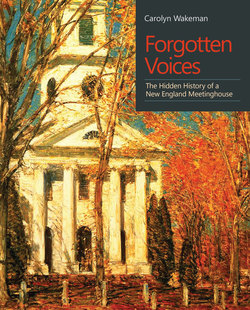

Читать книгу Forgotten Voices - Carolyn Wakeman - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER SEVEN

Finding a Successor

The shocking dismissal of Yale’s rector and senior tutor in 1722 disrupted Lyme’s search for a minister to assist the elderly Moses Noyes.

It was an awful stroke of Providence in taking away Mr. Pierpont, in whose assistance I promised myself much benefit to the place, & much ease & comfort to myself, & it is the more afflictive, because our young men are feared to be infected with Arminian & Prelateral notions; so that it is difficult to supply his place. It was a wrong step when the Trustees, by the assistance of great men, removed the College from Saybrook, and a worse when they put in Mr. Cutler for rector…. Had Mr. Pierpont lived, I hoped this summer to have liberty to come into the Bay.”

Moses Noyes’s letter to Samuel Sewall in 1723 has a melancholy tone. The minister’s acquaintance with the Boston judge stretched back to their youth when Sewall had prepared for college in the Noyes family home in Newbury. Decades later Noyes voiced to his friend a sharp sense of loss after the sudden death of his young assistant. Concern about the influence at Yale of “Arminian” notions, both Anglican tendencies and other departures from strict Calvinism, compounded his sense of personal affliction.

Thirty years had passed since the establishment of Lyme’s church, and Noyes could no longer fully perform the work of the ministry or preach the gospel to those who lived far from the meetinghouse. By the time he drafted a will in August 1719 stating his readiness to leave “this contentious and quarrelsome world,” the town had attempted to secure a successor. The initial choice was Samuel Russell Jr. (1693–1746), age twenty-four, a former tutor at the Collegiate School and son of a founding trustee. In February 1717/8 a Lyme town meeting decided “to go and treat with Mr. Russell, Jr., to come and assist Mr. Noyes in the work of the ministry.” To attract the young candidate, it approved £70 in bills of credit, along with the future use of the parsonage farm and the sale of “one hundred pounds worth of land for the settling of Mr. Russell.” A year later, in October 1719, a town meeting authorized “Mr. Noyes and Mr. Russell, the ministers of this town,” to preach on the Sabbath to those living in Lyme’s north section and “to proportion time as they see fit.”

John Smibert’s portrait of Samuel Sewall captures Rev. Moses Noyes’s childhood friend from Newbury, who unlike his colleagues refused to wear a periwig, just months before the esteemed Boston judge died in 1729. Photograph ©2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Mr. Russell’s assistance ended abruptly a month later. The town paid the young minister a full year’s salary and “acquitted” him from the £200 provided for his settlement, then voted to hire a replacement “for three months on probation.” It also directed a committee to “advise with Mr. Noyes concerning another minister.” Two weeks later, after a majority vote at a town meeting chose Yale’s senior tutor Daniel Browne (1698–1723), after Lieutenant Richard Lord (1647–1727) traveled to New Haven to “treat with Mr. Daniel Browne concerning his coming to Lyme to preach in said Lyme.” No further mention of the second candidate appears in town records. Mr. Browne may have declined, or Moses Noyes may have raised doubts about the Yale scholar’s theological views.

The search had spread over three years when the town reiterated its readiness to hire “another minister to help and assist Mr. Noyes in the work of the ministry.” Inhabitants then agreed in January 1720/1 that “Mr. Samuel Pierpont (1700–1723) shall be hired to assist Mr. Noyes in the work of the ministry for half a year.” To assure the third candidate’s acceptance, the town appointed a committee to “go to Mr. Noyes and get his advice.” Financial entanglements complicated the arrangements. Samuel Russell had used the £200 previously provided for his settlement to purchase land, and the town argued its right to dispose of that land as “a settlement for another minister.” In June 1722 it granted the land to Mr. Pierpont, “the now assisting minister in the town society, if he lives to be ordained in said town society.”

An ongoing dispute about the “use and improvement of the parsonage lot” also needed resolution. Moses Noyes had previously insisted on passing the farm to his heirs rather than to a succeeding minister, but a letter entered in the record book by town clerk Moses Noyes Jr., a month after the hiring of Samuel Pierpont, resolved the controversy. “To the town of Lyme for the preventing of causeless content[ion],” the elder Noyes wrote, “I have thought meet to signify to you that I have accepted and do accept … to leave the parsonage farm to the next incumbent.” Denying that he had “designed any damage” to his successor, the minister claimed there was not “any shadow of grounds to suspect I desire or intend any other [outcome].”

Samuel Pierpont’s ordination took place in December 1722, presumably in the meetinghouse, “to the great satisfaction of Mr. Noyes and the people.” Three months later, in “an awful stroke of Providence,” the new minister drowned while crossing the Connecticut River, allegedly after courting a young woman in Middletown. The Boston News-Letter carried the story of his disappearance: “Essaying to pass over Connecticut River, towards Lyme, a league above Saybrook ferry, in a canoe, with an experienced Indian waterman; a sudden and unusual storm came down upon them, overwhelmed and drowned them.” In April, Pierpont’s remains washed ashore and were buried on Fishers Island. The next month the Boston News-Letter printed an elegy for the young minister composed by Samuel Sewall in Latin.

When Moses Noyes wrote to his friend in Boston, he remarked that Samuel Pierpont’s assistance would have “brought much benefit to the place” while assuring his own “ease & comfort.” Relief from ministerial duties might even have allowed him, late in life, to pay another visit to “the Bay.” Meanwhile, fears that young men at Yale College had been “infected” by Arminian notions made Mr. Pierpont’s loss the more “afflictive,” and Noyes worried how to “supply his place.” The decision for the Collegiate School to leave Saybrook had been wrong, the minister wrote, but choosing Timothy Cutler (1684–1765) as rector was worse.

Rev. Samuel Pierpont’s “lonely grave” on a bluff on the south shore of Fishers Island became a destination for sightseers, and a postcard ca. 1910 showed the slab of red sandstone that marked his burial place. The inscription “Here lies the body of ye Rev. Mr. Samuel Pierpont pastor of ye first church in Lyme” was re-carved in 1924, and the grave marker was later moved to the dooryard of St. John’s Church.

Cutler and senior tutor Daniel Browne had together overseen instruction at Yale, and less than a year after Lyme inhabitants voted to hire Browne as assistant minister, he joined the rector in openly declaring his Episcopal beliefs. At a commencement meeting in October 1722, college trustees relieved Cutler of his duties and accepted the resignation of Browne. Within a month both had left for London, where Cutler accepted orders in the Church of England and Browne died of smallpox in April 1723. As a result of Yale’s shocking “apostasy,” future rectors and tutors were required to affirm their opposition to “Arminian and prelateral corruptions” and declare their acceptance of the Saybrook Platform. A group of twelve Connecticut ministers drawn from the four counties in the colony, among them Moses Noyes and James Noyes, had drafted that detailed confession of faith and formulation of church governance and ecclesiastical discipline in 1708.

A finely detailed wood engraving by Thomas Nason conveys the graceful simplicity of the Congregational church built in 1841, overlooking Hamburg Cove, to replace the original meetinghouse in Lyme’s north parish.

When Moses Noyes wrote to Judge Sewall in 1723, his congregation was shrinking. A second church society on the town’s east side had been established in 1719, and a third parish in the north section would follow in 1724. How members of the original church viewed the diminished size of their parish is not known, but remarks by Jonathan Parsons (1705–1776), who succeeded the elderly minister after his death in 1729, have an edge of criticism. Noyes “often lamented the errors that he feared were creeping in among us,” which made him “backward to have a colleague,” Parsons wrote. After “being left of many on each side … that used to be his special charge, he went on preaching to that part of the town which is called the first parish as health and strength permitted, till he died.”