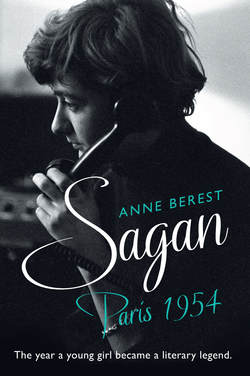

Читать книгу Sagan, Paris 1954 - Anne Berest - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6 January

ОглавлениеThis is a book I have to write quickly, and it is taking shape and gradually coming into focus.

It is to be neither a biography, nor a journal, nor a novel. Let’s just call it a story.

The idea is that it’s the story of a girl, a very young girl, writing her first novel.

I will be cataloguing the various stages in the life of a budding author: her excitement, her fearfulness, her sense of anticipation.

My book will be about the progress of another book, from the moment the manuscript is sent off to the point at which it receives a literary prize. My plan is to focus on a few days in one year, the year in which the heroine’s life will be turned upside down. With every passing day and week, the anonymous teenager will be on her way to becoming a recognised writer.

If this were a made-up story, I would have to work on the issue of plausibility in order to get the reader to accept that certain incredible things can actually happen. I mean things like a book becoming a huge success while simultaneously causing a monumental scandal; I mean things like a girl who had not yet come of age becoming a social phenomenon and the most famous Frenchwoman of her era.

But that story is true. So my task is to understand and then explain to others how implausible things can suddenly happen in life. I have to be able to show how a book can explode on the scene like a bomb, how it can burst forth like springtime, how it can have an impact like the catastrophe in a Greek tragedy.

‘Françoise,’ says Jacques, ‘are you sure you won’t be sad if your novel isn’t published?’

‘I don’t know. We’ll see. I like writing.’

‘Why do you like writing?’ asks Jacques. He can see that his sister does not envisage being met with rejection, still less with indifference.

‘To write a novel is to construct a lie. I like telling lies. I have always lied,’ she answers laughingly. ‘Come on, wish me luck.’8

I visualise this girl in the Métro, sitting among other girls. They are all dressed just like their mothers, in long coats down to their ankles, Jacques Fath-style coats in dyed wool, or tweed coats. They wear little silk scarves and have their hair tied back, revealing the few pearls round their necks – there are no pierced ears. They are all dressed severely. It is an era when the transition from childhood to adulthood is a brutal one and there is nothing in between.

Like the others, Françoise is wearing a heavy coat and a red-and-white striped blouse buttoned all the way up. She could be anything from fifteen to thirty.

This is the last stage in her life when Françoise’s face is not the face of celebrity. These are the last weeks in the whole of her existence when she is still a girl like other girls, a girl of eighteen. She doesn’t know that there’s not much of the old life left for her, nor that everything is about to be turned upside down because of what she is carrying, like a cancer, under her arm. Those sheets of paper covered in words, typed up by a friend ‘because it’s neater like that’,9 are going to change her life for good. But we’re not there yet. For the moment, I see her observing people in the reflection of the carriage windows. She feels sorry for a girl who has no ankles and whose calves go straight up and down like broomsticks. It’s unfair that some people are not beautiful, she thinks, as she is lulled by the sound of the train.

Whenever I came across people who weren’t physically attractive, I experienced a sort of uneasiness, a sense of lack; the fact that they were resigned to being unattractive struck me as being an unseemly failing on their part. For, after all, what was our aim in life, if not to be pleasing to others?10

Françoise had got on at Wagram and had changed at Saint-Lazare, finally to emerge at the exit in Rue du Bac, where the wind blew up under her coat. Turning right into Rue de l’Université, she walks along to number 30, the premises of the publisher Julliard. Her hand is frozen when she pushes open the massive green door, tottering as she does so. She turns round. There is a young man behind her. They barely exchange glances but both guess that they are there for the same reason.

So they approach the desk together and naturally the receptionist addresses the young man.

‘Are you here to submit a manuscript?’

‘Yes,’ he replies timidly.

‘Don’t bother phoning for a reply. You’ll get a letter in a few weeks. If your manuscript is rejected, you can come back here and pick it up.’

‘But I don’t live near Paris,’ he replies.

‘In that case, come back with some stamped addressed envelopes. Thank you, and good day to you, Monsieur. Good day, Mademoiselle.’

The young man hurries out in search of a post office and some stamps. Françoise waits politely; she waits patiently and graciously, still facing the woman, who has buried her nose in her work again. ‘So sorry, I thought you were with the boy!’ exclaims the receptionist when at length she realises her mistake.

‘It really doesn’t matter,’ replies Françoise. ‘It really doesn’t matter at all. Please don’t apologise.’

Now we see Françoise (somewhat lighter, having been relieved of one manuscript) trotting off in the direction of the Librairie Gallimard, the high temple of publishing. This august establishment is only a short walk from Julliard, at number 5 Rue Sébastien-Bottin – the street is called after the man who gave his name to a directory of commerce and industry.

There is no one at reception. She hesitates. Her friend Florence works there but only started a few days ago. It would seem too casual just to wander off down the corridors looking for her.

So Françoise waits, politely, patiently and graciously. A young woman, hurrying past, asks her if she is there to drop off a manuscript. Françoise nods. The young woman reaches forward automatically to take the yellow folder and then declares in a single breath, ‘Don’t bother phoning for a reply you’ll get a letter in a few weeks and if your manuscript is rejected you can come back here and pick it up.’

Françoise’s next port of call is Éditions Plon, based in Rue Garancière, a quiet little street that doesn’t get too much sun, a pleasant street, its name evoking that of a flower.

I can hear Françoise’s footsteps. She is slightly out of breath, wondering, like someone wagering on several numbers in roulette, which number will come up. Which publishing firm will turn her destiny upside down? I see her frail little form, head down, lost in thought when her path crosses that of two men preoccupied by weighty matters.

The two men are of equal height.

The first man is all forehead: it is wide and pale and underneath it is a birdlike face. His beard and large spectacles seem almost to have been stuck on, the features beneath them being so chiselled. He is assistant director at the Musée de l’Homme and, apart from his thesis, he has still only published a single work, with Presses Universitaires de France. Yet, at forty-six, he is no youngster. The second man, the one whose hands dart hither and thither in the air like insects, has his heart set on bringing out Tristes Tropiques. This fledgling publisher, much younger than Claude Lévi-Strauss, has black, unruly locks and a generous mouth. Strikingly handsome, he is the first man to have reached the geomagnetic North Pole. Jean Malaurie is launching a new series for Plon, entitled Terre Humaine. He wants it to be the home for a new type of intellectual: author-explorers, men defined solely by the terrain they have covered. It is this editorial dream that the explorer of Greenland is explaining as he walks along Rue Garancière, with the Senate behind him, while young Françoise passes them coming from the opposite direction, her ankle boots click-clacking on the cobbles.

Françoise goes into an imposing mansion, the Hôtel de Sourdéac, which houses a printing works whose presses are always running at full tilt. But there is also on the premises a publishing firm, one that has made itself particularly receptive to literature and essays, called La Librairie Plon, les petits-fils de Plon & Nourrit.

On entering the courtyard, Françoise is overpowered by the smell of fresh ink, which then catches her by the throat as it mingles with the scent worn by the young woman at reception. Jolie Madame, the latest perfume from Pierre Balmain, is a mixture of violets and leather and has been popular as a gift this last Christmas. Jolie Madame goes through the same rigmarole as her predecessors: Are you submitting a manuscript? You can expect a letter. You’ll hear nothing for several weeks, etc.

The die is cast. With her arms now free and swinging by her side, Françoise crosses Place Saint-Sulpice in the cold of that sixth of January. All she is thinking of is dinner that evening, when her big sister Suzanne will be celebrating her thirtieth birthday.

As happens every year, her mother will have bought a huge galette des rois, still warm. And as happens every year, everyone will make sure that Kiki finds the charm hidden in it and gets to wear the crown.

To Françoise, thirty seems a lifetime, too far off to contemplate. She doesn’t know that, by the age of thirty, she will have been married and divorced twice, will be a mother, and a writer acclaimed throughout the world, her work adapted for the cinema by Otto Preminger, acted by Jean Seberg and sung by Juliette Gréco; she will be both loved and loathed and, in a terrible accident, she will have come close to death, a place beyond the reach of memory.

Between now and the age of thirty she has so much to experience.

Suddenly I visualise Françoise in the radiance of youth. I am more than thirty now and I feel out of place as – on the run from my own life – I immerse myself in the life of another. I am following in the tracks of a child; I see her cross the square by the side of the church of Saint-Sulpice. She crosses it diagonally, passing close to the fountain and its lions.

Fully preoccupied as she is by the thought of the birthday present she is planning to give her sister, Françoise does not know that she is being watched from behind the façade of the church by the painting by Delacroix.

It is of Jacob wrestling with the Angel.

His raised knee is a sign of his will. His muscular back tells of his resoluteness. And his arm and shoulder bespeak his determination to fight. Every sinew in the magnificent body of the man called Jacob is straining towards victory and, at daybreak, he will gain God’s favour because he, a natural man, has wrestled with the supernatural. But his thigh will be for ever marked by the injury he has sustained.

In every combat undertaken, in every task completed, in every victory gained, one must accept that something will be lost.

In every task completed.

In every combat undertaken.

One must accept that something will be lost.

What shall I lose through this book?