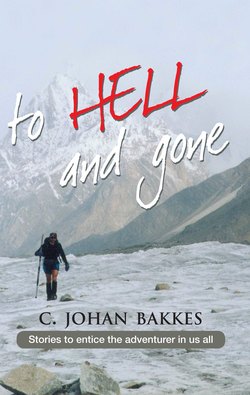

Читать книгу To hell and gone - C. Johan Bakkes - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHell on earth

“This is becoming a dangerous situation,” muttered Brook Kassa, giving me an anxious look. He tried to start the Land Cruiser, but nothing happened.

It was like something from a nightmare or a Freddy Krueger movie. The vehicle was surrounded by a milling, pushing, grinning, gesticulating, shouting horde. Aggression flashed from their sharpened teeth and they waved their AK47s wildly. They were the Afar people from hell on earth . . .

Hell on earth? The expression means different things to different people. To some it’s in their job, their relationships, or a loss they have suffered. By the grace of God I went in search of mine physically.

It started years ago. My search for those “different” places, where few people care to go. The adventure, the moment itself and returning to tell the tale.

In 1999 my daughter and I stood on top of Kilimanjaro, the highest point on our continent. Where is the lowest point? I suddenly wondered as I stood gasping for air.

Bits of information were subsequently gathered here and there. The answer was the Danakil desert – in the north of Ethiopia, bordering on Eritrea and Djibouti.

Not much information is available on the Danakil. Documents that were found described it as:

“The most inhospitable place on earth.”

“The warmest place on earth inhabited by man.”

“The lowest dryland on earth.”

But no detailed description of how, where and what. Travel guides on Ethiopia and Eritrea barely mention the area. Nowhere could I find directions for the journey to hell on earth.

That was enough for my friend Kalie Kirsten, wine farmer on the outskirts of Stellenbosch, and me. We wanted to go there, to visit Ethiopia, its churches, its castles and the Lost Ark of the Covenant as well.

But no one in Ethiopia was willing to go to hell!

“We will take you to the edge of the Danakil, the Afar will take you further – hope you enjoy it,” was the best any tour guide was willing to do. And the two of us, accompanied by Roland Berry, an ophthalmologist, and Paul Andrag, another wine farmer, set off for Ethiopia . . .

“We cannot go further, the salt crust will break and the vehicle will disappear.” I looked at my friends despondently. It was 40 degrees Celsius and we were 120 metres below sea level – about five kilometres away there was a dark spot on the pan: the salt mines of the Danakil . . .

With Brook Kassa, our Asmara guide from Addis Ababa, behind the wheel, we had left the Ethiopian highlands at Angula. During the descent down the escarpment we encountered camel caravans carrying blocks of salt to Mekele. The salt mines were our destination. To my knowledge, this is one of the few caravan routes of the ancient world that still exist. The ivory, silk, spice and slave routes lapsed into disuse a long time ago. How long these salt caravans will still continue, is an open question. It’s a lifestyle for the Afar, the people of the Danakil. It’s hard to believe that it can be economical. A block of salt is sold for 10 birr (about R10) at the market in Mekele. A young, strong camel can carry 16 blocks – the journey to the market and back takes eight days.

The Afar is a proud nation, extremely jealous of this piece of desert. Outsiders are regarded with suspicion. The Habushas (the collective name for other Ethiopians) deem it reckless to travel through Afar territory. Sir Wilfred Thesiger, the first Westerner to traverse the Danakil as late as 1934, wrote: “The Afar invariably castrated any man or boy whom they killed, removing both the penis and scrotum – an obvious trophy – and obtaining it gave the additional satisfaction of dishonouring the corpse . . .”

At Berhale we made a stop. It is a godforsaken, windswept settlement on the banks of a broad, dry river bed. It was sweltering, and people took refuge in hessian dwellings. The most beautiful girls peered around the corners. We photographed them secretly.

If we wanted to continue, we would have to take along an Afar representative. We already had an envoy from the Tigre tourist bureau in Mekele in the vehicle. The provincial government wouldn’t allow us into the Danakil without a monitor. The Cruiser was packed to the brim as we made our way down a dry tributary.

We were no longer driving on a road, but over boulders and river stones. Brook had grown pale beside me. The deeper we went down the dongas and ravines, the more I realised the risk we were taking. No one should venture down here in one vehicle only. A mechanical breakdown could result in death. As Brook came to understand his error in judgment, he developed the runs and kept disappearing behind a rock.

Then the mountains opened up and we burst out on a basalt plain. The wind gusted and warm dust poured in everywhere. These were truly the gates of hell. Suddenly we saw a small gazelle in the distance. It was the Penzeln gazelle. It is found only in the Danakil, and I realised how privileged I was to be one of the few travellers ever to see this rare antelope in the flesh.

We were thoroughly fed up with bouncing and jostling, so in the late afternoon we made Brook stop. We pitched a windswept camp beside a small, warm stream. We submerged our cool drinks, water and beer in the tepid water. While the Askaris were preparing our meal, we lay in the water, ruminating about the day.

Late that night, with mosquitoes and desert bugs of uncertain origin chewing at us, a camel caravan silently joined our camp.

We loaded our equipment. It was only a few more kilometres to sea level. It was not light yet, but we were already pouring with sweat. There was an apprehensive excitement in the air. When we hit “ground zero” according to the GPS, we cheered uproariously.

Then, as far as the eye could see, there was a pan. Makgadikgadi, my arse – it extended almost to the Red Sea. Apparently it’s the remainder of a large inland sea that has evaporated. It was once part of the Red Sea but was isolated by volcanic eruptions about 10 000 years ago.

We stopped at Arho, a small settlement at the edge of the rift valley. It is the hottest place on earth inhabited by humans. The salt miners from hell.

The Afar glared at us suspiciously. The man from Berhale explained why we were there and handed out quat – a narcotic leaf chewed by the Ethiopians. We negotiated for the camping equipment to be left there, thus making the vehicle lighter for the trip across the salt flats. If we broke through the crust, our vehicle, and we along with it, would disappear for ever . . .

We had progressed about two kilometres across the pan when the realisation dawned – we could go no further!

Will we have to turn around? I wondered, staring despondently at the dark patch on the distant horizon. The sun was hot and white.

“I’m walking,” I said and grabbed a water bottle.

And so we set off. It soon became a struggle through salt and water. It grew hotter and hotter. The glare of the sun was blinding. Like an automaton I continued, my eyes fixed on the dark patch up ahead.

After a while I became aware of a strange noise, almost like the sound of the seals at Cape Cross, and I realised it was the bellowing and moaning of a multitude of camels. The mine was within reach and we pushed on with renewed effort. The water was growing considerably warmer . . .

And then I walked into another world. It was almost unreal. As if I found myself in a scene from the Star Wars underworld, or a medieval nightmare. In the stifling air, amid more than two thousand camels, wild men with sharpened teeth, dressed in tattered clothing, were carving blocks of salt out of the earth’s crust with antiquated tools. There was hustle and bustle and shouting and bellowing. The glaring sun, the mirages and the heat lent to the scene an aura of science fiction.

The envoy from Mekele explained that the miners arrived at the mine from Arho with their camels in the morning, when it was still dark; at night, when it was slightly cooler, they returned with the yield of the day on their camels’ backs.

We took photographs.

Before long the Afar guide began to gesticulate uneasily. He pointed up and then down. We didn’t really understand, but he began to walk back in the direction of our vehicle, invisible in the distance somewhere near the edge of the pan. It was a distance of about five or six kilometres. Halfway there I realised the danger! The increased temperature of the salt water was almost unbearable. When my sandals were sucked into the salt, I could literally feel my feet boiling. It became a mad rush to escape from the jaws of the devil.

With every suction, my feet were scorching. The last twenty metres were pure hell. We realised if we had left the mine half an hour later, we would have been burned to death on this pan one by one . . .

“This is becoming a dangerous situation,” muttered Brook Kassa as the Afar of Arho crowded round the vehicle. They refused to let us go. What had we come here for? Who were we to want to escape from the underworld? If your road takes you to hell, and the angels of darkness get their hands on you, you can’t just presume that you will be allowed to return!

And then the engine fired, and with a roar we burst through the milling mass – back to the light.