Читать книгу No Magic Helicopter - Carol PhD Masheter - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Why Do Climbers Climb?

ОглавлениеJune 3, 2009. Bad weather had trapped us midway up the mountain for 11 days. Then a welcome break came between storms, and we had eagerly climbed the rugged ridge of rock, snow, and ice up to the highest camp. We needed one more good day to climb the last 3,000 vertical feet to the summit. Another storm of driving snow and high winds rolled in with a vengeance. Time had run out. It was time to descend and start a chain of plane flights home. Feeling sick with disappointment, I huddled in my tent and stuffed my down sleeping bag into its compression sack.

Tears filled my eyes and splashed onto my gloves, as I packed my gear. I felt silly about crying over a mountain, but hauling enough food, fuel, and equipment up the highest peak in North America had been very hard. If I wanted to summit Denali, I would need to return next year, after another season of hard training. I was not sure I had it in me. Then I remembered crying about another mountain for very different reasons. That mountain was Everest.

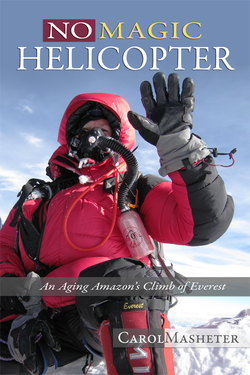

This is my story about the climb of my life. It describes what led me to try Mount Everest as an amateur woman mountaineer in my 60s, how I prepared, and what the climb was like for me. My account is subject to possible distortions of memory due to demands the climb made on me physically and emotionally. Others who were on Everest in the spring of 2008 may remember events differently.

Some climbers have written eloquently about their own Everest experience, the history of climbing Everest, the beauty of the Khumbu region where Everest is located, and the remarkable Sherpa people, without whose strength and skill most Westerners would have little chance of summiting the world’s highest mountain. I strongly recommend that readers read their books as well as mine.

I was an unlikely Everest climber. A woman in her early 60s, I was not very impressive looking -- five feet six inches tall and weighing about 135 lbs. I took medication for anxiety, depression, irritable bowel, and hypothyroidism. I was afraid of heights. Why would someone like me even consider climbing Everest, the highest mountain in the world?

There are probably as many reasons to climb Everest as there are climbers. My own climb was neither a lifelong dream nor a whim. My climb evolved from a life-long drive to do something outstanding and my fascination with big mountains. Perhaps I wanted to leave some record of my time on earth. Perhaps, as one Nobel Prize laureate put it, I was looking for love.

My earliest memory of wanting to do something outstanding was a childhood daydream while in the hospital. In the summer of 1953, when I was almost 7, my mother, younger sister, Linda, and I flew from our home in Southern California to Kansas for my grandfather’s funeral. My father stayed home, as he had limited vacation time from his job as an engineer. While we were in Kansas, my sister and I became ill. A local doctor in the small farm town of Pratt, near the even tinier town of Isabel where my grandmother lived, suspected we had polio and sent us on a tense midnight drive to Wichita for a formal diagnosis. There, I was terrified of the huge syringe used to perform the spinal tap. I fought like a wild cat, while a burly nurse tried to hold me still.

When the spinal tap confirmed that we both had polio, Linda and I were immediately sent to a polio isolation ward. It was hot and humid. The hospital had no air conditioning. We wore only cotton underpants and lay sweating on top of our sheets. The treatment for polio of the time seemed like torture. The intravenous horse serum made me vomit, until I was delirious. The steaming hot blankets blistered my skin, when nurses wrapped them around my naked arms, legs, and torso. Between torture sessions, nurses told me I was not allowed to sit up or get out of bed, or I would be paralyzed for life. Lying flat on my back 24/7, I daydreamed of doing something heroic when I got out of the hospital, like rescuing a drowning swimmer by the time I was 8 years old. Remembering my terrified thrashing in the deep end of the local pool earlier that summer, I made plans to become a better swimmer.

Finally doctors allowed me to leave my bed for the first time in weeks. Wearing heavy corrective shoes, I shuffled clumsily a few feet from my hospital bed and toppled into the arms of a nurse. I was weak, the arches in my feet were flat, and my back swayed alarmingly, but I could walk. I had escaped paralysis, as had my sister. At the time, I did not realize how fortunate I was. I was just really glad to get out of that cursed bed.

Back at home in Southern California, I did physical therapy every evening in the living room under my parents’ supervision. I picked up marbles with my toes, until my feet cramped. I squeezed a nickel between my buttocks, until my back ached. I did sit ups, until I could do no more. I had to wear heavy leather corrective shoes, while my friends wore sneakers and seemed to run like the wind.

My parents were afraid I would injure my weakened back, so they forbad me to lift the garage door to get my bike. When no one was looking, I would sneak outside and lift the heavy door like a giant barbell as many times as I could before grabbing my bike and peddling around the neighborhood. When my parents caught me, their disapproval hurt and their spankings stung, but I was determined not to be weak. If there were any silver linings to having polio, they were this early determination to be strong and the dream of doing something extraordinary. Why I reacted this way and did not accept a role of being “weak” or “sick” is still a mystery to me.

Polio, daily exercises, and corrective shoes were not the only things that set me apart. In the 1950s and 1960s rich girls went to finishing school to learn how to carry a suitcase, so their muscles would not show. I was more interested in riding horses and finishing first in school foot races. I wanted muscles, and I wanted them to show. Though I was more active than most kids my age and earned good grades in school, I was terribly shy. I had acne starting at age 9 and was painfully self-conscious about it. Selling Girl Scout cookies door to door, leaving fliers on people’s porches for my mother’s real estate business, and even answering the family telephone were agony. As a teenager, when my father dropped me off at the Methodist church for dances, I hid all evening in the bushes outside the social hall to avoid being asked to dance.

While other kids my age were going nuts over Elvis Presley, I fell in love with classical music. As a young teen, I dreamed of becoming a concert pianist and traveling the world to perform pieces by Mozart, Vivaldi, and Chopin, a curious dream for someone as shy as I was. After the launch of Sputnik, my school advisors noticed my aptitude for science and encouraged me in that direction. I liked science as well as music. On weekends after my piano lesson, I would ride my bike three miles to the local library and read “Scientific American.” I dreamed of making great scientific discoveries. I had no shortage of grand ideas, but I was not very talented in either music or science. My earnest diligence made me just good enough to fuel my ambitious dreams.

On some Saturdays, two other unconventional girls and I persuaded one of our parents to get up early and drive us to the Irvine Ranch, which in the early 1960s was still undeveloped land. We would spend the entire day hiking through hills of tall sun-cured grass and live oak, dodging herds of range cattle and avoiding clumps of prickly pear cactus, while keeping our eyes open for rattle snakes. I loved hiking up to a view point and gazing over the rolling hills. I felt confident and strong, away from the traffic, noise, and smog of where I lived, away from mean-spirited classmates who teased me about my acne.

Mary Tamara Utens, one of my hiking friends, showed me her older brother’s Eddie Bauer catalogs. In the 1960’s Eddie Bauer specialized in expedition down sleeping bags and clothing. I marveled at the pictures of mountaineers standing on snowy summits wearing puffy parkas, mountaineering boots, and crampons (metal spikes that mountaineers strap onto the soles of their boots to grip ice and hard snow). Climbing big mountains seemed really cool but completely out of reach for me. Surely only world-class mountaineers climbed such mountains, not awkward pimply teenage girls like me.