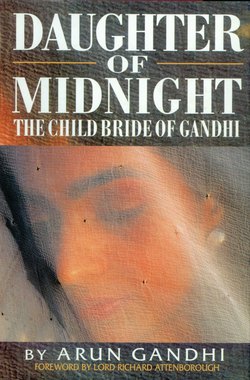

Читать книгу Daughter Of Midnight - The Child Bride of Gandhi - Arun Gandhi - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеAn unknown Eastern philosopher once said: “Nothing can ever grow under a banyan tree.” This is as true of individuals. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s stature was by far more enormous than a banyan tree — it dwarfed everyone else. My grandmother, Kastur, and my father, Manilal, were two who submerged their identities and blended themselves into his image and philosophy.

For those brought up in a modern western society such acts of self-sacrifice in the interest of a person, a programme or a philosophy are difficult to understand and accept. In the eastern society it is the family and legacy that supercedes every other consideration.

Western scholars have, understandably, blamed Mohandas Gandhi for not giving others a chance to flourish or blossom. However, my grandfather had a vision; a world view that transcended the self. Consequently, neither Kastur nor my father ever thought about their personal achievements or accomplishments and preferred to merge their lives into that of my grandfather. The vision, the quest, the world was more important to them than their personal image.

For everyone who knew her, Kastur was always Ba or “Great Mother”, Grandmother. My greatest regret will always be that I did not get the opportunity to know her better. The last time I met my grandmother I was just five years old. This was in 1939. My father, Manilal, her second son, had chosen to live in South Africa to work for nonviolent social and political change, a movement that my grandfather had started in 1893.

Since my father was the only one of the four Gandhi sons to adopt voluntary poverty and devote his life to nonviolence, our family reunions in India had to be judiciously spaced out, on an average of once in three or four years.

For most of us who have grown up in eastern culture the daily affirmation of love, as in western families, is unheard of. Our parents or grandparents never told us that they loved us. They did not have to because their actions and concerns for us conveyed their love more eloquently than words could express. I just knew that the whole family loved me.

Apart from my love for Ba what compelled me to research the life of Grandmother was the fact that the few existing references, or memoirs of those who lived with her, depicted her as an ever-bumbling fool who had no idea what her husband was trying to achieve.

I refused to believe this could be true. It was not my or my parents’ experience. She may not have gone to school and could not read or write much but received from her parents, her parents-in-law and the family, the best upbringing one can hope for. I did not want history to record a negative image of my grandmother. Our painstaking research confirmed that she played a significant role in the struggle for India’s freedom and in the ‘making of the Mahatma’.

Without her unstinted cooperation, my grandfather could not have achieved the spiritual heights that he did. Many a wife has left her husband for much less than what Grandmother was asked to give up. She made the sacrifice not simply because Grandfather wanted her to but because she was convinced it was the right way.

Imagine for a moment the all-too-familiar scenario where a wife refuses to cooperate with her husband in whatever he is trying to achieve. It would, most certainly, lead to domestic disharmony and even a breakup of the alliance. Grandmother never followed anyone slavishly. She followed with conviction just as my father, Manilal, did.

In his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth, my grandfather confesses that he learned the rudiments of nonviolence from my grandmother. She was never passive, nor aggressive, but always stood up for what she was convinced was right and just. When Grandfather was in the wrong she did not argue with him but quietly, nonviolently, led him to the realisation of the truth. That, Grandfather said, is the true essence of the philosophy of nonviolence.

Researching my grandmother’s life was not easy. She wrote very little herself. Her family records, as well as the government records of births and deaths, were washed away in floods that ravaged Porbandar at the turn of the century.

Her parents and her brother died young leaving no written record of family history except for the references in Grandfather’s writings to the Makanji family and Ba.

In our research my wife, Sunanda, and I had to depend on oral history, which was often clouded by the awe-inspiring memories of my grandfather. It was sometimes an exercise in patience and perseverance to keep the interviewee focused on Grandmother. Since 1960 we have recorded interviews with scores of people from all walks of life who knew Ba and had lived and worked with her.

Grandmother’s life story is unusual and inspiring. I hope you enjoy this labour of love.

Arun Gandhi, 1998