their locks (and if that failed, their address) to avoid the possibility of me continually turning up at their house unannounced. They may have had to change their locks anyway if they weren’t able to find those keys.