Читать книгу Sagan, Paris 1954 - Anne Berest - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 January 1954

ОглавлениеI see a man of sixty-five leaving the New Year’s Eve party that has been organised in his honour, like someone walking out of their bedroom leaving the bed unmade. In any case, wherever he is going, the party’s over. Once, he made the heart of Paris beat faster, but today there is no one left for him to dance with: those he can truly converse with are dead – or have not yet been born.

I imagine a car in Rue de Montpensier dropping him off in the half-light of a day that is still hovering between the old year and the new. A young couple are just passing the impressive entrance to his home, whispering to each other.

The man watches the two figures as they scuttle through the cold of that early morning. He notices the way they pull each other along by the arm, like two crabs heading in the direction of the Seine. The young boy is not bad-looking, with his Joan of Arc haircut – like a page boy who has been lifted straight out of an illuminated manuscript.

It seems to me that these two characters, shining through the dawn, pass Cocteau without recognising him. I can hear the two teenagers break into ripples of laughter as they run off towards the Palais-Royal.

If you look more closely and if you listen to their high-pitched peals of mirth, you realise that they are both girls. One is called Françoise and the other Florence. Whenever they race each other through the streets of Paris, neither one wins. In the end Françoise always holds out her hand to Florence and draws her along at her own swift pace.

*

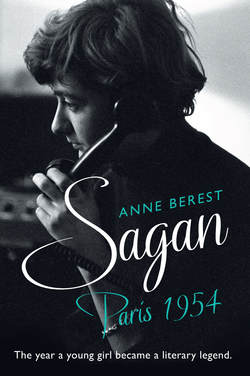

Over the coming months I am going to be writing a book about Françoise Sagan and it is with that scene, featuring Cocteau and the daybreak, that I would like to begin it.

My book is to be a journal of the year 1954, telling the story of the few months leading up to publication of Bonjour Tristesse.

A few months is not a very long time.

But I am going through one of the most painful periods of my life. Since the summer, I have been separated from the father of my daughter. I am weighed down by misery and I feel like a suitcase without a handle.

I am going to put an end to my grief through work. Night and day I am going to think about Sagan; day and night she will be my companion.

This will give me the best excuse for not seeing anyone: I have to read all the biographies, all the novels and all the interviews. Sagan gives me the courage to do this; she is the best possible source of comfort.

In my notebook with its brown paper cover I jot down phrases that I’ve gleaned here and there. I collect them, as I would the wise counsels of an older friend, a woman who has seen it all and who knows, therefore, that there is no advice to be given, that experience cannot be passed on and that the only thing we are able to bequeath to others is the testimony of our own existence, that is to say, the mere fact of it, which is the proof that people can come through every sort of situation and that happiness can sometimes return.

I make myself at home with her, just as I make myself at home in the various flats that people lend me these days. I borrow my friend Catherine’s shoes. I spray myself with Esther’s perfume, in her bathroom. I slip into the mindset of Françoise Sagan as if I were slipping on a pair of silk stockings – I inhabit her life in order to forget my own.

Here she is again with her friend Florence Malraux on the Pont des Arts, just as the new year makes its appearance in the sky above Paris between the Institut de France and the Eiffel Tower.

Ahead of them, the grimy façades of the Parisian buildings look like a huge accordion spilling out along the banks of the Seine. A sense of peace reigns, a thin film of frost covers the preceding years, like those white dust sheets that you throw over the furniture in country houses before you leave.

Thus each new year Paris draws away from the Occupation, transforming events into memories. And in the end, memories are always forgotten.

Florence and Françoise are children of wartime; in other words, strange creatures who began life at the end: they know the real God is Chance. And they know everything can go wrong. With that as your starting point, you’ve got to make the best of what you have.

They had been in the same class in the Cours Hattemer, a lycée in Rue de Londres, in the district round the Gare Saint-Lazare. It was a private school for children who were ‘special cases’.

Owing to a long illness, Florence had had to give up normal state school for a while.

As for Françoise, she had been expelled from every conceivable type of establishment, first from a convent school (le Couvent des Oiseaux) for her ‘failure to be deeply spiritual’, then from the Louise-de-Bettignies School for having ‘hanged a bust of Molière with a piece of string’1 – though would Molière not have appreciated being hanged in the form of this dreary, scholastic representation?

It was during this period that, as a little girl on her way to morning mass, she would pass the revellers in their dinner jackets, clutching champagne bottles, issuing from the nightclubs on Rue de Ponthieu.2 She was a child who believed adults had much more fun than children.

(I discover that a convent called ‘the Convent of the Birds’ really did exist. I used to believe that it was something made up by my mother who, when I was small, used to say about any little girl whom she thought rather silly, ‘She comes from the Convent of the Little Birds.’)

Françoise had been expelled from several religious establishments, but she did have to pass her baccalauréat. Fortunately, in 1885, a Mademoiselle Rose Hattemer had invented a method of learning that stimulated the intelligence rather than the memory. It was thanks to Rose that the two teenage girls met in the little playground of the experimental school.

Françoise was impressed by Florence, for Florence had been in the Resistance with her mother. And Florence was Jewish. (Yet France was not too keen on Jews after the war – they brought back bad memories.)

Florence was fascinated by Françoise because she asked questions that nobody asked. And because her mind worked in unexpected ways. And because she was never mawkish, as girls can be.

The two teenagers were going to become the very best of friends.

They shared a love of literature and they both subscribed to the same principle, namely, that you should treat great matters as if they were of little account and small matters as if they were great ones.

It was something that Françoise had come to understand as a result of the carefree life she had led and that Florence had come to understand as a result of her sombre life.

What they didn’t know was that they were going to spend the next fifty years of their lives hand in hand and that it was all going to go by in a flash.

Françoise had read Proust, and Florence, Dostoyevsky.3 Between them they had the century wrapped up and they swopped books as others swopped taffeta frocks.

But on that first of January 1954, as day breaks over the Pont des Arts, they still barely know each other.

‘We must make a vow,’ says Françoise.

‘Fine,’ replies Florence.

And the vow the two girls make is one and the same: they vow that Françoise will find a publisher.

Meanwhile, in Rue de Montpensier, Cocteau, who is ill, falls asleep, as he does every night, thinking of the young man he has loved so much. He is thinking of Radiguet. He thinks of him every second of every hour. Radiguet goes on living in him. And goes on dying too.