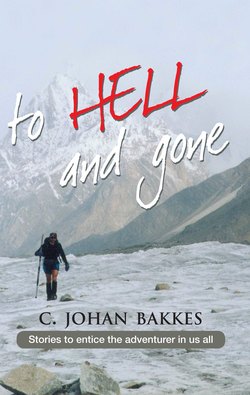

Читать книгу To hell and gone - C. Johan Bakkes - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAnd I told him . . .

And I told him: “Fuck off!” He stood around sheepishly, saliva drooling from the corner of his mouth.

“Fuck off, shoo, go away, bugger off!” And from his threadbare pocket he produced two dry heads of maize and placed them on a used paper plate next to the fire and shuffled misshapenly into the bush . . .

Kalie is a farmer, and a successful one too. That was why he and I were able to bum around in Barotseland, Western Zambia, in an expensive air-conditioned 4x4. We did this often, the two of us.

Barotseland is probably one of the poorest parts of Africa that I have ever visited. It’s understandable, actually, for the Litunga, the king of the Balozi, who inhabit these parts, refuses to accept the authority of Lusaka. Kaunda and his successor, Chiluba, have therefore deliberately disinvested in the region. But it is rich in natural beauty, with the mighty Zambezi River rising here, and winding its leisurely way across flood plains to the sea.

Barotseland is to hell and gone, and a lack of infrastructure and the war in Angola have caused efforts at tourism and development to fail. Empty lodges and holiday resorts are the order of the day. One is struck, however, by the friendliness of the people and, despite the poverty, the absence of typically African beggars, with hands reaching out hopelessly at passing wealth.

Our vehicle was loaded with fine food and cold drinks. We drove through the destitution in style.

All efforts at farming seemed doomed here. The mahango and maize fields stood cropless and shrivelled.

Kalie remarked: “Modern technological development and Africa will probably never find each other. Not even a mighty river with more water than all the South African rivers put together is capable of making its people win the battle against drought.”

Actually I was fed up with Kalie. He had brought along bags of sweets and Boxer tobacco to distribute to poverty-stricken Africa. Personally I don’t believe you can save Africa with sweets. You only spoil the people and teach them to beg. Livingstone and his band of missionaries buggered up Africa’s equilibrium like that. I had taken charge of the sweets, and the tobacco was coming in handy because my own supply of smokes was depleted.

I must admit, however, that the poverty was shocking. Every ragged child held a piece of dried maize in his hand, with which he attempted to appease his hunger kernel by kernel. It was the daily ration, we learned.

We travelled deeper into the bush. After we had crossed the Zambezi by ferry, we emerged on the flood plains. These plains are beautiful – devoid of trees and with waving grass as far as the eye can see. The water was rising and the Balozi traditionally move to higher ground around this time.

We pitched camp under a stand of trees. We settled in. Arranged tables and chairs. The fire was stacked high. Drinks were poured and, while the African night engulfed us, we spoke about adventure, about enjoyment and being privileged, about poverty and begging. That was when I shat on Kalie about the sweets.

Snug under my mosquito net, I gazed at the stars and dozed off.

I got up early and started the coffee. Then he came walking through the bush. Perhaps “walking” is not the right word – “shambling” is a more accurate description.

Scarecrow-tattered, face distorted in a spasm, hand lamely deformed. Laughing inanely, he stood there, mumbling incoherently. Not a welcome sight for any traveller on an empty stomach.

I’ll get rid of him quickly, I thought, and shoved a bag of sweets into his hand. “Thank you, goodbye, sela gabotse, auf Wiedersehn,” I waved him on his way.

Foolish and retarded, he raised his semifunctioning hand and shuffled off into the bush, mouth gaping.

As I was lighting my pipe with relish, steaming coffee in hand, he was back again. And I told him: “Fuck off!” And he placed a two-day supply of his own food in front of me and fucked off.