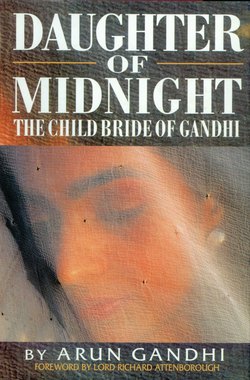

Читать книгу Daughter Of Midnight - The Child Bride of Gandhi - Arun Gandhi - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6

ОглавлениеEarlier that year, in Rajkot, the Gandhi family had faced a tragedy and made a decision.

Suddenly, unexpectedly, in the spring of 1891, Putliba Gandhi became ill. Within days, she was dead. The question arose: should Mohandas be told? Mohandas was devoted to Putliba, closer to her than any of her other children. Would any good be served by notifying him of her death while he was in the midst of preparing for his final law examinations? It seemed best to wait. Time enough to give Mohandas the painful news after he returned to India.

Kasturbai agreed with the decision made by the family. She had been longing for the moment she would see her husband again, dreaming of the day little Harilal could be with the father he had never had a chance to know. But now, remembering how stricken Mohandas had been at the time of his father’s death, she worried about his reaction to his mother’s death and to receiving the news so abruptly at the moment of his homecoming.

Kasturbai herself knew how irreplaceable Putliba’s love and guidance was. Under her mother-in-law’s wing she had felt secure and protected, confident and capable. Without Putliba she was bereft, overwhelmed by sorrow and uncertainty. Wouldn’t Mohandas feel the same? Everyone was expecting so much of him. But would he be able, after so sad a homecoming, to take hold and take charge of a family that was rapidly crumbling?

All Kasturbai could do was to wait patiently for his return. Wait and hope, and prepare to welcome him back into the household in Rajkot.

The family was aware that highly educated young men returning from England with Western mannerisms and dress usually wanted to make changes in the ancient Indian atmosphere of their own households. Anticipating this, Lakshimidas had instructed his wife Nandkunwarben to prepare for Mohandas’ return by purchasing English crockery and fine chinaware to replace the brass thalis (plates) and vadkas (bowls), on which the family meals were customarily served. He also bought chairs so they could all eat at a table, instead of sitting on floors, Indian fashion.

When the S.S. Assam steamed into Bombay’s magnificent deepwater harbour in mid-August, Lakshimidas was waiting on the dock at Ballard Pier. He had travelled alone from Rajkot to meet Mohandas, but as he watched the disembarking passengers, he almost failed to recognise his young, westernised brother in his English outfit. His joy at seeing Mohandas, his pride in his brother’s newly acquired prestige as a barrister was tinged with a slight apprehension.

“Will he ever be able to fit into our eastern way of life?” Lakshimidas asked himself as he moved forward to greet Mohandas.

“How is Mother?” Mohandas inquired at once. But Lakshimidas parried the question, and explained that their friend, Dr. P. J. Mehta, who had been the first to welcome Mohandas to London, was now back in Bombay and had invited them to stay with him for a few days before returning to Rajkot.

That evening Mohandas pursued the question again: “How is Mother?” Lakshimidas knew that he could not ignore the question any longer and broke the sad news as gently as he could.

Writing in his autobiography years later, my grandfather still had difficulty describing the “severe shock” of that moment. “I must not dwell upon it,” he wrote. After acknowledging that his sorrow was even greater than at the time of his father’s death, he added: “But I did not give myself up to any wild expression of grief…. I took to life just as though nothing had happened.”

Lakshimidas suggested that they delay their return to Rajkot — it had been Putliba’s last wish that Mohandas seek readmission into the Modh Vania caste, Lakshimidas said. For three years they had lived with the ban without complaint, but the problem had taken on new import, new reality at the time of Putliba’s death. Her funeral ceremony had been curtailed, certain rituals were omitted, some old friends did not attend — much to the dismay of all who loved her. If that could happen to one so faultless as Putliba, what hope was there for the rest of them? The family also worried that Mohandas’ continued excommunication could cloud his future as a lawyer. Lakshimidas had recently gone to the caste elders in Rajkot for advice, and he now described to his younger brother the procedures he must follow to gain expiation for his forbidden foreign sojourn. Mohandas agreed to comply with the elders’ recommendations, even though caste restrictions were no longer a matter of personal concern for him, and never would be again. He would seek readmission for the sake of his family and to honour his mother, not because of any desire to redeem himself.

Leaving Bombay, Lakshimidas and Mohandas set out on a penitential pilgrimage to Nasik, a holy place about a hundred miles to the north-east. There, before invited witnesses, Mohandas dutifully immersed himself in the sacred waters of the Godavari River for a propitiatory bath. From Nasik, they travelled on to Rajkot for the next step in his rehabilitation, a ceremonial dinner arranged by Lakshimidas and Karsandas. Acting on behalf of their younger brother, they had reserved a hall, ordered food prepared, and invited all Rajkot caste elders to attend. Most had accepted. As a further act of penance, Mohandas himself stripped to the waist and served the dinner to the guests. Though this seemed like nonsense to him, Mohandas was coaxed by his brothers to carry out his part in the ceremony. When the Rajkot elders accepted food from him, it signalled the end of his excommunication.

Kasturbai had counted the hours, waiting anxiously for her first glimpse of her husband. But their reunion, when at last it came, was initially awkward and restrained.

She and Mohandas were both 22; they had not seen each other for almost three years. Much had happened in that period. She needed time to become reacquainted with this stranger of a husband. He looked, dressed, even spoke, so differently from the Mohandas she remembered. He had changed in ways she could not comprehend.

Kasturbai had matured into a beautiful woman. Mohandas realised that at once. He was captivated by his wife’s beauty — as he had always been. Perhaps, after three long years of vigilant self-restraint, three years of monitoring all his sexual desires, even his thoughts, he was more attracted to her than ever before.

How could he have forgotten how lovely Kasturbai was? How enchanting she was to behold! Her smooth skin, her large eyes framed by thick lashes, her tiny figure, shapely and supple as ever under the soft folds of her bright-coloured sari! How beguiling it was to watch her comb her long, gleaming black hair; to study the simple grace of her movements; to hear, at her every step, the musical tinkle of the tiny silver bells that encircled her slender bare ankles. Any man would envy him, enjoying the loving devotion of this proud and beautiful creature. And enjoy it he did, to the full. After the austere and lonely years abroad, he deserved a season of self-indulgence at home before facing up to the responsibilities awaiting him. In his wife’s embrace Mohandas could forget all else.

For Kasturbai, too, the years of yearning were over — years of going to bed alone night after night. Only now that Mohandas was home again did she realise how great her loneliness had been. It was reassuring to know that England had not changed him, at least in one respect. He still found her desirable. She was delighted, too, at the pleasure Mohandas took in their son: playing and joking with Harilal, effortlessly winning the little boy’s devotion as well as other children in the household.

For the next few weeks the whole family seemed joyful and carefree — relieved of pent-up tensions. But after a time, Mohandas began to grow restive. He had welcomed the Western touches the family had provided but now declared this was not enough. He bought English cocoa and oatmeal and asked that porridge be served for breakfast. He told Kasturbai that he had decided their son Harilal would henceforth be brought up like an English child: hardy and tough — as all the Gandhi children should be. He bought shoes for the boys and insisted that they no longer go barefoot. He took the children on long walks into the countryside. He made up a schedule of exercises, and conducted calisthenics classes for them every morning.

Kasturbai said nothing. If he wanted it that way there was no reason for her to protest. In fact, she and her sisters-in-law, Nandkunwarben and Gangaben, were happy to have him take the children off their hands for part of the time each day.

But Mohandas’ zeal for giving instruction grew, and it soon extended to Kasturbai. So once again, to Kasturbai’s dismay, the nightly reading lessons began. But once again, to Mohandas’ dismay, his wife displayed absolutely no interest in the project. Worse still, she seemed to have no understanding of why he considered it so important. Kasturbai’s failure to comprehend the dignity of his profession rankled even more than her failure to appreciate his magnanimous aspirations for her.

Mohandas persisted. Kasturbai resisted. And the days passed. Then other familiar and distressing patterns began to emerge. Mohandas’ unfounded jealousies, unfair suspicions, unjust accusations. Kasturbai’s repeated and unequivocal denials.

Kasturbai was alarmed. Mohandas had not changed at all. They seemed to be picking up the threads of life where they left off years ago, when he was a mere schoolboy. But now he was a barrister. Surely a barrister had better ways to spend his time than teaching his wife to read and write, or keeping track of her every move, or accusing her of indiscreet acts she had neither the desire nor the opportunity to commit.

The whole family was concerned about Mohandas. Kasturbai could tell from her talks with her sisters-in-law. Lakshimidas and Karsandas had planned to support Mohandas financially only as long as he was a student. Now that he had brought his costly English education back to India, they expected him to use it, and assume responsibility for a major part of the family expenses. This had become a matter of increasing urgency because Lakshimidas, the family’s principal breadwinner, had suffered a setback in his own career.

While Mohandas was in London, Lakshimidas had been appointed, through the influence of his Uncle Tulsidas, to an undemanding but remunerative position as secretary to the crown prince of Porbandar. Lakshimidas’ duties had required only occasional trips to Porbandar. His wages had greatly enhanced the family income, and an even more important post seemed to be in prospect when the young prince became the Rana. As it turned out, the heir to Porbandar’s throne was a profligate who, unbeknown to Lakshimidas, had made off with some of the crown jewels from the state treasury. There were questions about this by the new British political agent who had recently arrived in Porbandar. It was a British resident’s duty to prevent local royalty from converting state moneys into private wealth. The young crown prince claimed he had acted on the advice of his secretary. As a result, Lakshimidas had lost the job, the income, and the promise of a better position to come.

Kasturbai knew all about these worries. Yet Mohandas seemed totally oblivious and unaware of any household problems and seemed unconcerned about his obligations to his brothers. He had made no move to seek a suitable appointment, or find a well-paying position or earn any money whatsoever. All his attention was focused on her: Kasturbai. Kasturbai knew the strength of the attraction Mohandas felt for her, but she now wondered if she didn’t also serve as a distraction for her husband. Was he seeking diversion by both their quarrels and lovemaking and ignoring matters of far greater consequence? She realised that the time had come for her to speak up.

One night, in the privacy of their own bedroom, she confronted Mohandas. She reminded him of his debt to his brothers and spoke about the on-going household expenditures. These costs, she pointed out, had increased with their Western innovations, and the changes he had insisted upon. What Lakshimidas needed now was help from him. Kasturbai had never expressed her opinions so openly before. By the time she finished, Mohandas was indignant — indignant and shaken.

The next day, without explanation, Mohandas sent Kasturbai off on the train with Harilal to visit her parents in Porbandar.

“Perhaps only a Hindu wife would tolerate such hardships,” my grandfather wrote many years later, in discussing his relationship with my grandmother during the early decades of their marriage. “And that is why I have regarded women as an incarnation of tolerance. A servant wrongly suspected may throw up his job, a son in the case may leave his father’s roof, and a friend may put an end to the friendship. The wife, if she suspects her husband, will keep quiet. If the husband suspects her, she is ruined. Where is she to go? And I can never forget or forgive myself for having driven my wife to that desperation.”

I also admire my grandfather’s forthright (and oft-repeated) admissions of his own offences as a jealous and domineering husband. But I believe his portrayal of my grandmother’s reactions to this jealousy and domination may have been distorted by his urgency to condemn his own shortcomings. Indeed, we find that Bapu has done Ba a disservice in his autobiographical writings by his frequent depictions of her as ever meek and submissive. Such characterisations of Ba have been widely accepted and repeated by Gandhi biographers. But in my view she was never as spineless and long-suffering, as tolerant of abuse, as altogether helpless and desperate, as Bapu (and his biographers) would have us believe. That she may sometimes have appeared to be so was due more to the circumstances of her life than to the nature of her temperament.

I base this conclusion on my own memories and on the recollections of others who knew her well and on my grandfather’s correspondence with the family. Speaking apparently from experience, he sometimes cautions against incurring Ba’s displeasure. In a long letter written to my father from a South African prison in 1909, for example, Bapu advises 16-year-old Manilal, who was temporarily in charge of farm and family matters at Phoenix Settlement, on everything from household finances, to diet tips, to recommended readings, and counsels him to “cheerfully bear Ba’s ill temper”.

In truth, it was Kasturbai, not Mohandas, who had learned how to bear a spouse’s ill temper, and to do so cheerfully. Certainly this must have been the case in that autumn of 1891 when she was “banished” to Porbandar shortly after Mohandas’ return from England. To Kasturbai, the trip would have seemed like a holiday. She was eager to see her parents again and have them see their grandson. Visits had been difficult during the years of Mohandas’ absence, but now, with the excommunication ban lifted there were no household complications. Travel between Rajkot and Porbandar was simpler now, too, since the railroad had come to Kathiawar. She had sensed that Mohandas’ main problem was with himself, not her. A short vacation, a separation, would give him breathing space — time to think about his future, perhaps do something about it, and to get over his displeasure with her. She was confident he would insist on her early return, and all would be well.

Kasturbai was not surprised, therefore, when Mohandas sent for her within a month after her departure. (Or, as Mohandas reported in his autobiography, “I consented to receive her back only after I had made her thoroughly miserable.”)

She and Harilal returned happily to Rajkot where she found, to her satisfaction that things had changed for the better. No more lessons, no more suspicions, no more quarrels, and only a new seriousness between them. And a new tenderness on Kasturbai’s part, as she learned more of her husband’s true worries and insecurities.

Mohandas confided his fears to Kasturbai one night, not long after her return from Porbandar. She listened attentively, though his explanations seemed addressed as much to himself as to her. He had now turned his full attention to getting started in his career, something he admitted he had been avoiding. He had explored the idea of starting a practice in Rajkot, but he felt he would be inviting ridicule if he did, and for good reason — in spite of his three years of study in England, he felt unqualified to practice law in India.

“Who will be fool enough to employ a person like me,” Mohandas asked. “One who doesn’t even have the knowledge of a law clerk?”

Although he was well versed in the Common Law, well read in Roman Law, he knew nothing whatsoever about Hindu and Muslim Law. A home-trained vakil, or law clerk, such as his brother Lakshimidas, was far more familiar with Indian law, yet he, as an English-educated barrister, would normally be expected to charge fees ten times as high as a vakil. That, he declared, would only add the sins of arrogance and fraud to his offence of ignorance.

Kasturbai consoled him as best she could, and beseeched him to tell his brothers of his misgivings and seek their advice. He had done just that, he said. And then he disclosed his plan. He and Lakshimidas had agreed that he should go to Bombay for a time. There were already too many lawyers and not enough cases in small provincial towns like Rajkot and Porbandar. But in the city of Bombay there would be many opportunities. There he could study, become acquainted with Indian law, gain some much-needed court experience, even earn some fees. He would set up a household there, he said, but to save on expenses, Kasturbai and Harilal would have to stay in Rajkot for the time being. They might perhaps join him later.

Again, they were to be separated. But now Kasturbai fully understood why this was necessary. In Bombay, Mohandas could fulfill the family’s dream and become a successful advocate.

A few weeks later, when she sent her husband off to the city to seek his fortune, Kasturbai gave him her good wishes. But she did not give him her news. Only when he was more settled, and when she was absolutely certain it was true, would she let him know that she was pregnant again.

For Mohandas, he was still feeling uprooted after the years in London, still unsure of his own abilities, still grief-stricken because of his mother’s death, (and still guilt-ridden, it would seem) by a memory of the circumstances of his father’s death. This was coupled with his inability to free himself from what he called the “shackles of lust” — the next six months of his life were bleaker than any he had ever known. In Bombay he found only discouragement and disenchantment.

He rented rooms and hired a cook — a man so incompetent that Mohandas ended up doing most of the cooking himself. He bought some law books, he studied the Civil Procedure Code and the Evidence Act, and every day he walked the several miles to and from the High Court where he observed the great and famous Bombay lawyers at work. But the court proceedings were so dull that he often fell asleep.

Meanwhile, his brothers were still paying all his expenses, his debts were mounting each month, and a letter from Lakshimidas had brought unexpected news. Kasturbai was expecting another child, my father, Manilal.

This was cause for rejoicing, of course, but it also increased Mohandas’ crushing sense of responsibility. One more child, one more soul to look after. Now, more than ever, he must earn money. But the weeks passed, and Mohandas remained a briefless barrister. As a stopgap measure he applied for a part-time position teaching English at a boys’ high school. The salary listed was only 75 rupees a month, but that was better than nothing. He did not get the job. The school, he was told, hired only graduates of Indian universities. His London Matriculation degree with Latin as his second language did not qualify him for a teaching post.

Then, at last, a petty court case came his way — and without his paying a commission to a tout. Mohandas proudly donned his barrister’s wig and gown for the first time, and appeared for the defendant in a simple case in the Small Claims Court. But when he rose to cross-examine the plaintiff’s witnesses, his old fear of public speaking overcame him. He could not think of a single question, could not utter a single word. A ripple of laughter ran through the courtroom. Humiliated, Mohandas sank into his chair. He advised his poor client to hire another lawyer, refunded the fee of 30 rupees paid in advance, and fled from court, resolving then and there to take no more cases until he had courage enough to conduct them (not until he found himself in South Africa would he find that courage).

Finally, the word came from Rajkot. Lakshimidas could no longer afford to pay Mohandas’ expenses. He urged Mohandas to leave Bombay, return home, and try his luck in Kathiawar, even if it meant doing clerical work. Lakshimidas, himself a petty pleader, could give him some applications and memorials to write, to get him started.

With defeat looming large, Mohandas boarded the train, left the city, and returned to Rajkot to face a joyfully expectant Kasturbai.

The second son of Kasturbai and Mohandas Gandhi, was born in Rajkot on October 28, 1892 — an event I find noteworthy because this child (named Manilal), would grow up to become my father. Manilal’s birth was celebrated with the customary religious festivities. Sweets were distributed; ceremonies performed; gifts received.

Kasturbai visited the temple to give thanks. The arrival of another healthy son was a good omen — a harbinger of better times.

All her concerns for her husband, all the anxieties she had felt over the past many months, were forgotten. Their life seemed to be settling into a comfortable pattern. Mohandas was home in Rajkot, he had opened his own office and was writing enough petitions and memorials for Lakshimidas and his vakil friends, drafting enough briefs for other barristers, to earn the 300-rupees-a-month income that had evaded him in Bombay. For Kasturbai this was success enough. She was no longer beholden to her in-laws. Harilal was lively as ever, Manilal was a calm and lovable baby, and she was content, happier than she had been for years.

But what was contentment for Kasturbai soon became frustration and disillusionment for Mohandas. An embarrassing altercation in the early spring of 1892 left him at odds with his brother, affronted by British officialdom, and chagrined to realise how ignorant he was of the ways of the colonists.

The incident occurred when Lakshimidas, still out of favour with the new British resident in Porbandar because of the crown prince’s misdeeds, persuaded Mohandas to undertake a delicate mission. Lakshimidas learned that Mohandas and this officer, a Mr. Charles Ollivant, had met socially in London once or twice under friendly and agreeable circumstances. As a British administrator on furlough from service to the Empire and about to take up new duties in Kathiawar, Mr. Ollivant had enjoyed conversing with a student from Rajkot. Now Lakshimidas, hoping to regain a place of influence in Porbandar, asked his younger brother to use his influence with his English friend.

Mohandas was reluctant. “It was a trifling friendship,” he told Lakshimidas. “It should not be used for such purposes.

Lakshimidas disagreed. ’You do not know Kathiawar. Only influence counts here. It is not proper for you, a brother, to shirk your duty when you can clearly put in a good word about me to an officer you know.”

This was his older brother’s first request for help of any kind, and Mohandas did not have the heart to decline. Mohandas made the trip from Rajkot to Porbandar and presented himself once again as a supplicant at the door of the British resident.

Predictably, Mr. Ollivant was rude. When Mohandas, after mentioning their meeting in London, began to explain the purpose of his visit, the political agent interrupted him. “Surely you have not come here to abuse our acquaintance,” he said.

Mohandas tried to continue, but Mr. Ollivant interrupted again. “Your brother is an intriguer,” he barked out. “He can expect no more work from Porbandar. If he has anything to say to me let him apply through proper channels.” He asked his caller to leave. “Please hear me out,” Mohandas tried to protest But Mr. Ollivant called a servant and ordered him thrown out — bodily.

Shamed and outraged, Mohandas immediately wrote out a demand for an apology, threatening legal action if it were not forthcoming.

Ollivant’s reply was curt and final. “You are at liberty to proceed as you wish.” But in British India, as Mohandas well knew, the only court of appeals in a princely state such as Porbandar was, of course, the British resident.

Mohandas returned to Rajkot and told his older brother of this latest fiasco. Lakshimidas was grieved. But Mohandas remained aggrieved. He had been physically assaulted! English law should not permit such arrogant abuse of authority! He consulted other lawyers, wondering if he had any recourse. They advised him not to pursue the matter, to do so would mean his ruin. They said he was still fresh from England, still hot-blooded. He did not understand life in his own country. Such incidents were common, they told him. To get along in India, he must learn to pocket the insults of the British officers.

My grandmother knew of Grandfather’s many disappointments and disillusionments. What was there to say? There clearly was no place for him in the petty politics of Kathiawar. He would never follow in his father’s footsteps and become the dewan of Rajkot or Porbandar. Such a dream was no longer attainable, nor was it worth seeking. Even a ministership or a judgeship seemed unlikely for one as inept as he was at playing the local games of intrigue. And his Bombay experience had put his future as a barrister in question.

To Grandmother, to the family, to Mohandas himself, his career appeared to be ending before it began. His failure seemed complete.