Читать книгу To hell and gone - C. Johan Bakkes - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA different kind of Christmas

I was still opening my present (I happened to know it was a Bible), when kleinboet Christian toddled through the glass door on the stoep. In front of my eyes the window shattered and a shard fell from above like a guillotine, piercing his upper lip. He was only two years old and couldn’t understand all the blood and the screaming. It was the first Christmas Eve I can really remember. That evening in my eleventh year I dedicated my life to the Lord – please let Boetie live – as I carefully took the glass spear out of his palate and picked him up and handed him to Ma and Pa like an offering.

My mother, Margaret, believed that Christmas Eve was a Bakkes evening – as a family we would open our presents; we would be together. All her chicks under her wing. But she hadn’t taken into account what she had created, for it certainly wasn’t potatoes that she had planted and raised. Each of us, Marius, Christian, Matilde and I, had a yearning to seek out new horizons and to do things our own way . . .

On Christmas Eve 1982 I found myself in Oshakati, Sector One Zero, Vamboland. A few comrades and I had just liberated three chickens from a nearby village. The logistics men at the bulk supply shed had liberated a bottle or two of booze. Tonight we were going to celebrate Christmas – the troops in the observation towers of Alpha Company were on the lookout and would stop the enemy in their tracks . . .

On the fire the chickens became burnt offerings to Thor as we mounted the Buffels. For the soldiers at Oshivello, Christmas Eve had got off to a blazing start – 61 Mechanical Brigade was under fire and looking for support. It was no “Silent Night” for Swapo. I remember the wild look in my comrades’ eyes – what a Christmas gift it would be to survive . . .

We hung scraps of white paper from the thorns of the acacia that extended its branches like a crucifix over the Kwando flood plains. It would be our Christmas tree tonight. The quiet of the Western Caprivi settled in our hearts.

The elephant herd was unaware of our camp site.They were lumbering towards the river and heading straight for us. It was a large herd – about two hundred strong, the matriarch sniffing, her trunk raised like an antenna. I remember Pottie saying softly: “Don’t fuck with the king.” And then the wind turned and they were upon us and they were charging and trumpetting and we were shouting and beating on pots and lids and we knew if we ran now, it would be the end; and we stood our ground and they veered past. That evening my Christmas gift was a handshake, wrapped in friendship.

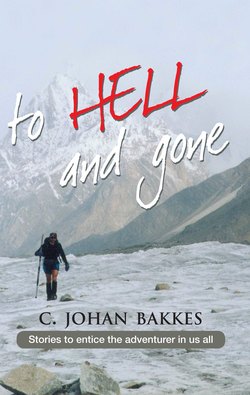

A white Christmas. It was bitterly cold – all year round in these parts. We were somewhere on the slopes of Numbur, a sacred mountain for the Sherpas of the Himalayas. We were lying in – actually we were snowed in. There was no escape. Certainly not tonight. Kalie and I lay snuggled up in the two-man tent that was buckling under the weight of the snow. When one hip gave in, we said “turn”, and we turned and faced the other side. “Boeta, do you realise it’s Christmas Eve?” I asked, and he pulled off his gloves and with chapped, frozen fingers and chattering teeth, he cooked barley on the primus – the most delicious Christmas dinner I had ever enjoyed.

“It’s going to be a dry Christmas,” I realised, as the captain in the Mauritanian army stopped our bus and pulled us over. I meant it literally as well as figuratively, for in the Islamic Republic of Mauritania alcohol is forbidden. We got out and the sifting Sahara sand filtered through our desert headdresses.

“Your cholera injection has lapsed,” said the man, as he looked through my papers. I knew he wanted a bribe, for inoculation against cholera was no longer mandatory. Surreptitiously I pressed a few wads into his hand. Not every person can buy his freedom on Christmas Eve . . .

And then? As life went on, and what used to be adventurous and different became tedious, and loved ones who had been away returned . . . you got the team together. “Tonight it’s going to be only us on Christmas Eve, the way my mother taught me.”

And Nanna roasted a leg of lamb and my son, Marc, built the fire and Cara, my daughter, sang. And one more time Mary explained to Joseph why they had to sleep in the stable tonight and men arrived with scented stuff and knick-knacks and even the farmhands left their sheep somewhere in the Ceres Bo-Karoo and Herod was out to kill. And you sat back contentedly and thought: What a different kind of Christmas!

And then Marc walked through the glass door.