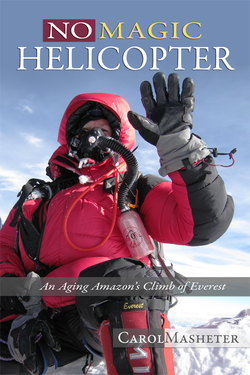

Читать книгу No Magic Helicopter - Carol PhD Masheter - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Crampon-eating Crevasse

ОглавлениеAt age 61, I was a capable, though anxious, intermediate rock climber and ice climber. I had developed strategies for dealing with my fear of heights, but it was still a serious demon. I had summited a dozen peaks over 17,000 feet elevation, plus three peaks over 20,000 feet elevation. Yet I was not sure I had all the skills needed to climb Everest. I emailed Adventure Consultants and asked what I could do to further prepare myself. They suggested I take their Everest Preparation Course in New Zealand. As much as I would have liked to visit New Zealand, I could not take that much time off from work. The only company Adventure Consultants trusted to prepare me for Everest, other than themselves, was American Alpine Institute, my old friends with whom I had enjoyed several climbs in the Andes.

I arranged for training in the Mt. Baker icefall in the Cascades in July 2007. It rained the whole time Alasdair Turner, an American Alpine Institute guide, and I practiced in the icefall, a crazy maze of giant blocks of ice, crevasses (cracks in the ice), and seracs (ice towers). While trying to climb the wet rain-polished ice, I took several hard falls. Three years previously I had broken four ribs while backcountry skiing, then a year later I broke an ankle while running. Discouragement and negative self talk threatened to overwhelm me. You’re too old to be falling like this. You could break something – again. This is too difficult and too risky. I was tempted to quit. However, I am not a quitter. Each time I fell, I scrambled back onto my feet and tried again, trying to act more confident and enthusiastic than I felt. When I climbed to Alasdair’s satisfaction, we moved on to something more difficult.

On our last morning Alasdair and I went for one more climb, an informal final exam. As the sun rose in the sky between rain showers, we climbed high into the icefall, moving well. My confidence soared. I was getting the hang of this. Near the top of the icefall, Alasdair told me to traverse up and around the corner of a steeply angled giant block of ice. I got both crampons into the smooth ice and raised my ice axe like a hammer to drive its pick into the face around the corner.

Suddenly my feet popped loose. I fell backwards and whacked the base of my skull just below my climbing helmet on a shelf of ice behind me. Pain exploded inside my head. I saw stars. As I bounced hard and continued to fall, I watched helplessly as my right crampon broke and slipped down a crevasse faster than a greased snake. I crashed onto my lower back and slid toward the crevasse that just ate my crampon. Alasdair’s belay (use of friction on a climbing rope connecting him to me) jerked me to a stop. I leaned forward and peered between my bent knees into the crevasse’s dark depths. I could not see the bottom. My heart ricocheted against my ribs like a panicked animal trying to escape from a cage. My inner whiner wailed, now what? How am I going to get out of this mess with only one crampon?

I took several deep breaths. Break the problem into smaller steps, I coached myself. First I needed to stand up. Pain shot through my head and back, as I sat up and tried to get my weight over my lone crampon. The wet smooth ice was very slick, so standing took several tries. Finally I rose unsteadily like a newborn foal on wobbly legs.

My crampon-less boot slipped out from under me every time I tried to take a step. I used my ice axe to chop steps, tiny ledges actually, to anchor the edge of my boot’s sole. I thought of the early mountaineers who did this routinely and gained a deeper respect for what they accomplished before modern mountaineering boots and crampons. Slowly Alasdair and I picked our way through a maze of weirdly angled ice blocks and crevasses. Alasdair led, placing ice screws and clipping the rope between us as protection in case we fell. I followed, removing ice screws and slings as I climbed past them.

Finally, we reached lower-angle ice peppered with embedded gravel, which provided some traction for my crampon-less boot. My shoulders, tense with anxiety, relaxed a little. Even with the bruises and heart-pounding fright from the crampon-eating crevasse episode, I felt good about the icefall training. I had overcome self-doubt and improved my ice climbing skills. I had gotten into a desperate situation, calmed myself, and gotten out of it safely. I was ready for the next step.