Читать книгу Forgotten Voices - Carolyn Wakeman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

Gathering a Church

By the time a town meeting in 1693 established a church and called its serving minister to office, Moses Noyes had preached in Lyme for almost three decades.

At a town meeting it was desired and agreed upon with the inhabitants of this town, as agreed by a unanimous vote, that there may be a church gathered in this town and Mr. Noyes called to office if it may be obtained according to rules of Christ.

No one knows why it took twenty-seven years to establish a church in Lyme. So unusual was the long interval between the minister’s arrival and his call to office that his successors offered wide-ranging explanations. Rev. William B. Cary (1841–1923) speculated in 1876 that the difficulty of dealing with “wild and jealous tribes of Indians” caused the delay. Rev. Arthur B. Shirley (1902–1968) argued in 1893 that the shrinking of Saybrook’s congregation after its minister left for Norwich in 1659 brought objection to a separate church in Lyme. He assumed that Mr. Noyes had spent the intervening years “directing the labors of the negro slaves upon his farms and performing such ministerial labors as the situation allow[ed].”

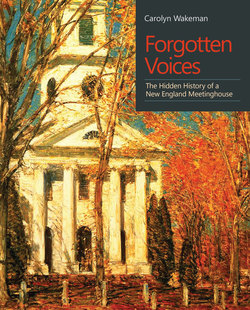

When local writer Kendall Banning photographed Old Lyme’s historic sites in the 1930s, he titled his view of Meetinghouse Hill The Road to Eden.

Other Connecticut towns installed ministers with far less delay, thereby authorizing them not only to preach the Gospel but also to administer the sacraments and admit as church members those who “owned the covenant” and offered a public profession of faith. In New London, Simon Bradstreet (1640–1683/4), a Harvard schoolmate of James and Moses Noyes, started preaching in 1666 and four years later was “formally inducted into the pastoral office by ordination.” In Stonington, James Noyes began preaching in 1664 and was called to office when the town organized a church ten years later. Lyme’s inhabitants initially approved a similar interval.

Not quite ten years after the minister’s arrival, a town meeting in 1675/6 voted unanimously that “there may be a church gathered which may be for the glory of God and edification of each other according to the laws of the Commonwealth.” The report of the meeting entered in the town book explained that Lyme was in “want of being in a church way” and remained “without the administration of all the ordinances of Christ,” even though “from the first settlement, which is now ten or eleven years,” it had been “under the ministry of the word.” When the town did not implement the decision, the sacraments remained unavailable in Lyme. Records of Saybrook’s church do not survive, but its historian surmised that Lyme inhabitants were “subjected to the necessity of crossing the river for participation in the ordinances of baptism and the Lord’s Supper.” New London’s church records show that Rev. Simon Bradstreet baptized several inhabitants of Lyme. Among them were the children of John Borden (1635–1684), baptized in 1670, not long after a Lyme town meeting approved “a sufficient highway to Borden’s house.”

A Sunday afternoon tradition for Charles Ludington’s family began with a stroll among the gravestones in Duck River Cemetery followed by a walk to scenic Meetinghouse Hill.

Lyme’s deputies, in an effort to implement the town meeting decision, appealed to the General Court in 1678 “in behalf of Mr. Noyes and other Christian people” for “liberty to organize into a church society.” The Court “countenance[d] them in their regular proceedings” and offered “encouragement in so good a work,” requiring only that they “take the approbation of neighbor churches therein and attend the laws of this colony.” As the decision languished, Mr. Noyes continued preaching, participated actively in town affairs, and supplemented his landholdings. He also decided to marry.

Ruth Pickett Noyes (1653–1690) grew up in a New London family of means and perhaps some notoriety. She was fourteen when her father, John Pickett (1629–1667), died on a return voyage from Barbados, leaving a substantial estate. Her mother soon remarried, and her stepfather Charles Hill (1629–1684), also a New London merchant, went “to and from Barbados.” Ruth was seventeen when Simon Bradstreet baptized “Mr. Pickett’s children, John, Mary, Ruth, Mercy, William,” together with “Mr. Hill’s child Jane” and “Widow Bradley’s daughter Lucretia.” A year later, in 1672, a “negro servant of Charles Hill” appeared before the county court “for shooting at and wounding a child of Charles Haynes.” The General Court in Hartford in 1675 ordered Charles Hill to pay damages of £35 for a wound inflicted “by the accidental discharge of a gun in the hands of Mr. Hill’s negro servant.” The ruling noted that “the negro belonged to the estate of Mr. John Pickett, deceased.”

Ruth was twenty-two when her mother’s widowed sister Elizabeth Brewster Bradley (1637–1708) appeared in court in New London in 1673 for “a second offense in having a child out of wedlock, the father of both being Christopher Christophers, a married man.” The court sentenced Widow Bradley “to pay the usual fine of £5, and also to wear on her cap a paper whereon her offence [was] written, as a warning to others, or else to pay £15.” Christophers (1631–1687), the child’s father, owned wharves and warehouses in New London jointly with Ruth’s stepfather Charles Hill.

No record of Ruth Pickett’s marriage to Moses Noyes has been found, but she likely did not move to Lyme until after the minister’s six-month enlistment in 1675 in King Philip’s War, for which he received as compensation a parcel of land in the town called Voluntown. A list of English volunteers indicates that his brother James and his cousin Nicholas both served as chaplains, but Moses Noyes’s role in the bloody campaigns that cleared native inhabitants from large areas of New England is not specified. Whether he had already built a dwelling on his home lot not far from the sawmill in 1678 when the birth of his first child, Moses Noyes Jr. (1678–1743), was entered in town records is not known. The “three scores of upland lying by mile brook” laid out for Moses Noyes was not recorded until 1688, a decade after his son’s birth, but the parcel may have been allotted to the minister twenty years earlier in the first division of town land.

Curious about the dwelling of Lyme’s first minister, local artist Ellen Noyes Chadwick relied on her father’s recollection to create a pencil sketch of Rev. Moses Noyes’s parsonage.

While Mr. Noyes waited to be called to office, the town appointed representatives each year to collect his rate. Not everyone fulfilled that obligation, and collecting the minister’s salary became such an urgent concern in 1679 that a town meeting pledged to “gather all the arrears which are due to Mr. Noyes from the time of his first coming among us” and also threatened to restrain any who refused to comply. A subsequent meeting in 1683/4 pledged “to use all lawful means to gather in the arrears of the rates due to Mr. Noyes for all the years past forthwith.” The town further stiffened the power of its rate collectors in 1685 by giving them “as full power to get and gather the rate and all arrears of such rate to Mr. Noyes as the constable has to gather the country rate.”

Moses Noyes was almost fifty when a town meeting determined in 1693 that a church was “desired and agreed upon with the inhabitants.” A unanimous vote then decided again that “there may be a church gathered in this town.” This time the decision specified that “Mr. Noyes [be] called to office if it may be obtained according to rules of Christ.” Whether neighboring clergymen gathered for an installation procedure is not known, but town records thereafter referred to the long-serving minister as “Reverend Noyes.” A year later the General Court invited the “Reverend Mr. Moses Noyes” to deliver a sermon in Hartford to accompany the annual election of representatives.

A simple gravestone in Duck River Cemetery marks the burial place of Ruth Pickett Noyes, the first minister’s wife, who died at age thirty-six.

Ruth Noyes did not live to see her husband called to office. Her death in 1690 at age thirty-seven left Lyme’s minister with four children ranging in age from three to thirteen. Moses Noyes did not remarry, and the care of his children along with the work of his household likely fell to Arabella, an enslaved black woman whom he later bequeathed to his younger daughter Sarah. Three years after the death of the minister’s wife, Rev. James Noyes informed Judge Samuel Sewall (1652–1730), a mutual friend in Boston, “I heard but now that my brother Moses is well & his family.”