Читать книгу No Magic Helicopter - Carol PhD Masheter - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Phoenix From Ashes

ОглавлениеThe busy-ness of life pushed the Eddie Bauer pictures of mountains to the back of my mind for awhile. Becoming a scientist seemed like a more realistic career plan than becoming a concert pianist. In 1968 I graduated from UCLA in chemistry and accepted a job as a research chemist at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. I had never been further east than Arkansas, and though still painfully shy, I was eager to explore life as a newly launched adult. With my first paychecks I bought a Kelty external frame backpack and a down sleeping bag. At the apartment I shared with two other young women, I tested the sleeping bag in my unheated attic bedroom. After shivering inside the bag for the first 15 minutes to warm it up, it never failed me, even when temperatures dipped below zero degrees Fahrenheit. Emboldened, I did several backpack trips with the Sierra Club. I loved backpacking in wilderness and climbing peaks in the Sierras and the Rockies. As much as I enjoyed living in central Connecticut with its pretty patchwork of fields, forests, towns, and cities, I lived for those annual backpack trips in the rugged mountains of the West.

I tried climbing even higher mountains. In 1972, I went to East Africa and climbed high on Mt. Kenya. Unlike the triumphant joy I had felt on previous summits in the Rockies and Sierras, on Point Lenana at 16,355 feet elevation, I experienced tunnel vision, lassitude, and a terrible headache. Later I learned these are the classic symptoms of moderate altitude sickness, probably exacerbated by dehydration due to a nasty case of travelers’ diarrhea. Happily, I was able to descend from Point Lenana under my own power. A week later I climbed 3,000 feet higher to the crater rim of Mt. Kilimanjaro by the Marangu Route. Though I did not experience symptoms as intense as those on Point Lenana, I still felt dull, sick, and tired. I was glad to have tried both mountains, but the climbs were cold and joyless.

Hiking up big mountains was only one of my youthful explorations. I pushed myself to overcome my shyness and dated. I fell in love with a guy who did not feel the same way about me. I learned to scuba dive, so I could dive with my next boyfriend. He also was less involved with me than I was with him, a pattern that I would repeat several times with other men. Perhaps I felt more in control as the pursuer than the pursued. Between failed relationships, I drove my VW beetle up the then unpaved Alcan Highway and explored parts of Alaska. I raised and trained Morgan horses. I trained for and ran the Boston Marathon as a qualified runner. Some of these experiences were fun and rewarding. Others were painful. They all helped me figure out who I was and what I wanted out of life.

After a dozen years of working at universities as a research chemist, I decided to change careers. Though I loved research, I was not setting the world on fire as a scientist and wanted to get into something more people related. My childhood fantasy of saving a drowning swimmer had evolved into wanting to be some kind of healer or teacher. I wanted to help people more directly than working in a lab. In the 1980s I earned a masters degree in marriage and family therapy then a doctorate from the University of Connecticut in Storrs. In 1988 I accepted a tenure track position at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. The department that hired me was forced to merge with another department and expected me to publish in nutritional sciences instead of the area of my graduate work. I knew I needed to find a better professional fit.

Two years later I accepted another tenure track position at the University of Utah in Salt Lake. I settled into the life of an assistant professor, teaching classes, doing research, and applying for research grants. I had moved to Salt Lake to work, but I soon discovered the nearby mountains. I joined the Wasatch Mountain Club, a local outdoor club, and hiked with other members on the weekends. I met a guy who liked nerdy outdoorsy women like me. He taught me to rock climb and backcountry ski. We enjoyed talking about science and seemed to “get” each other. We became a couple.

My career bloomed. I published sole-author papers in the top peer-review publications in my field. Several times I was a finalist for my college’s superior teaching award. I seemed to be on my way to doing something extraordinary, building a legacy as an innovative researcher and a respected teacher. At last, in my 40s, I seemed to have found my life’s work and my life partner. Better late than never.

In 1995 a university colleague and fellow Wasatch Mountain Club member, Bill Thompson, summited Cho Oyu, whose name means Turquoise Goddess in Tibetan. The sixth highest peak in the world, Cho Oyu is in the Himalayas near Everest on the border between Tibet and Nepal. The Eddie Bauer pictures of climbers on big mountains resurfaced in my fantasies and rekindled my imagination. I thought real people like Bill can do this! Maybe I can too.

I took Bill to dinner and asked him how to prepare for such a climb. Bill’s advice was clear and to the point. “No reputable company will guide you up a peak like Cho Oyu without experience at high altitude and the right set of skills. Build a mountaineering resume. Climb with a respected guide service, like American Alpine Institute [a climbing school and mountain guide company based in Bellingham, Washington.] You can get a lot climbing experience in South America.” I thought perhaps after I had tenure, I could go to South America for a three week vacation and climb.

Starting in 1997, I experienced several major losses within 18 months. I lost a hard struggle for tenure. My department claimed I was not publishing enough. When I had asked how many publications would be enough, they would not tell me. Then I learned my boyfriend of six years was involved with someone else. Hurt and angry, I ended our relationship. My sister became seriously ill in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where she lived. My mother died suddenly in Southern California. I felt devastated – again and again. I felt as though I was being attacked by wild beasts, ripped open, and left to bleed to death.

I did not know who I was or where I was going. A failed professor at age 50, I became a student again. I took university courses in computer science, calculus, and physics, sometimes along side my former students. “What are you doing here, Dr. Masheter?” some asked. “Learning something new, like you,” I would shrug and reply. I avoided the topic of being denied tenure, because talking about it brought back an overwhelming sense of anger and shame. I worked several low-paying part-time jobs as a computer instructor and programmer to reduce the drain on my savings. Perhaps I needed to prove I was a smart worthwhile person. Perhaps I was punishing myself for failing as a professor and as a relationship partner, for not seeing my elderly mother and my only sister more often.

Stress piled up from grief, anger, overwork, and anxiety about my professional and financial future. Some nights I awoke screaming in pain, my legs locked rigid by muscle cramps. My innards felt as though invisible hands were twisting my intestines into those silly balloon figures for kids. I lost 15 lbs. and felt weak and tired.

The weight loss concerned me enough to see a doctor. He reassured me that I did not have cancer, an ulcer, or some other horrible disease. He referred me to a nutritionist and a gastrointestinal specialist. Both concluded I had severe irritable bowel syndrome. The nutritionist recommended smaller more frequent meals, eating yogurt with live cultures, and avoiding wheat. The GI specialist recommended I eat more wheat bran, contradicting the nutritionist’s advice. Go figure, I grumbled to myself.

I experimented with the specialists’ contradictory suggestions. Those that made me feel worse I stopped. Those that eased painful symptoms I continued. The leg cramps turned out to be symptoms of hypothyroidism. The cramps became less frequent and less severe, after I started taking thyroid medication. Estrogen and progesterone were prescribed to reduce my hot flashes and help me sleep better. They did not improve my sleep and made my intestinal symptoms worse, so I quit taking them. Gradually I began to feel better.

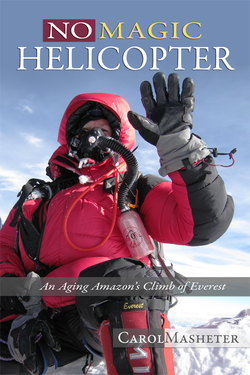

Slowly, some things became clear. I wanted to stay in Salt Lake. It felt like home. Hiking, climbing, and backcountry skiing with friends in the nearby Wasatch Mountains was a big part of my life. Perhaps now would be a good time to try climbing in the Andes. Taking a foreign trip when my financial future was so unsettled seemed counter intuitive. However, I saw this trip as a “vacation” from the anger, sadness, and stress I was experiencing. Instead of the happy celebration I had imagined after getting tenure, my start in high-altitude mountaineering was born from loss and pain. I rose like a phoenix rising from ashes.