Читать книгу No Magic Helicopter - Carol PhD Masheter - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

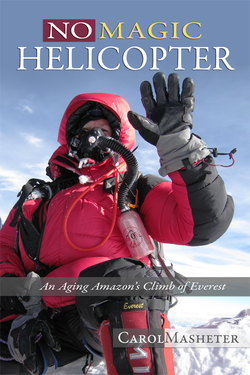

Turquoise Goddess

ОглавлениеAt 50 years of age, I signed up for climbing instruction and mountaineering in the Bolivian Andes with the American Alpine Institute. There I became the student of Brian Cox, a guide half my age. Brian did an excellent job of teaching mountaineering skills. He instructed four guys and me in crampon techniques, how to climb as members of a rope team, safe route finding on glaciers, ice climbing with two ice tools, and mixed climbing on rock, snow, and ice. Brian stressed the importance of adequate hydration and caloric intake, gradual acclimatization, and pacing. He was patient and positive.

Brian’s instruction contrasted sharply with my experience on Mt. Kenya and Mt. Kilimanjaro. Since the early 70s, knowledge about reducing the risk of altitude sickness had improved. Thanks to Brian’s gradual acclimatization program and insistence that we drink plenty of water, I had no problems with altitude sickness in Bolivia and climbed four peaks ranging in elevation from 17,000 to 21,000 feet.

Climbing in the Andes pushed my abilities and taught me a lot. Of course, I doubted my sanity during the miserable moments, like when four of us climbed to 21,000 feet elevation in a driving snow storm. However, the moments of doubt and misery paled compared to the joy of summiting high, icy peaks with melodious names like Eslovania, Piramide Blanca, Ilusion, and Illimani. I had such a wonderful time, I returned to climb in South America and summited additional peaks: Piqueno Alpamayo, Huayna Potosi, Janko Uyu, Culim Thojo, Illiniza Norte, Cayambe, Cotopaxi, and Chimborazo. Climbing to the top of big mountains on my first attempt began to feel routine, the logical outcome of getting very fit, buying the right gear, learning appropriate skills, drinking only treated water, eating only properly prepared food, and taking enough time to acclimatize properly.

I had so much fun climbing in South America, the dream of climbing Cho Oyu faded for awhile. However as I approached my 60th birthday, several guides encouraged me to try the Turquoise Goddess. I was strong and fit for a woman of my age, but each year I lost a little speed and power. I got injured more easily and took longer to recover. Somewhere I read inactive people lose 3% of their strength every year, while active people lose only 0.5% a year. Apparently we can slow the aging process, but we cannot stop it.

If I wanted to try Cho Oyu, I needed to do it soon, or I would be too weak. I had recently started a new career in public health, and my vacation time was very limited. I would need permission to take an unpaid leave of six weeks from my new job with the Utah Department of Health to climb Cho Oyu.

In the spring of 2005, I dropped hints. My boss, Wu Xu, was a bright volatile Chinese woman, who came of age during the Cultural Revolution. Not allowed to go to high school, she and her friends read banned books and secretly educated themselves at considerable risk. I admired her fierce determination to learn. I hoped she could relate to my climb of Cho Oyu. When I asked her for permission to take unpaid leave, Wu exploded, “Why you want do that?! Too dangerous! You die up there!” Her reaction surprised me. For a moment, I froze, not knowing how to respond. Then I heard myself say quietly, “Wu, people die right here in car wrecks every day.” Wu walked away, shaking her head in disbelief that I wanted to do such a crazy thing.

Now what? I wondered. Do I quit my job to climb a mountain? My chances of finding another job I liked as well as this one at nearly 60 years of age did not seem good. Climbing big mountains in distant countries was an expensive hobby. I could not afford to retire and climb fulltime. The next morning I was settling into my work, when Wu approached me tentatively. “If climbing this mountain is your dream, I support you anyway I can,” she said quietly. The change was so unexpected, I was numb with surprise. “OK,” I grinned. I walked on air for days.

My next step was choosing an expedition. I was going to climb a mountain nearly 27,000 feet in elevation on the other side of the world. I wanted to optimize my chances for a safe summit and return. I wanted the best leadership and resources I could afford. American Alpine Institute, the company with which I had had so many enjoyable climbs in South America, was affiliated with Adventure Consultants. Based in New Zealand, Adventure Consultants runs deeply resourced expeditions with top-notch guides. They are expensive, but they have had a good safety record for guiding amateur climbers up some of the world’s highest peaks, including Cho Oyu and Everest.

With some trepidation I sent my application and climbing resume to Adventure Consultants. At the time the oldest client they had guided on Cho Oyu was 53 years of age. I was nearly 59. To my surprise and delight, they accepted me. After I had met and talked with a younger Salt Lake man who had summited Cho Oyu without supplemental oxygen, I wanted to “climb pure” like him. Because I seemed to have solved my altitude problems in the Andes, I expected no problems climbing almost 6,000 vertical feet higher to the summit of Cho Oyu. I trained hard. By the departure date in late August, I felt ready and confident.

My Cho Oyu experience could fill another book. However, this book is about Everest, so it includes only the highlights of lessons learned on other mountains. Climbing in the Andes made me confident, even cocky. Cho Oyu cut me down to size. At Advanced Base Camp at 18,300 feet elevation, I slept poorly and felt lousy much of the time. Eating higher on the mountain was nearly impossible, a problem I had not experienced previously. I went from being the strongest climber on some of my South American climbs to the weakest of our team to summit Cho Oyu. When I staggered the last few steps to the top, I was so happy I wanted to jump over the moon, but all I could do was kneel in the snow and gasp for air. My usual triumphant summit howl, “aaahhhooo… (cough, hack, cough, cough),” sounded like a dying animal. I stared dully at the summit of Everest, another 2,100 vertical feet higher and about 13 miles east as the crow flies. My team mates chattered excitedly about trying Everest next. That day I could not imagine climbing a single foot higher.

Cho Oyu is a popular practice peak for climbers who want to try Everest. After I returned home, friends asked me whether I wanted to climb Everest. I said no and meant it. Each step to the summit of Cho Oyu had been a sheer act of will.

I could think of many reasons not to climb Everest besides my own physical limitations. I had read that Everest attracted too many people with big egos, too much money, and not enough high altitude mountaineering experience. It also attracted people trying to climb “on the cheap.” With few resources they had little chance of summiting and were at high risk of getting into serious trouble and putting others at increased risk. Accounts of the deaths and injuries in Jon Krakauer’s “Into Thin Air” terrified me. Everest seemed too crowded, too risky, too expensive, and beyond my abilities. I was so happy to have summited Cho Oyu. I considered it to be my “swan song” for climbing big mountains. I sold my new down suit and down sleeping bag, rated to minus 40 degrees, on eBay, figuring I would not need them again.

The following year, I learned that Ana Boscarioli, my tent mate on Cho Oyu, summited Everest, becoming the first Brazilian woman to do so. Thoughts about big crowds, high price tags, death, and injury evaporated. If she can do it, maybe I can too, chirped my inner optimist. Then my voice of reason argued, Ana is 20 years younger than you. On most days above 20,000 feet elevation she was stronger than you. Get real.

Even with these doubts, I could not stop thinking about Everest. Some experts claim the body remembers altitude. Perhaps if I climbed high again, my body would adapt better. Maybe I could find foods I could eat and keep down. Maybe I could find ways to sleep better. If I could solve these problems, I would have a reasonable chance on Everest.