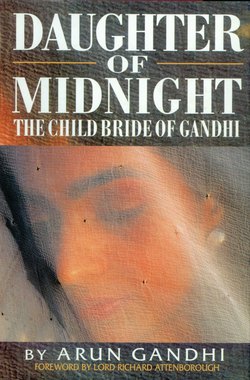

Читать книгу Daughter Of Midnight - The Child Bride of Gandhi - Arun Gandhi - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеIt promised to be the biggest wedding in Porbandar — or at least the most festive one anybody could remember.

Karamchand Gandhi had proposed the plan in a letter written some time in the summer of 1882, to his only surviving brother, Tulsidas, now the head of the Gandhi household in Porbandar. The time had come, Karamchand decided — the long-awaited marriages of Mohandas, 13, and Karsandas, his brother, 16, were to take place that autumn. What Karamchand had in mind, however, was a triple marriage ceremony.

His brother Tulsidas’ 17-year-old son Motilal was the only other unwed young man in the entire Gandhi family, and Karamchand, in his letter to Tulsidas asked, “Why not have a triple wedding?”

Some Gandhi biographers have suggested that Karamchand proposed having a triple wedding to save money. This may be so, but any savings would have been mainly for the benefit of the brides’ parents. Weddings can be ruinously expensive. By tradition most of the costs were borne by the bride’s family. But decisions as to how many wedding guests to invite, what kind of food to serve, what entertainment to provide, were not left to the discretion of the families involved. The community council of their caste or subcaste decided these matters — in this case, the Modh Vania caste committee in Porbandar — which set minimum standards based on the position, wealth, and prestige of the bridal couple’s parents. No excuses. Families wishing to protect their social, financial and religious position had to celebrate a wedding in a suitable and expected manner. They often went deeply into debt to do so.

The idea of letting three bridal families share the burden of these huge outlays of cash must have been vastly appealing to a man like Karamchand, as noted for his thoughtfulness as for his common sense.

But there were other considerations as well. Karamchand was now past 60, an advanced age for Indians at that time, and travel was becoming difficult for him. In those days before railroads came to the Kathiawar peninsula, it took five days by ox-cart to cover the 125 miles between Rajkot and Porbandar.

His brother Tulsidas was only two years younger, and both men wanted all the young Gandhis in their charge to be married while they could still take their rightful places in the ceremonies and celebrations. Besides, at such a big wedding they themselves could no doubt have the last huge celebration of their lives.

Karamchand did not disclose the wedding plans to his sons until all arrangements had been made. Sixteen-year-old Karsandas took an immediate interest in the prospect, wondering aloud what his bride-to-be, a girl named Ganga, would be like. But young Mohandas reacted with indifference. A first-year student at the local Rajkot high school now, he was still shy and self-absorbed. Though vaguely aware that he was betrothed he had given little thought to marriage, and, unlike Kastur, he had received no instruction about the subject whatsoever. But once Mohandas grew accustomed to the idea — to a 13-year-old, getting married meant acquiring a new friend, a sort of permanent playmate — he too became intrigued. Karamchand arranged for the boys to miss school, and the whole family made plans to travel to Porbandar together for several days of wedding festivities.

For Kastur and the other prospective brides in Porbandar — Ganga, who was to marry Karsandas, and Harkunwar, betrothed to Motilal Gandhi — the activities had begun months earlier. Though no one had told Kastur what all the secret messages and whispered conversations were about, she sensed that something momentous was taking place.

Weddings usually took place at the bride’s home, but this time since three couples were to be wed, a hall had to be hired. Menus for the wedding feast had to be drawn up, decorations, flowers, cooking utensils and serving pieces acquired. Extra servants would be needed; drummers, flautists, singers must be engaged. Carriages must be rented and mares for the bridegrooms to ride had to be found. Trousseaus had to be bought, new clothes for the families must be made, and a hundred other things attended to.

Before inviting a single guest Gokaldas Kapadia wrote out an invitation in red ink and, with his wife Vrajkunwerba, went to the temple and laid it at the feet of their family god. Only after the Lord was invited were friends and relatives given their invitations. In ancient India invitations had to be personally delivered, not mailed.

Kastur was excited. It was the event for which she had been preparing for so long. But now that the time had come, it was confusing and overwhelming. She was happy but keenly aware that she would soon be leaving her parents, her brothers, the familiar surroundings of Porbandar and her childhood behind. For a 13-year-old girl, it was more than a bit scary.

Such doubts were fleeting — her confidence in the future was strong. In her room in Porbandar, ready for the long trip to Rajkot, was her ornate cedar wood chest filled with new clothes. Another carved teakwood box held her wedding jewellery: gold bracelets, necklaces, bangles; gold rings and studs for her ears and her nose.

In Rajkot, as the wedding date approached, plans had changed. Karamchand Gandhi was delayed by urgent official duties. The Thakore of Rajkot, the local prince whom he served as prime minister, considered him indispensable. To make sure the rest of the family arrived in time for the festivities, Karamchand sent them off on the five-day ox-cart journey; he would follow soon. The prince had offered Karamchand the use of his own fast horses, the royal buggy, and an experienced driver. Karamchand promised Putliba and his sons he would be there for the ceremony on time.

For the entire week preceding the wedding the Kapadia house was filled with relatives, friends, neighbours, helping cook sumptuous delicacies for the wedding feast. As they worked they sang wedding songs for Kastur. Some were humorous to tease or amuse the bride and help relieve her nervousness; others were instructive to convey advice and information for newlyweds.

The day before the wedding, Kastur was given a special beauty treatment with pithi, a fragrant mixture of turmeric, almond and sandalwood mixed in fresh cream. This was a ritual performed for all prospective Hindu brides. Kastur’s mother, aunts, female cousins and friends took turns daubing this ointment on her young body. A similar ritual was performed for each of the young bridegrooms by their male relatives.

On the day of the wedding, Kastur’s married female friends and relatives gave her a ceremonial bath with water made fragrant by herbs and perfumes. She was groomed and then, using a paste made from henna leaves, the women painted intricate designs on Kastur’s hands and feet. She was then ready to be dressed in her beautiful new sari.

Smiling now, Vrajkunwerba touched her daughter’s forehead lightly with her finger, placing there a dot of red powder on wax, the familiar vermillion kumkum mark, a sign of being blessed. Finally, the traditional red sari, a cobweb of filmy silk, was arranged over her head and shoulders as the wedding veil. Kastur was ready.

But mixed with joy there was consternation at the Gandhi home. Karamchand had not yet arrived from Rajkot. It would be sad if the children he loved had to be married without him. Postponement was unthinkable; the exact moment of the wedding is chosen with great care. To ensure the union takes place at a propitious moment a blade of grass is placed between their palms, to be withdrawn at the exact instant when the position of the stars and planets is right.

At last Karamchand’s buggy arrived, much to the relief of the family. But Karamchand was bandaged and bruised and limping, and had much to explain.

To arrive on time the horses sped over the rough, dirt roads, he said, and the light buggy bounced and bumped so that every bone in his body was shaken. Early this morning, fearing he was going to miss the weddings, he began egging the driver on.

“Can’t you get the horses to move faster?” Karamchand groused.

“We’re going as fast as we can, sir,” the poor man would reply.

Then it happened. The right wheels of the buggy hit a loose boulder on the road. The buggy tilted crazily to the left and then overturned. Karamchand and the driver were both badly shaken. Then he realized that he also had cuts and bruises all over his body.

With the help of some farmers, they set the buggy on its wheels. It seemed to be intact. While they rested the horses, Karamchand tore up a white dhoti, or loincloth and used it to bandage his wounds. They had resumed the journey and somehow got to Porbandar — in time. The ceremonies, Karamchand announced triumphantly, could take place exactly as planned.

He brushed aside the concern of the family; he maintained he was not seriously hurt As soon as he cleaned up, he would be as good as new.

The three brides, hidden inside curtained carriages, their faces veiled, were brought by their parents to the wedding hall. Inside, three canopies had been set up where the actual ceremonies would take place. Decorative poles, festooned with flowers, marked the four corners of each canopy, and at each corner were piled brass pots in the form of a pyramid. The brides waited.

Meanwhile, a stately procession led by a band of musicians was making its way through the lanes of Porbandar. The grooms, in all their finery, mounted the rented mares (also decorated and garlanded with flowers) and began their journey to the hall. On foot were their mothers and other female relatives, singing special wedding songs. Then came everyone else — relatives, friends, wedding guests, even some curious bystanders. This time, all agreed — it was the biggest wedding celebration Porbandar had ever seen.

Mohandas was brought to the decorated booth and seated on a low wooden stool facing east. Only after Mohandas had been seated was Kastur brought to the booth by her maternal uncle and seated on another stool, which faced to the west. Through her veil, she got only a peek at the boy who was waiting for her. Almost immediately, a white curtain was drawn between them. She was glad to see her parents, Gokaldas and Vrajkunwerba, seated next to her facing to the north.

For many minutes, Kastur sat listening as the priest recited the marriage vows in Sanskrit. At last, her father Gokaldas rose and holding several blades of grass in his hand announced the cycle, the age, the year, the season, the position of the planets, the day, the continent, the country, the province, the town, and the place where the ceremony was being held. After these precise directions were conveyed to a listening god, Gokaldas declared that he was handing over his healthy daughter Kastur to the bridegroom Mohandas, and he relinquished all claims on her. He then took Kastur’s hand and placed it in Mohandas’ right hand with a blade of grass separating the two palms.

But the ceremony was not over. The newlyweds were then seated next to each other while the priest said a few more verses, and then it was time to perform the final ritual, the Saptapadi, or Seven Steps. Mohan and Kastur stood up, side by side, looking very serious.

Together, they took the first of seven steps as husband and wife, repeating with each step the verses they had memorised. Seven small heaps of rice had been arranged to mark the steps, and Kastur had been instructed to trample one heap of rice with the big toe of her right foot, with each step forward (the significance of trampling the rice-heaps is not known). Here is what they said that day, Mohandas speaking first, Kastur responding.

Take one step, that we may have strength of will.

In every worthy wish of yours, I shall be your helpmate.

Take the second step, that we may be filled with vigour.

In every worthy wish of yours, I shall be your helpmate.

Take the third step, that we may live in ever-increasing prosperity.

Your joys and sorrows I will share.

Take the fourth step, that we may be ever full of joy.

I will ever live devoted to you, speaking words of love and praying for your happiness.

Take the fifth step, that we may serve the people.

I will follow close behind you always, and help you to keep your vow of serving the people.

Take the sixth step, that we may follow our religious vows in life.

I will follow you in observing our religious vows and duties.

Take the seventh step, that we may ever live as friends.

It is the fruit of my good deeds that I have you as my husband.

You are my best friend, my highest guru, and my sovereign lord.

The words of the Saptapadi were traditional. They probably had no more special meaning to the young bride and groom than did any of the other strange and solemn words that had been spoken. But some of those vows my grandparents recited on their wedding day would take on an extraordinary significance for them in their 62 years of married life.

“And oh! That first night. Two innocent children all unwittingly hurled themselves into the ocean of life.”

With those words, written almost half a century later, my grandfather began the account of his wedding night that appears in his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth. “We were too nervous to face each other,” he reported. “And we were certainly too shy. How was I to talk to her and what was I to say?”

Mohandas was 13 and, by his own confession, knew very little about sex beyond a few whispered hints he had recently received from his considerate sister-in-law Nandkunwarben, the wife of his older brother Lakshimidas (there is reason to wonder, given the strict taboo in sexual matters between men and women in Indian families, just how explicit his sister-in-law could have been).

“The coaching couldn’t carry me far,” he wrote, adding that he never knew and never inquired whether or not Kastur had been given any helpful information or instruction. “But no coaching really is necessary on such matters. We gradually began to know each other and to speak freely,” writes Grandfather.

There will always be much that is unknown about the intimate relationship of Kasturba and Mohandas Gandhi. My grandmother left no written records and, in later life she never confided her innermost feelings or personal reminiscences to anyone. But we can, by conjecture, arrive at some understanding of what Ba’s experiences may have been.

My grandmother belonged to a generation of Indian women who were schooled to be patient and passive. But at that moment, with the silence between them growing ever more oppressive, young Kastur must have suspected that Mohan knew even less than she did about what was supposed to happen next. She waited, wondering what she should do — if anything.

And then, as was his habit in moments of crisis, Mohan smiled. It was a smile that in future years would delight his comrades, confound his critics and disarm his enemies. On this night, it dispelled all his bride’s uncertainties.

A good Hindu wife follows her husband’s lead in all things. Kastur smiled at Mohan. They began to speak. Together, they embarked on the adventure of marriage.