Читать книгу Forgotten Voices - Carolyn Wakeman - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

New Light on Old Stories

For last year’s words belong to last year’s languageAnd next year’s words await another voice.

T. S. Eliot, Little Gidding

Lost segments of New England’s past await discovery in the scattered records of its meetinghouses. The first public buildings in early colonial settlements witnessed Sabbath lessons and prayers, town meetings and court hearings, militia drills and punishments. Today documents tucked away in libraries, archives, and attics help piece together the events, controversies, and personalities that shaped developing towns and their churches. Forgotten voices survive in sermons, in town and parish records, in wills, deeds, and court testimonies, in newspapers, diaries, and family letters. They speak of scripture and salvation, liberty and taxes, controversy and scandal, patriotism and privilege, enslavement and exclusion. Despite the passage of time, these primary accounts of religious duty, moral behavior, and civic responsibility retain a startling familiarity.

This book tells the story of four consecutive meetinghouses, no longer standing, that defined the religious and secular life of a prominent Connecticut town over 250 years. Established by the colony’s General Court in 1665/6, the town called Lyme (later Old Lyme), initially covered more than eighty square miles of forest, meadow, and salt marsh at the mouth of the Connecticut River. By then local Pequots had been pushed east, then massacred when Captain John Mason in 1637 led a colonial force that torched their village near the Mystic River, incinerating elders, women, and children.

Three decades later settler colonists had negotiated with Mohegan chief Uncas for lands stretching north along the Connecticut River and east along Long Island Sound and chose a hilltop location for their first public gathering place. Until a fire caused by a lightning strike destroyed the third meetinghouse on that site, Lyme’s colonial inhabitants prayed, sang, argued, voted, judged, and disciplined in a combined church, community hall, and justice court. A stately fourth meetinghouse with pillared façade and soaring spire, built in 1817 a mile west at the junction of the town’s two “highways,” excluded secular gatherings. Funded by prospering parishioners with increasingly cultivated tastes, the new edifice was designed as a house of God.

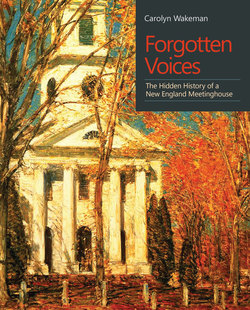

As tourism developed after the Civil War and a railroad bridge across the Connecticut River improved access to the coastal town, metropolitan artists discovered the beauty of Old Lyme’s landscape and the charm of its historic homes. At a time of growing industrialization and immigration, the scenic town became a summer destination and an art colony. Childe Hassam, regarded as the dean of American impressionism, captured the rural meetinghouse, described as “a perfect piece of colonial architecture” and the “ideal New England church,” bathed in autumn light and color in 1905. “Nothing more American on all the continent,” sculptor Lorado Taft remarked about Hassam’s Church at Old Lyme.

Over the centuries, what transpired within the town’s meetinghouse walls slipped from view. To explore a forgotten past, I searched for voices that reached across the decades to reveal what people thought, why they acted, and how they responded to changing circumstances, values, and opportunities. My search began when Lyme’s first church, now the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme, celebrated its 350-year history in 2015. Existing accounts left me uncertain about church beginnings, curious about what had unfolded inside early meetinghouses, and intrigued by the role of public memory in the prevailing narrative. Booklets and family memoirs offered summary information and flattering anecdotes about acclaimed ministers and prominent residents. More probing local histories added documentation and depth, but gaps waited to be filled, emphases reconsidered, and assumptions challenged. To shed new light on old stories, I searched for details, connections, and contexts.

Forgotten Voices gathers short passages from period texts to reexamine, expand, and personalize the local past. Whether a memorial to the colonial legislature about Christianizing Indian families, a Revolutionary-era sermon posing the alternatives of independence or slavery, a faded notebook detailing the formation of a Female Reading Society, or a brief notation about erasing church records to obscure anti-abolition views, the selected passages convey decisions and beliefs that resonate beyond the confines of one Connecticut town. Ties of marriage, commerce, education, and faith connected local families to New England’s centers of influence and power, to the cotton-rich South and the developing West, to New York and Barbados, London and Canton. Words that echo from Lyme’s pulpits, pews, parlors, and taverns detail events that shaped a particular community but also sketch the regional contours of the evolving American experience.

Accompanying images make distant lives and times visible. The mark of an enslaved woman consenting to her deed of sale, a hand-drawn map of the town’s parishes, a wooden box that transported tea from Canton, the pocket Bible carried by a Civil War recruit, a nostalgic cover illustration for the Ladies’ Home Journal, all pull a forgotten past into present focus. The surviving documents, objects, photographs, and paintings also prompt reflection on what remnants and representations of the past survive and what is missing from the visual record.

Silences spoke loudly as I searched for meetinghouse voices. Ministers, judges, and merchants, the dominant landowners whose public influence defined the town’s religious and secular affairs, spoke clearly and authoritatively in sermons, church records, town meeting reports, and court decisions. Women’s reflections, while publicly muted, filled family letters and lingered in journals, albums, and scrapbooks. The voices of those marginalized and enslaved echoed faintly from birth records, baptismal lists, property transactions, runaway notices, and grave markers in the town where three branches of my family had settled in the 1660s.

I remembered a fourth-grade class trip to Meetinghouse Hill, where no trace of the town’s first gathering place remained and a country club offered scenic views of the Connecticut River. We children peered through the underbrush at a mile marker left by Benjamin Franklin’s postal route surveyors measuring the distance to New London. We examined lichen-crusted inscriptions on crumbling gravestones in an early cemetery. We learned that the hilltop location had provided protection from Indian attack. We did not learn about the systematic elimination of Native American presence or that the town’s ministers and prominent families owned enslaved servants for a century and a half. We had no idea that in the third meetinghouse on that site, seats for “the black people” in the corners of the rear gallery had been raised only in 1814 so they “could see the minister.” Even today, when scholars articulate the consequences of settler colonialism and document the persistence of chattel slavery in Connecticut, it’s local impact has largely disappeared from public memory.

As my search for the meetinghouse past brought startling discoveries about privilege and power, about the intersection of private lives and public actions, about habits of memory and forgetting, its history continued to evolve. When a Pakistani couple in New Britain, the taxpaying owners of a successful pizza restaurant, received notice of impending deportation for an alleged visa violation, the town’s fifth meetinghouse became literally a sanctuary. Church members in 2018 invited Sahida Altaf and Malik bin Rehman to set up housekeeping in a former Sunday school classroom. Their five-year-old daughter Roniya, an American citizen, joined them on weekends while the immigration appeals process worked its way through the courts. For seven months, until the deportation order was temporarily lifted, the threatened South Asian immigrant family remained sequestered. An ankle bracelet assured that Malik would not step outside. When award-winning author and journalist Dave Eggers reported the story in the New Yorker in August 2018, national attention focused again on Old Lyme’s meetinghouse, where new voices spoke from inside its walls.

Author’s Note

The sections that follow focus closely on local events and personalities between 1664 and 1910, and detailed endnotes provide historical and scholarly context. To make distant voices more accessible, I modernize spelling, capitalization, and punctuation in early texts. As a reminder of the calendar change in 1752, when Britain and its colonies adopted the Gregorian calendar that shifted the start of the new year from March 25 to January 1, I retain the use of a slash for dates between those months. Because early births and deaths were inconsistently recorded, life dates provided are sometimes approximate. Also, I refer to the town as Lyme until 1857, when the original first parish became the separate town of Old Lyme. Portions of this book appeared earlier in articles posted online for the Florence Griswold Museum’s history blog From the Archives.

Forgotten Voices is being published at a time when churches, communities, colleges, and families are recovering long-buried histories, probing past actions, engaging in truth and reconciliation projects, and acknowledging their roles in slavery and the subjugation of Indigenous peoples. My own reconstruction of the history of a Connecticut meetinghouse reflects that wider effort. This book recovering lost segments of the New England past may serve as a resource for others who seek to cast new light on old stories.