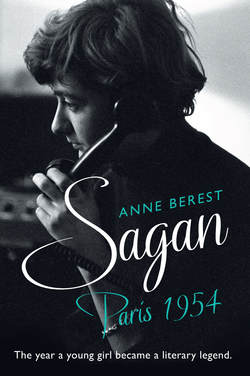

Читать книгу Sagan, Paris 1954 - Anne Berest - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4 January

ОглавлениеFor the second scene in this book, I would like to describe Françoise waking up in her childhood bedroom at her parents’ home in the elegant Monceau Plain district, at 167 Boulevard Malesherbes.

There, in a vast apartment from the Haussmann era, Pierre and Marie Quoirez, originally from the provinces, have installed their three children. As members of the bourgeoisie, they ‘both loved partying and had a liking for Bugattis. They drove round the roads at breakneck speed. My parents were youthful and up-to-the-minute.’4

Marie, the mother, is perfect. She is like a brown butterfly with blue wings and always impeccably turned out. She loves to laugh, loves going out, loves to make the most of everything the capital has to offer. Much later, Françoise will say of her that she did not live in the real world, that she was always somewhere else as she rummaged among her hats. But, for the moment, Françoise does not pay much attention to her mother. She has eyes only for her father, her ideal – Pierre. It was for him and by his side that she wrote her manuscript the previous summer, in just six weeks.

Françoise, of course, went to bed late the night before. She had been living it up with her brother Jacques. They had drunk whisky because, with whisky, you sink into a respectable melancholy that does not involve self-loathing – but, even so, this morning her eyelids seem full of grit.

Since daybreak, several people have gone into Françoise’s room. The first had been Julia Lafon, the girl from the plains of Cajarc, the limestone plateaux in the Lot. She is the family’s housekeeper and she comes in to gather up some blouses from Weill’s ready-to-wear collection. Next comes Marie Quoirez to encourage her younger daughter to get up at a suitable hour for a young lady of her age. But, oh well … she’s got the rest of her life to get up early.

Pierre, who is an engineer and the technical director of a factory, merely opens the door to look at his big girl sleeping. He remembers stroking her head when she sat on his lap in the Jaguar as a tiny child, her little hands on the wheel.

A yellow pillow lies on the ground, like a block of fresh butter. It’s the biggest pillow in the house and Françoise makes sure she has it so that she can read late into the night, comfortably propped up against the wall. The bedside table has a glass top, strewn with magazines and piles of books.

At the foot of the bed, on a fringed rug, an enormous record player is positioned at just the right distance so that Françoise only has to stretch out her arm, without getting out of bed, to turn her records over. On it I picture the Billie Holiday sleeve where you see that wonderful face, with a large flower behind the ear and pearls round her neck, just like Frida Kahlo.

The teenage girl, asleep on this morning of 4 January 1954, whose parents still call her by the pet name of ‘Kiki’, is far from imagining that in the not too distant future Lady Day will sing for her, in her presence, and will hug her and talk to her as a friend.

In order to put the finishing touches to this tableau – this imaginary representation of Françoise waking up – I have to decide what books will be lying on the bedside table.

Because this is the room of a girl who has set her sights on becoming a writer, I choose A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf.

I search for the book on my shelves in order to reread certain passages that I would like to quote here.

I study Woolf’s words, wondering what Françoise Sagan would have made of them. It’s like rediscovering a book you have just given as a present: putting yourself in your loved one’s shoes, you wonder what their feelings will be when they read it.

Yes, it’s clear that Françoise Sagan loved this book. I have to select two or three sentences from it, although I would like to include them all.

‘Why did men drink wine and women water?’

‘Of the two – the vote and the money – the money, I own, seemed infinitely the more important.’

‘Intellectual freedom depends upon material things’ or, again, ‘A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.’5

The pages of A Room of One’s Own bring a lump to my throat because I am reminded that when last I read the book I had dreams of becoming a writer and I wondered if one day I would have the necessary strength and courage.

Then my eyes light upon the very first page:

A Room of One’s Own

Virginia Woolf

Translated by Clara Malraux

Reading these words, I feel the veins in my neck throb, just as they do when you find something by chance that you hadn’t been looking for: a hidden love letter not intended for you; a 500-euro note just when you are short of money; or the offer of a trip when you want to get away from someone.

Clara had translated Virginia Woolf. That is, Clara Malraux, the mother of Sagan’s best friend.

So I was fully justified, justified at least in placing that book on Françoise’s bedside table. And why not even a copy with a dedication from the translator? ‘To Françoise, who will one day be a writer.’ For that is what her daughter had told her a few weeks previously, having just read her friend’s manuscript at a single sitting: ‘Françoise is a writer.’

Now that I have set the scene, with the books, the music and the blouses, I can wake Françoise up. I can get her to rub her eyes like a child, as she does in a photograph taken in Saint-Tropez in which she is wearing a checked nightdress. Then, in the corridors of her parents’ apartment, she goes in search of her brother, who is her best friend as far as boys are concerned. Jacques Quoirez is twenty-seven. He has gone off to London to ‘get experience’ in a business there but he comes back to Paris for the end-of-year festivities. I am struck by the photographs of him that I have found in trawling through archives on the internet. He looks nothing like Françoise – you wouldn’t think they came from the same family.

Jacques has read his little sister’s manuscript.

Jacques has been impressed by what he has read.

Yet he is not a man to set aside his usual cynical attitude. With his stripy blazers, his threadbare Charvet shirts and his hide moccasins, he is the darling of the circles he moves in. He is blithe and devil-may-care and he possesses what is known as charm, which, in a man of leisure, is a terrible defect.

Not wishing either to flatter her or to fill her with false hope, Jacques has told her that the book she has written is a nice little composition,6 not at all bad for a first novel. He agrees to help his little sister parcel up the manuscripts, while at the same time giving her a warning: you have to be patient, and very patient at that, if you want to get yourself published. He has friends, some decidedly more gifted than she is and others with better contacts in the publishing world, who are still waiting for replies. Françoise, he muses, will soon discover that life isn’t as cushy everywhere as it is in Boulevard Malesherbes. Little Kiki has been so spoilt and pampered by their parents, Pierre and Marie, that one day she is going to have to be surprised by the real world. But the later the better, he thinks, for at the end of the day he loves his kid sister more than he loves any other woman.

All the same, Jacques has been impressed by ‘Franquette’. No one really believed that she would write that mysterious book of hers so quickly. In places he has recognised literary influences: the ‘warm, pink’ shell like the ham in Rimbaud’s ‘At the Green Inn’; the words of Cécile, with their echoes of Musset’s character Perdican; the quotations from Oscar Wilde and the influence of Choderlos de Laclos. But he has no wish to discourage her; there is nothing more tiresome than critics. We shall see – after all, this is a child who has always got what she wanted, from no matter who.

After much debate, they settle on three publishers, Gallimard, Plon and Julliard. They put the typed manuscripts in big yellow folders and Françoise asks her brother if he will write her address on them. She feels sure that confident masculine handwriting will put the publishers’ readers in a positive frame of mind.

Françoise Quoirez,

167 Boulevard Malesherbes.

When he has written the addresses, Jacques has a thought.

Françoise really must put her date of birth on the manuscripts. His hope is that the idea of a little eighteen-year-old will touch the hearts of the readers and that when they return the manuscripts they will perhaps be less nasty in their accompanying letters.

‘What if we added the phone number too?’ suggests Françoise.

‘What for?’ asks Jacques.

‘In case they want to take me on immediately! In case they really, really like the book!’

‘No, Françoise, no. That would look silly. Publishers don’t phone you. They send a letter.’

But Françoise is insistent. She agrees to include her date of birth as long as they add the phone number. So, on all three copies, Jacques writes:

Françoise Quoirez,

167 Boulevard Malesherbes.

Carnot 59-61. Date of birth: 21 June 1935.

He suddenly feels very afraid for his little sister.

‘Whatever happens, if this one doesn’t get published, you will write another, won’t you?’

‘Yes, of course. It won’t be the end of the world.’

‘Not even a little bit, OK?’

‘I don’t write in order to get published, you know. I write because, first and foremost, it’s something I enjoy doing.’

‘That’s just as well.’7

Smiling, and as a parting shot before closing the door behind her, Françoise calls out to her brother, ‘But I shall get published!’

At that very moment, on that fourth of January 1954, a boy of the same age – eighteen, to be precise – is recording two songs. It costs him four dollars, which he pays for out of his own pocket, and he records them in a small studio specialising in the black soul music of Memphis.

The songs are ‘My Happiness’ and ‘That’s When Your Heartaches Begin’.

Both those kids, Françoise Sagan and Elvis Presley, are going to need shoulders broad enough to bear the weight of what they are going to become in a few months’ time: two idols pursued by frenzied crowds. But today they have quite simply done something, and it all stems from there. You never lose out by just doing something; there is a chance you might even win. You have to take on board the risk of winning, and the young do not realise just what the consequences of winning can be.