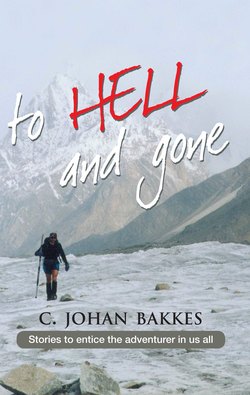

Читать книгу To hell and gone - C. Johan Bakkes - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеUhuru

Were these drops of blood on the snow and ice in front of me? The steamed-up dark glasses were deceptive, for here and there I saw patches of green grass dancing in front of my eyes. The small cracks in the ice looked like bottomless crevasses as I forged ahead like an automaton. One, two, three shuffling steps; rest for ten counts. I no longer remembered why I was here.

“Is someone bleeding?” I croaked. “I think it’s red cool drink,” came a voice from above. I didn’t look up. I could just see the tips of Cara’s boots stepping in her father’s tracks. “How are you, Pa?” my fourteen-year-old asked with shuddering breath. I really couldn’t say, although I wished I could.

This particular piece of hell, consisting of ice, stone and inadequate air to breathe, had begun that morning at a quarter past midnight. Our guide had woken us with the words: “It’s time; now is the hour.” We had gone to bed with our boots on, insulated against cold of minus 15 degrees. Wearing a woollen cap, scarf and headlight, I had tumbled out of the igloo tent, looking like a yeti. Cara’s words – “I’ve been dreading this moment” – had summed up my own feelings.

The route led up sheer cliffs that had been towering above us since the previous afternoon. This route had not been part of our initial planning. Our chief guide, Sammie, who had been studying our group of twenty-five over the previous four days, had recommended it and we had agreed, because by following this route – although fearfully steep – the group would be less liable to contract the dreaded altitude sickness.

Step by step, with Sammie in the lead and his assistant, Dixon, bringing up the rear, the train of headlights moved upward in the dark. After a mere twenty metres, Cara sank to her knees and vomited on the scree of the mountainside. I hastened to her side, but my heart sank into my boots. Either we turned round now or the opportunity was lost, and my eldest, with her fear of heights, would be forced to show her mettle. I pulled off my gloves and with gradually freezing fingertips I pushed an anti-nausea tablet down her throat and made her wash it down with a few sips of water. “My darling, today you’ll be facing the most difficult time by far of your short life. You’ll have to hang on,” I urged.

We moved to the back, where Dixon encouraged Cara in broken English, interspersed with Swahili. She didn’t say a word as we followed the vanishing climbers. Now it was only the Askari, my daughter and I making our way upward step by step over loose gravel and stones. Our words of encouragement were few and far between because, aside from the lack of oxygen, talking wasted energy. We were now more than 5 000 metres above sea level. We rested frequently, but only for short periods, or we ran the risk of freezing. When we stopped, Dixon held Cara in his arms, rubbed her back and crooned softly in her ear. The rubbing was alternated with gentle slapping to keep her awake. A lack of oxygen leads to drowsiness, followed by sleep, and ultimately death. My fatherly duties had been completely taken over by a stranger and I was bringing up the rear now. After patting her briefly on the shoulder, I had leaned on my walking stick and promptly fallen asleep, so that I’d had to force myself to wake up.

Time had lost all meaning. The need to keep climbing was predominant. Toes like ice cubes and numb hands made crawling on all fours nearly unbearable. In the light of the half-moon I was aware of vertical cliffs and yawning chasms on either side. Haltingly I warned Carla to look straight ahead and hold on for dear life. She might be the one who feared heights, but my fear for her safety struck terror in me. With my body I tried to shield her physically against the heights. She didn’t say a word; just kept moving steadily along.

After a gruelling seven hours the dawn began to break. We were climbing up the western slope of the mountain and we realised that the sun would not reach us before we got to the ice field at the top. Only when it became lighter did we really understand how dangerous the climb had been up till that point. We were perched on the cliff like swallows, so high that we could no longer make out the base camp below. I would certainly not have scaled those heights in daylight, especially not without equipment and ropes. It was nothing like the books, brochures and posters had said.

My road to Kilimanjaro had begun about 5 000 kilometres to the south a year before. One evening four of us on an eight-day hike through the Naukluft mountains had made a rash decision: “Let’s climb that koppie.”

Twenty-five souls were assembled and, with the dollar kicking the rand’s arse, an operator was contacted in Tanzania. We had all hiked before so we decided, of the two well-known routes up the mountain, we wanted to do the Machame route. The Marangu route, the so-called Coca-Cola route, sounded too easy and impersonal.

With this intention, we were dropped off by Air Tanzania at the Kilimanjaro International Airport between Moshi and Arusha.That was where we met Sammie, his four guides, two chefs and forty bearers. The next day, with a drizzle in the air, we tackled the mountain.

On the first day we trudged up the mountainside through thick sludge and rain forests, with colobus monkeys chattering in the tall jungle trees, watching the antics of their descendants. It was also the last time we were clean. A late start saw the stragglers stumbling into camp at nine o’clock that night after an 18-kilometre struggle.

The next day we ascended steeply to a height of 3 800 metres. We reached the Shira camp at around three o’clock in the afternoon. Rain forest had made way for a lava plateau, but also for ice-cold mountain winds. The bearers pitched our tents and immediately began to prepare food on open fires. Tanzanian Askaris put all other climbers to shame. Carrying loads of up to 40 kilograms, they stride effortlessly up the slopes.

It was here at Shira that Sammie proposed the alternative route up the western slope, starting from the Arrow glacier. His plan entailed two more days of gradual ascent and acclimatisation, then a steep climb to the brim of Kilimanjaro before ascending to the highest point. His reasoning was sound and our leadership element consented. Little did we know . . .

A morning’s hike through lava rock and alpine vegetation brought us to the foot of the Kibo massif. The altitude began to take its toll. Nausea, shortness of breath and headaches were the order of the day. The afternoon was passed taking in oxygen as we were too weak to do anything else. Sammie and his group tramped to and fro tirelessly, carrying water and wood, and even in those adverse conditions they served up a delicious supper of pasta, chicken and fresh vegetables. The cold drove us to our tents early.

We acclimatised until lunchtime the next day and, leaving the Lava Tower, we began an ascent of about 200 metres to the dilapidated hut at the foot of the Arrow glacier. The hut had been destroyed by a rock slide a few years before. It was there among the fallen boulders that Sammy had woken us that morning . . .

In single file we plodded along laboriously. The brink of Kibo was beckoning. Ice spilled over its side like icing sugar. As I pushed myself over the rim, the blinding sunlight on the snow made me reel. Dead tired, overwhelmed by dizziness and completely disoriented, I gasped for breath that wasn’t there. A sip from my water bottle produced only ice. Fear of snow blindness made me put on my cracked Second World War desert shades, but they fogged up immediately. This added to the unreal aspect of the plateau that we had just set foot on. Sammie pointed out an ice-covered “Karoo koppie” some distance away. “Uhuru – two hours.” The highest point in all of Africa, 200 metres higher than where I was standing now. Despondency got the better of a fellow climber. “I’m not going up there – I can’t go on. I’m on top of Kilimanjaro now – why would I want to climb to its highest point?” I shared his sentiments, but stumbled on in the direction of the koppie – in part, at least, to stop Cara from slipping and plunging over the precipice.

Were those drops of blood on the ice and snow in front of me? An automated shuffling gait: rest, shuffle, rest. Ice crunching, breath rasping, vision clouding. The only way was up. Sammie was standing in front of me, fists in the air. Uhuru – freedom! I grabbed my daughter . . . my voice croaked even more. I was on the roof of my continent. My friends arrived: stumbling, crawling, crying, but our joy was boundless. Embraces, congratulations, photos, laughter – we had made it!

I sat down on a chunk of ice, lit a cigar and sipped some Hanepoot from the distant Cape – one doesn’t die that easily after all.