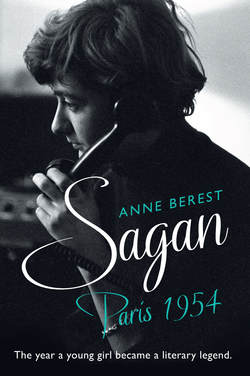

Читать книгу Sagan, Paris 1954 - Anne Berest - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

16 January

ОглавлениеBefore I recount what happened on the night of 16–17 January 1954, the night René Julliard read the manuscript of Bonjour Tristesse for the first time and wanted to publish it before he had even reached the last page, I must describe something that happened to me yesterday. It was such a strange thing that I wonder if I really did experience it, so strange that I could not say exactly what was going on.

I had decided to make an appointment with a clairvoyant, because, after I had written the episode with the fortune-teller, I reckoned that for me to meet a ‘real’ clairvoyant would be useful for the book and would make my description a bit less kitsch.

There are two sorts of writers. There are those who plumb their own depths to extract all the black gold they can find there and who, for that reason, are forced to live a life of asceticism. And there are those who need to experience things in order to write about them and who lose their way as they journey through life on the edge of a fantasy world, obliged to lead a kind of existence that sometimes proves fatal to them, as the wild ass’s skin does to the hero in Balzac’s story.

Be that as it may, I had made an appointment with the clairvoyant using the book as a pretext even though, probably, at an unconscious level, I wanted just as much to hear things about my personal life: my separation from the father of my daughter was looking as if it might be permanent and never in my life had I felt quite as lost as I did then. But instead of speaking to her about that, I put the following question: ‘I am writing a book at the moment. Can you see it?’ This is what I asked the clairvoyant when I met her in her studio near the Anvers Métro station, which in the fifties was the exact location – and I am not making this up – of the Pigalle carnival.

(What I am going to write next is the exact transcription of the notes I scribbled down in the course of our conversation. I am reproducing the words just as they were said to me, without any attempt to dress them up stylistically or to impose any kind of coherence on them after the event.

I know that most readers will not for one moment accept the veracity of what I am going to report. Yet it is all true and I leave it to each individual to interpret as they wish, and as best they can, the remarkable occurrence that I was party to and that I restrict myself here to conveying as faithfully as possible.)

‘Yes, I can see that you are writing a book on someone’s life. It’s the life of a woman who lived as a man would. She was very masculine. But she was benevolent towards people. She was a woman who had experienced everything. She did whatever she wanted to do. But she did it alone. She experienced everything on her own.

‘She was a woman who felt misunderstood. She had stepped aside from time. For her there was no longer any such thing as a calendar, only a life lived in the present moment.