Читать книгу Forgotten Voices - Carolyn Wakeman - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER NINE

A Dark House

After Rev. Moses Noyes died in November 1729, Saybrook’s minister delivered a eulogy in Lyme’s meetinghouse. He offered not only praise for a learned teacher and valued friend but also warnings that ongoing controversy in the parish could erupt into open strife.

I must now offer a word to this Church & Society, you have lost an excellent and eminent pastor, What shall I say?… His doctrine once distilled as the dew and the rain, but now you will see him and hear him no more. This bereaved flock surely mourns, his study mourns, his very books mourn, as it were, leaving none so able to look into them; his family mourns, his pulpit mourns, this is a dark house and desk now. You must allow me to share with you in tears.

When Rev. Azariah Mather delivered a sermon “occasioned by the decease of the Reverend Mr. Moses Noyes,” he offered words of consolation from the pulpit to the “bereaved flock” in Lyme’s meetinghouse. The “eminent pastor” who had served the town for sixty-three years would be heard no more. “This is a dark house and desk now,” Saybrook’s minister, age forty-three, lamented. He had viewed Moses Noyes as both a mentor and a father, he wrote in his Discourse Concerning the Death of the Righteous, and his remarks reflected his personal experience.

The printed version of the funeral sermon in 1731 opened with Mather’s note of condolence to Moses Noyes Jr.: “Sir, At the instance of many & your solicitation in particular, I have adventured to let come forth to the light some things, delivered upon the death of your deceased & excellent parent.” While the Discourse offered lofty praise for the elder Noyes’s character, learning, and godliness, it also warned that “sparks of contention” in the parish were “ready to break out into a flame.”

To preserve Rev. Moses Noyes’s gravestone, church members removed it from Duck River Cemetery in 2007 and substituted a replica. Today a glass case in the church fellowship hall protects the original monument.

The choice of a successor loomed over the “dark house” when Mather brought the sparks of contention into the light. Concerned with discord among church members, he made no reference to the dissenting beliefs of Baptists, which two years earlier had filled Noyes with “a pious Zeal to withstand the designed propagation of their Errors.” More pressing was the loss of the minister’s doctrine that “once distilled as the dew and the rain.” While some had “censured” Noyes for being “backward to have a colleague,” his only intent, the sermon affirmed, had been to safeguard his congregation. “I must tell you he knew not where to find one he could safely leave his poor flock with,” Mather advised, and it was only the deceased minister’s “lenity, patience and charity” that had “let the sparks die, which … some men had blown up to a dangerous flame.” After the death of the righteous, Saybrook’s minister warned, sometimes “great disorders follow in towns, churches, state & families.”

Lyme’s Ecclesiastical Society moved quickly to secure a successor. Two months after Noyes’s death, it invited Jonathan Parsons, a recent Yale graduate studying theology in his native Springfield with Rev. Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758), “as a probationer for settlement.” It voted three months later to “continue Mr. Parsons in the work of the ministry” and allocated the “just sum” of six shillings to Renold Marvin (1669–1737) “for his service in bringing Mr. Parsons, the present minister, into the Society.” Surviving documents do not reveal whether the Society sought a successor whose beliefs departed from those of Moses Noyes, but Jonathan Parsons later made the difference explicit. “In that day, he wrote, “I was greatly in love with Arminian principles.”

To secure the candidate’s acceptance, the Society offered a generous settlement. It agreed to pay the new minister’s salary either in money or in “wheat at seven shillings per bushel, or rye at five shillings per bushel, and Indian corn at four shillings per bushel, pork at five pence per pound, beef at three pence per pound.” When the Society unanimously confirmed the choice of Mr. Parsons “for the settled minister and pastor” in August 1730, it allocated a parcel of fourteen acres “with the house erected thereon,” along with the income from the parsonage farm and a yearly salary of £100, for as long as the minister remained single. The previous month Parsons, age twenty-four, had sent a second courtship letter to his mentor’s sister Hannah Edwards (1713–1773) in Springfield, who declined his request.

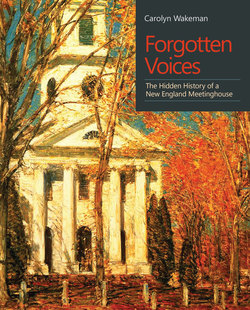

In a eulogy for Lyme’s long-serving first minister, Rev. Azariah Mather warned that sparks of contention smoldering in the parish could soon burst into flame.

On a “fair, cold, and windy day” in March 1731, New London farmer and justice of the peace Joshua Hempstead (1678–1758) noted in his diary that he “went to the ordination of Mr. Jonathan Parsons in Lyme first Society.” The minister later explained that he had “refused to take the oversight of the church” for seven months while struggling with doubts about the validity of “Presbyterian” ordination. When those uncertainties had not resolved on the eve of his ordination, he made clear that he would not be guided by the Saybrook Platform but would take only “the general platform of the Gospel for [his] rule.” Church records note that ministers from New London, Killingworth, and Saybrook’s newly separated west parish conducted the ordination of Moses Noyes’s successor. Rev. Azariah Mather, who had delivered the ordination sermon in Lyme’s north society for Rev. George Beckwith two years earlier, did not participate.

Over almost four decades Joshua Hempstead chronicled his activities in a diary that includes vivid details about weather conditions, farm labor, marriages, church services, and court decisions in New London and the surrounding region.