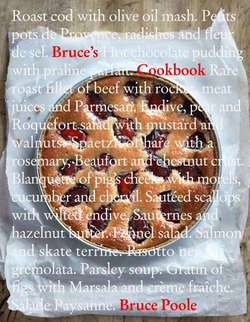

Читать книгу Bruce’s Cookbook - Bruce Poole - Страница 28

ОглавлениеPork terrine with (or without) prunes

If I am dining in a decent restaurant and see pork terrine on the menu, I simply have to order it. There may be other things that catch my eye and it might be that my mood/appetite/the weather dictates the additional summoning of a shellfish or salady starter. But the terrine has to be tasted. A good terrine requires timing, skill, judgement and, of course, taste. It is not, contrary to what one often reads, easy to make well, but when just so, it is unspeakably delicious. And unlike some other time-consuming and ‘technical’ dishes I could mention, the considerable effort and time put into preparing, cooking and serving a decent terrine is in direct proportion to the pleasure derived from eating it. In short, it is worth the effort and there is much point to the whole process. For this reason I feel that a magnificent terrine should be left to stand alone so that it can be savoured without the interruption of unwanted garnishes. A few dressed, crisp green leaves perhaps; or some cornichons and grain mustard maybe; some crusty bread or toast with fresh butter certainly, but that’s it. Save your chutneys and fancy vinaigrettes for dishes that need the bolster; this doesn’t.

I hope it goes without saying that the better the meat, the better the terrine. For this dish at Chez Bruce we use the superb pork from Richard Vaughan’s Middle White pigs, which are reared on his achingly beautiful farm near Ross-on-Wye in the Welsh Marches. Richard describes the meat provided by these happy pigs as ‘the Chateau Lafite of pork’ and he’s not wrong. I have visited Richard and his lovely wife Rosamund (who, as well as being an ace cook, plays the piano to concert standard and speaks fluent Arabic – in short, a talented lady) on several occasions and have wonderful memories of Huntsham Farm. In fact, another visit is surely due.

Makes 1 big terrine to serve 10–12 comfortably as a starter (any leftover mixture can be fried in small patties for the best-ever pork burgers)

1 large onion, peeled and finely chopped

2 cloves of garlic, peeled and finely chopped

3 bay leaves

75g unsalted butter

300g pork fillet, trimmed

500g pork shoulder, without rind

375g pork belly, without rind

200g pork liver (or chicken liver)

125ml decent dry white wine

15–20 fresh sage leaves

½ bunch of fresh thyme, leaves picked and chopped

fresh nutmeg

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

about 20 thin slices of Italian lardo, or back fat, or 24–30 thin slices of pancetta (pre-sliced stuff from supermarkets is ideal for this)

about 12 pitted Agen prunes, ideally macerated in Armagnac (optional)

It is acceptable and much quicker to pass the meat, roughly chopped, through the coarse blade of a mincer (if you have one). However, never one to take a short cut for the sake of it, I feel the texture of this terrine is improved considerably if all the chopping is done by hand. For this you will require a very big board, a very sharp, large cook’s knife and plenty of patience, as it is time consuming. A smaller (equally sharp) knife is also useful to remove the occasional piece of subcutaneous gristle. You will also require one large terrine dish, measuring 28cm long by 11cm wide (at the top) by 8cm deep – number 28 in Le Creuset parlance. (A second terrine dish the same size is also useful but not essential for the weighting process – see later.) Also, a baking tin in which the terrine will sit comfortably, ideally about the same depth as the terrine dish. A large china mixing bowl is also a must.

Make sure the white wine you use is of the good dry kind (Chablis or a dry Riesling is ideal). The chopping process will take up to an hour, so open the bottle at the beginning and taste it often as you work if this helps to lessen the ennui.

Sweat the onion, garlic and whole bay leaves in the butter in a medium pan – 10 gentle minutes should do it. Take off the heat and reserve. Start chopping the meat. The fillet is a tender cut and can, therefore, be chopped into big (1cm) cubes – add to the bowl. The shoulder and belly will need chopping much more finely – you are aiming for dice of approximately 2–3mm here. This will take some time and it will be obvious when you come across any gristle, as it will be impervious to the knife’s pressure – discard it when you do. You may feel that the proportion of fat to lean meat is high, but this is as it should be. Lastly, chop the liver finely and add to the mixture. When the fillet, belly, shoulder and liver have been chopped and added to the bowl, you may need to take a breather and a slurp of wine. Set the oven to 130°C.

Remove the bay leaves from the onion and keep to one side. Add the cooked onion and garlic to the meat, together with the wine, sage, thyme and a generous grating of nutmeg. At this stage, wash your hands thoroughly and mix the whole lot using your hands. Wash and dry your hands again and season the mix well with sea salt and pepper. This seasoning process is essential. Take a small, flattened, walnut-sized piece of the mixture and fry gently in a little butter in a small non-stick pan. Leave it to cool and then taste. Adjust the seasoning accordingly, remembering that the terrine will be served cold and will benefit from being highly seasoned.

Line the terrine dish with the thin slices of lardo or pancetta. Lay the slices in the dish neatly and slightly overlapping with a generous overhang. The idea here is that when the terrine dish is full of mixture, there is enough over-hang to meet comfortably at the top, thereby sealing the mixture. Spoon the mixture into the dish, pushing it down firmly into the corners with the back of a spoon. When you have half-filled it, gently push in a line of prunes along the centre, if you are using them. Continue to add the mixture, making sure that you completely fill the terrine dish to the top. Collect the excess lardo or pancetta to meet at the top neatly. Place the three reserved bay leaves gently along the top of the terrine. Cover the surface of the terrine dish tightly in foil and make four or five small holes in the top through which steam may escape.

Place the terrine in the baking tin, three-quarters fill the tin with boiling water and place in the oven. The precise cooking time will depend on the dimensions and shape of your terrine, but should take in the region of 1 hour 40 minutes. To test, remove the tin carefully from the oven. Take off the foil top (watching out for escaping steam) and insert a clean skewer into the centre of the terrine. Keep it there for 5 seconds and then hold to your bottom lip. The skewer should feel distinctly warm, but not uncomfortably hot. If it is still cold, or barely tepid, re-cover with the foil, return to the oven for another 15 minutes and then test again. Once cooked, remove from the oven, and set the terrine aside with the foil intact and allow it to return to warm room temperature. This will take a couple of hours.

At this stage, you can if you like simply put the terrine in the fridge overnight and it will be terrific as is. However, for a slightly cleaner appearance (without the risk of any crumbling when sliced), it is better to add some weight to the top of the terrine as it chills overnight. For this you require a tray on which to sit the terrine and a piece of hardboard or heavy cardboard cut to the same dimensions as the top of the terrine. (A second, identical, empty terrine dish is ideal.) You will also require a fair bit of space in your fridge for the Heath Robinson balancing act that is about to follow. Place the card/hardboard or empty terrine dish on top of the terrine. Put a couple of heavyish tins, such as baked bean tins, on your card/hardboard or in the second terrine dish and transfer the whole lot to the fridge. It might be a good idea to wedge something suitable either side of the contraption to prevent the weights shifting from their precarious perch above the terrine. Shut the fridge door and say goodnight.

The following day I promise you will wake with such excitement that you may surprise yourself by the manner in which you positively leap out of bed. You will leg it downstairs, perhaps still undressed, to look at your handiwork. To unmould the terrine, run a thin, pointy blade between the side of the dish and the terrine, taking care not to pierce the terrine itself. Have a small board slightly bigger than the terrine handy and invert the terrine dish on to the board. I then pick up the whole board with the upside-down terrine dish still on it, place the thumbs of both hands on the bottom of the terrine to keep it stable and shake the whole lot like crazy. This usually does the trick and the terrine should gradually ease itself on to the board with a pleasing schlopp of released pressure. There will be a fair amount of pink jelly too: lovely, savoury and semi-solidified juices – keep this.

Wipe the terrine dry with absorbent kitchen paper and carve yourself a slice with a long, sharp knife. You may need to get dressed and wait a few hours before serving the rest to your guests.