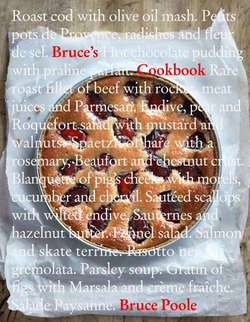

Читать книгу Bruce’s Cookbook - Bruce Poole - Страница 27

ОглавлениеRillettes of duck and some thoughts on confit and duck fat

The first time I ate decent rillettes, it was a revelation. How any chef worth his or her Maldon can go for long periods without wanting to make them is beyond me. Rillettes made from duck, pork, guinea fowl or rabbit are equally good and, once sealed in a Kilner jar or somesuch, will keep for months, which only increases their culinary value, in my book. The word rillettes, by the way, is the French term and hails from the city of Tours in the Loire valley. Potted duck would be the English equivalent, but as the method of salting and cooking the duck slowly in its own fat is distinctly and brilliantly French (this is the great ‘confit’ after all, one of French gastronomy’s most treasured gems), it seems apposite to use the correct terminology here. Since this dish keeps very well and the process takes a couple of days, it is daft to make it in small quantities. In addition, duck confit is a superb dish in its own right, so definitely the more duck legs, the merrier (see Duck Confit with Pommes Sarladaise).

This recipe calls for far more duck fat (to cook the legs) than actually ends up in the rillettes themselves. This is a very good thing, as the leftover fat (which will have become beautifully infused with the garlic and thyme) is the perfect vehicle for sautéing and roasting all manner of things – particularly potatoes. It can also be re-used to confit more duck, but bear in mind that each time it is used for this purpose, the fat will take on some of the salt from the legs. There will come a time when it becomes unusably salty and at this juncture it is fit for nothing, so do not attempt to use the same fat for duck confit more than three or four times. However, once the fat is sealed in an airtight container, it will keep almost indefinitely. I have a large jar at home (in which I confit the Christmas turkey legs) that is three years old and still going strong. Although its preserving properties are waning (as explained above), it remains just the ticket for the Sunday roasties.

So, if attempting this recipe – and I urge that you do, almost above any other in the book – it is best to bite the bullet, climb on the duck-fat-bandwagon and stock up your larder. Conveniently, good delis and the better supermarkets now stock duck or goose fat in handy, baked bean-sized 350g tins.

Serves lots as a starter – makes about 1.5 litres

6 large (French) duck legs – about 350g each (or 10 smaller English duck legs, such as Gressingham)

50g sea salt

1 whole head of garlic

1 big bunch of fresh thyme

6 bay leaves, roughly torn

at least 1.5kg duck or goose fat, possibly more depending on the dimensions of your pan

½ eggcup of black peppercorns

freshly ground black pepper

The day before you cook the duck, place the legs in a roomy container and rub the sea salt well into the meat on both the skin and flesh sides. You may think this is a lot of salt, but worry not. Split the garlic head widthways with a heavy knife and break it up with your fingers to separate the cloves. Add them, skin and all, to the duck legs. Add the thyme and the bay leaves. Mix well, cover and refrigerate overnight.

The following day, set the oven to 130°C and select a suitably capacious ovenproof pan with a lid – a big Le Creuset is ideal. The legs need to fit in it comfortably but snugly, as they will be totally submerged in the fat as they cook. If the pan is too small, they will not poach in the fat properly; if it is too big, you will end up needing even more fat to cover them.

Briefly rinse the salt from the legs under a cold running tap (discarding the salt) and dry them thoroughly on absorbent kitchen paper. Empty the contents from the tins of duck fat into the empty pan. Pick out all the garlic, thyme and bay leaves from the marinade and add these aromatics to the pan together with the peppercorns. Add the duck legs and bring the whole lot up to a gentle simmer on the stove. As the fat melts, the legs will settle and should end up totally submerged. If they are not submerged, you will need more fat – this is why it is worth erring on the side of generosity when you purchase your duck fat in the first place.

Cover with the lid and cook in the oven for 2½–3 hours. The meat should be loosening around the leg bones when ready, but it should not be falling apart. If the meat still feels hard and tight, give them another half an hour. Remove the pan and leave it to cool significantly but not completely. Leave the lid on as the confit cools.

When the meat is at a temperature at which it can be comfortably handled, but is still warm, lift the legs from the fat and place in a tray. Strain off the remaining fat and keep, throwing away the cooked aromatics. With scrupulously clean hands, carefully pick all the meat from the bones, paying particular attention to removing the nasty, needle-like cartilage. The cooked skin is lovely and should on no account be chucked out, although it is not required for the rillettes. (It is great pan-fried or baked on a rack in a low oven until crisp and used in warm salads.) On a big chopping board, pull the duck meat apart using two forks, or simply chop up with a heavy knife. Try not to eat too much of the duck at this stage or a proportion of your carefully sourced Kilner jars will soon become redundant. How smooth you like your finished rillettes is a matter of personal choice and it is this chopping or ‘stripping’ stage that will determine the final texture.

Add the chopped or shredded duck to a large china bowl and gradually beat in the still-warm, strained duck fat, slowly at first as if you are making mayonnaise. At this stage you need to give it some serious welly with a wooden spoon, as you want the fat to bind with the meat – use your fingers if it helps. Avoid the food processor, as this will lead to an oversmooth and pasty finish. The flat paddle on a food mixer (such as a Kenwood) is useful here, but I prefer doing it by hand. You will need to add approximately half the volume of fat as meat, which seems like a ridiculously large amount (and it is), but it is this copious fat content that adds the necessary degree of delicious luxury to the rillettes. It is vital to get the seasoning right at this stage. If the legs were adequately rubbed in the first place, it may not require any additional salt, but probably will. Plenty of pepper is a must.

As the mixture cools, beat it every few minutes to prevent the fat separating from the meat. When it is almost completely cold, store in sealable containers – old-fashioned Kilner jars are perfect for this. This recipe makes about 1.5 litres in total so choose your storage jars accordingly. Make sure there are no air pockets in the jars and reheat some of the remaining fat if it has solidified, in order to pour a 5mm layer over the top to seal the rillettes before closing the lid.

This will keep for months in the fridge, but once opened needs to be consumed within a week or so. For this reason, if you are buying jars especially for the job, it is better to buy several smaller jars rather than one or two bigger ones. Eat with crusty brown bread or toasted brioche and a green salad, or cornichons. There is much conjecture as to what temperature the rillettes should be when eaten, with some foody stalwarts snottily eschewing any that are not served at room temperature or even warmed slightly. Personally, I find this only exaggerates the inherent fattiness of the dish and I am happy to risk the accusation of heresy by stating my preference for them served straight from the fridge, or at cool larder temperature. Amen.