Читать книгу The Mulid of al-Sayyid al-Badawi of Tanta - Catherine Mayeur-Jaouen - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

The Mulid of Tanta, October 2002

It is October in the Nile Delta. Peasants in small groups of five or six are harvesting cotton. The men, wearing blue or soot-brown gallabiyas, and the women, with colorful headscarves, move slowly among the spiny branches of the shoulder-high cotton bushes. Great sacks, from which the occasional white ball attempts an escape, are piled up around the village ready for weighing. Elsewhere corn is being gathered in: the cobs are spread over the ground to dry while the stalks are stacked to form small huts providing shade for buffaloes. Flocks of sheep wander across the fallow land. To the north, rice is being replanted and the hay piles up on the village roofs. Banana plants grouped together in plump copses bring a touch of green. Clover, potatoes, and cabbages fill the slightest stretch of earth between roads and irrigation canals. Wheat waves in the fields as trucks are loaded with huge cabbages whose leaves will be rolled and stuffed for delicious winter dinners. A few grapevines are grown around here, while a bit further on the scent of jasmine engulfs the country road. It is still very hot during the day but, toward five-thirty in the afternoon, evening falls swiftly, and in a quarter of an hour it is time for sundown prayers. The cold settles, bringing a fog that drowns the shade of sycamore trees bent over by the north wind. Night, and the animals are brought in. On the banks of the canal, the croak of a frog alternates with the cry of a karawan, a curlew with a plaintive call. A few peasants, squatting on their heels at the edge of a dirt track, take advantage of these brief crepuscular moments to wait silently for something, who knows what.

By the time of the evening prayer, all is dark and calm: it is the time of the Sufis.

Every evening this group of friends came together. They worked all day long on the land until their hands cracked. They yelled and screamed at their children and their wives, and they beat their animals. They would become blind with rage. But in the evening they put on freshly laundered galabiyas and performed the night prayer together in the main mosque, saying amen from their hearts as they prayed behind the imam. Then they came to the guesthouse.

Now they were kind and wise. They looked at the toil and the pains of the day with composure, and smiled. They regretted the storms of anger at their wives, their children and their animals. But it was the hardship of life and the harshness of the day. It was that great and unfathomable secret hidden in the fertile earth on which they moved about in perplexity, worry, and anger during the heat of the day.

This is why God had created the evening and hidden the sun in the folds of the unknown for an appointed time. For if the world were an unending day and life were ceaseless toil, men would turn into devils who would not know God. There had to be the calm of the evening when they could marvel at the wonders of the parting day, smile at its harshness and question one another persistently about the secrets of growth and withering. . . .

There had to be this calm every evening, when they could open their hearts to each other and talk.1

Lights go on along all the Delta roads. Everywhere are brick buildings with rebar-filled concrete pillars pointing upwards: everywhere bare breezeblock, sometimes enlivened by flowering bougainvillea. But these are the edges of the roads. Within the heart of the old villages, squeezed into the maze of the original core, there are still traditional mud-brick houses of one story, the roof serving as a home to poultry. Sometimes one sees the yellow steeple of a church, but this is rare in the Delta. Often there are the tombs of saints whose ancient squat domes are painted with a white or green chalk wash. And then there are the mosques. Some are sturdy buildings, others of the Ottoman era have slim minarets, and others still have been carefully restored in the nineteenth century with stucco, colored windows, and woodwork. As the population has increased over the last few decades, so has the number of hastily built prayer halls. The central part of the Nile Delta, so astoundingly fertile, has for long been one of the most densely populated regions of the planet. The smallest village can hold ten thousand to twenty thousand inhabitants. To a person flying into Cairo by night, the Delta is a huge constellation of light. Village sits next to village, town next to town, and the roads are filled with the crazy traffic of a throbbing population. Small pockets of dense darkness are punctuated by the neon lights adorning minarets or calmly broken by gentle reflections on irrigation canals and the branches of the Nile. Somewhere in the midst of all this lies Kafr al-Hagg Dawud, a nondescript village where I lived when I was twenty years old. And then there are the bigger canals, the built-up zones, a few signposts that indicate, more or less, the larger of the towns.

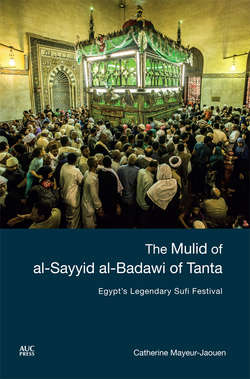

In the middle of the Delta sits Tanta, Egypt’s fourth-largest city. The Coptic origin of its name rings loud and clear with its two emphatic Ts and the long final A. Located on a crossroads of both road and rail, the town is halfway between Cairo and Alexandria, and at the midpoint between the two principal branches of the Nile, the Rosetta and the Damietta. October in Tanta is the time of the Great Mulid of Sayyid al-Badawi and of the annual pilgrimage to the tomb of Egypt’s most popular saint. This saint from the thirteenth century is in some ways famous and in others poorly known, and for many long centuries he embodied the very soul of Muslim Egypt. I have spent many Octobers in Tanta. My first mulid at the tomb of Badawi was in 1987, the one I narrate here was in 2002, and the last one I attended was in 2016. I have spent thirty years pondering the mulid of Tanta.

In the world of Delta saints, Badawi is the master. His disciples, his distant successors, his imitators, and even his predecessors follow his rhythm, and the myriad pilgrimages of the Delta are subjects of his empire. These pilgrimages follow the solar calendar, that of the seasons, of the peasants and their harvests, and not the lunar year of the Muslim calendar: the earth has primacy. In the nineteenth century it was still the Nile flood that set off the mulids of Lower Egypt, which were then in spring and summer. When the flood disappeared from the life of the Delta thanks to the first dams, cotton laid down the law and the great mulid of Tanta was shifted to autumn. The massive rural exodus of the twentieth century, the migrations—both back-and-forth movements and more permanent relocations—and the profound upheavals that have struck Egyptian society have not altered this rhythm. When the cotton and the corn are harvested, when the clouds gather and the first rains fall around Alexandria, the great mulids of the Delta begin. The starting signal is given by the pilgrimage of Shuhada’, a town and district of Minufiya, where the martyrs said to have fallen during the Islamic conquest of Egypt are venerated. This important mulid takes place one week before that of Badawi. The pilgrims of Shuhada’ have just enough time to run from one sanctuary to the next. One week after the mulid at Tanta, it is the turn of Ibrahim al-Disuqi, in the northwest of the Delta, where the celebrations take place along the banks of the Nile.

The Tanta mulid is an incessant back-and-forth between two centers: on the one side is the mausoleum of the saint in the Great Mosque, whose domes and minarets dominate the old town; on the other, a good half-hour walk away, over the railway tracks, is Sigar, the pilgrims’ camp. The festivities begin in Sigar, which was once a village and is now surrounded by urban growth. Fifteen days before the official opening of the mulid of Badawi, red banners are hung by Sufis on the railings of the small local sanctuary of Sidi ‘Abd al-Rahim, a Sufi sheikh who died in 1920. His mulid falls one week ahead of Badawi’s. The fields of corn, where the large grounds of the mulid, called the mal’a or the saha, will be situated, have already been harvested and plowed over. An eight-meter-tall mast has been erected in the center of the site, symbolizing the double presence of the saint of Tanta in this field far away from the mausoleum itself. Throughout the duration of the mulid it stands in evidence of his baraka (blessing). A wide open space stretches all around the mast, in which several large tents have already been pitched. The showmen have come in from all over the Delta, from Cairo and Alexandria, and have already erected two big Ferris wheels, swings, carousels, and shooting galleries.

A lively atmosphere reigns in the Great Mosque of Tanta. Every Friday—the day of rest, when one visits Badawi—is a busy, festive day. All year round the peasants come from all over the region to sell their vegetables, do some shopping, and pay a quick visit to the grand saint of the Delta. In the 1980s formidable women selling fruit and trading in gossip used to sit all along the mosque wall, perched upon stalls offering pomegranates, pears, and guavas. The governorate of Gharbiya province, of which Tanta is the capital, decided to send them off to an out-of-the-way market, and then created a vast semi-pedestrian square around the mosque, enclosed by a wall and equipped with a fountain, all designed to limit easy movement. The demands of modern town planning and the requirements of polite society imposed by modernist Islam on religious events have even had a bearing on the cheerful vivacity of the gossipers. The governorate has a lot to do during the mulid: it must take maximum advantage of the considerable resources that accumulate at pilgrimage time, but it must also direct the pilgrims, supply the site with water and electricity, avoid outbreaks of disease and disorder, control the crowds, collect taxes, and watch carefully over the good reputation of the town and its pilgrimage.

Every year, the national holiday of 6 October in celebration of the 1973 war heralds the mulid. The 7 October is also a day off in Gharbiya: it commemorates the uprising of the town of Tanta, united behind its powerful shrine and its sheikhs, when it rebelled against the French during Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt. National identity mixes with regional pride to build a historic memory, of which the sanctuary of Badawi is the center. Thanks to the days off, the children are out of school, public employees are out enjoying themselves, and there is a crowd around the mosque. The posh districts of the town since the end of the nineteenth century are a good distance from the old heart, but certain middle-class Tantawis like to come and read the newspaper in the café closest to the mausoleum, where they can enjoy an unbeatable view of the constant coming and going.

Lots of villagers and country cousins are on family outings, husbands and wives, mothers and daughters, grandchildren, grandmothers all together. One often comes across Cairenes who have come to spend the day either for business or for devotions: the one never excludes the other.

One single gigantic building houses the mausoleum itself and the Great Mosque with its beautiful prayer hall. The three main rooms of the mausoleum hold several tombs. In the center of each room stands a rectangular cenotaph surrounded by an enclosing wall, or maqsura in Arabic, generally made of wood. The cenotaph is a sort of coffin of wood or masonry set above the spot where the saint is supposedly buried (though this is not necessarily the case) and covered by a green satin drape known as a kiswa. There is a principal tomb in each chamber: those of ‘Abd al-‘Al and al-Mujahid flank the central tomb of Badawi. ‘Abd al-‘Al (d. 1333) and Sheikh al-Mujahid (d. after 1780) were two great sheikhs of the Sufi brotherhood who continued the legacy of the founding saint as embodied by the Ahmadiya. The cenotaphs of other saints, disciples and successors of Badawi, are tucked into the corners of the rooms: the most recent dates to 1978. The pilgrims walk counterclockwise around the claustra murmuring a prayer, sometimes the opening verses of the Qur’an, the Fatiha, or perhaps something more personal. Huge padlocked boxes by the railing are there to receive offerings of money for the baraka. In the central chamber of the mausoleum Sayyid al-Badawi himself naturally enjoys the best spot of all: an enormous dome around which the cries and murmurs reverberate, and a massive cenotaph almost 2 meters high by 2.5 meters long and 2.2 meters wide. A turban and some huge Qur’ans lie on top of the cenotaph, while around it the superb brass maqsura has been polished by countless caresses since it was first forged in the Ottoman era. This railing and a glass pane keep the faithful at a distance from the cenotaph, which is washed in white and green neon light, but each and every visitor grasps the barrier, trying to get as close as possible to the saintly presence. The ardor of silent prayers is equal to the cries and calls of other more vociferous pilgrims, some of whom harangue the saint passionately. A respectable sheikh reads the Qur’an and recites Sufi prayers amid his disciples in a corner of the tomb next to the mihrab, which indicates the direction of Mecca. A woman completely dressed and veiled in white, with her eyes outlined in kohl, hands out cups of water to those who pass by: she dedicates her actions to the saint. A dwarf rolls on the floor next to the maqsura. A man carefully rubs the locks of the railing and then slips his hand into his pocket: the baraka from this contact will increase his virility. A woman removes her headscarf and wipes it energetically over the railings, loading it with baraka to take back home. Suddenly, someone throws a fistful of sweets on the mausoleum assistants and someone else thrusts a few pennies in their hands. This also will procure baraka.

In a corner of the saint’s tomb chamber there is a black stone bearing the imprint of giant feet. They are the feet of the Prophet, for whom the stone suddenly became soft. The footprints of the Messenger are just as venerated as the tomb and on busy days it can be difficult to get close to them. Guards armed with canes try to keep the mass of visitors flowing through, but they hold on and resist. Newlywed couples try to have their photograph taken in front of the holy footprints, though this has been forbidden for some time. Other pilgrims sit down near the tomb in order to savor in silence the incredible atmosphere of the mausoleum. Sometimes, depending on numbers, it can be like a rugby scrum and sharp elbow work is necessary to see the cenotaph. The physical press of the crowd is almost unbearable. Foreheads are bathed in sweat. Babies are brandished in outstretched arms to show them the tomb. Strident ululations fly through the air. At other, calmer moments, one can hear again the discreet chanting of a sheikh, the sobs of a woman entranced, the questions of a child. The visitors look haggard as they exit, and outside the mosque they are assailed by beggars and vendors: lucky charms for babies, pious booklets for the Sufis, incense for all. Further on, there are shops where the pilgrims might buy some chickpeas or halawa, perhaps a plastic toy for the children. One cannot visit Tanta and its patron saint without taking a little something home.

The mulid officially begins on Friday 11 October 2002, with an opening procession. Great colorful tents are pitched all over the old center of the town around the mosque of Badawi, where one can buy chickpeas, the speciality of Delta mulids, or sweaters for the approaching winter, or trinkets and toys. A loud thumping noise attracts attention as a strapping young lad perched upon a huge caparisoned camel beats incessantly upon a pair of drums. A detachment of good-natured soldiers, seemingly unconcerned with discipline, accompanies a small military brass band, which entertains the passers-by, as they wait in front of the house of the khalifa, the successor of Badawi as leader of the brotherhood. This title has for long been more honorific than real, since the Ahmadiya has split up into numerous independent branches. Nonetheless, the role is still a paid position, even if the khalifa receives only a tiny part of the enormous revenue that comes from the tomb and that was once his due. In fact, there are two khalifas, members of rival families. One is a pediatrician and the other a doctor of religious studies; one is very fat, the other of average build. They take turns each year, at the beginning and at the end of the mulid. This year is the turn of the slimmer of the two. He leaves his house wearing a white turban and visits first the nearby tomb of Sidi Salim al-Maghribi. Legend says that this saint preceded Badawi in Tanta, where he announced the latter’s coming and then, on his arrival, bowed down before the true master. Badawi granted him the status of secondary saint, which allowed him to lie in the shadow of his magisterial presence. Thus, the khalifa retraces the steps of Sayyid al-Badawi, and his route restates the blessed history of the town.

The khalifa then enters the Great Mosque of Sayyid al-Badawi on foot. He quickly comes back out again, his head enveloped in white cloth. He is wearing the precious turban of Badawi, a symbol of the spiritual heritage bequeathed to his disciples and his brotherhood, the Ahmadiya. This turban is extraordinarily large and is usually kept under lock and key, away from the crowds, in the reliquary room of the mosque. There are no direct relics, no bones or anything like that. The cult of saints in Islam never exhibits the body of the deceased: only the cenotaph is venerated as a sign of the presence of the saint, since he is ever-present despite his absence, dead but always alive. Occasionally, however, indirect relics are valued, and in the room in question four magnificent silver reliquaries contain personal possessions of the saint: his nine-meter long string of prayer beads, the old chipped cudgel he used to bring back Muslim captives from the land of the Franks, two wooden combs, his red winter cloak, his lightweight cloak, and of course his famous turban sitting upon a silver stand. A century ago the reliquary itself was marched around under a canopy, but now it stays out of sight. When the khalifa comes out of the mosque he mounts a horse with the help of his disciples. A crowd of young Sufis wearing red sashes across their shoulders gathers around him, repeating the name of God—Allah!—while old venerable sheikhs representing the main branches of the Ahmadiya walk alongside. The military escort on foot and horseback follows in merry disorder, with the camel and its lively rider growing ever more uproarious. The procession rollicks along under hails of sweets, howls and cries to the al-Bahiyy mosque. Although completely rebuilt in the 1960s, this was the first mosque of Tanta, then known as al-Busa. It is said that Badawi entered this mosque when he first came from Iraq to end his days in Tanta, and the story goes that he even revived a dead person here. This is why the khalifa comes to this mosque to perform the Friday prayer, thus retracing the same path as the saint seven and a half centuries later. The mosque is also the resting place of a nineteenth-century saint, Sheikh al-Bahiyy, who happens to be a direct ancestor of the khalifa. Three-quarters of an hour later, after prayers and sermon, the khalifa and his escort make a tour of the old town following an itinerary fixed by the governorate. This is the official beginning of the mulid.

At Sigar, the stall owners and fairgoers have not waited for this solemn day. They have squeezed into the nooks and crannies that are left by the urban sprawl. Some have besieged the entrance to the working-class suburb of Settuta in the direction of Sigar, others have settled all along the road to Fisha Salim, the village after Sigar. Of course, the mulid of Tanta is no longer the gigantic fair of bygone days when, in the nineteenth century, it was the biggest in the Muslim world. Nevertheless, for the vendors and showpeople it remains big business, both expensive and profitable. Even the most humble stallholder must pay 300 Egyptian pounds (le) rent for the eight square meters he occupies over some ten days, not to mention electricity (le 50) and various taxes amounting to le 100. The owners of the bumper cars would not blink at paying le 20,000 for ten days since they can earn up to le 120,000 during the mulid. Taxes and prices have risen a lot over the past fifteen years but it is still worth it.

At the entrance to the fairgrounds, the last tattooer of the Tanta mulid has set up his booth: he is a true artist come from Cairo. Although a Muslim himself, he prefers Coptic mulids, where he makes more money tattooing crosses on the wrists of Christians than a bird on a Muslim hand or a few therapeutic dashes on the temple of someone suffering from migraines. He learned his art from his father and grandfather, but none of his children will follow him. Nearby, the flute seller has come from Mit Badr Halawa, the Delta village that seems to provide so many fruit and vegetable salesmen to the markets of Paris. Other mulid specialists have gradually disappeared, like the circumcisers, who were once so much a part of Tanta’s celebrations. A family of circumcisers, the role handed down from father to son, and even from father to daughter, practiced its profession over many long years in a booth next to the Great Mosque. During the mulid other practitioners of the craft would come in from the Delta and set up their little stalls around the sanctuary, and young boys would be brought in by their parents to be swiftly snipped for the baraka. Six years ago, however, the government banned this street practice and one must now take the child to a hospital or clinic. Where have all the circumcisers gone? The mulid is changing. Old attractions, like the Wall of Death, have disappeared. That particular spectacle dates back to the British occupation and the extreme danger involved certainly brought the crowds in. This year there is only one magician’s stall, and one balancing act, and two strongmen enticing the young lads to test their strength. The circus that used to raise the big top on the edge of the grounds takes up too much space and has been moved away from the action. Other attractions have replaced the fun of the good old days. This year the fashion is for photography, and one can get one’s photo taken dressed up as a fantasy Bedouin and sitting on little carriages drawn by outsized cuddly toy donkeys or elephants. In a way this is paying homage to the saint of Tanta, whose very name recalls his Bedouin origins. Other fairground people have joined the first arrivals, and there are several big Ferris wheels and a few bumper-car tracks. A great colorful world of blue, yellow, and red has been conjured up: a world of light in the night. Gigantic neon strips create geometric patterns on the tents and shops that can afford them. The town’s electricity supply is sorely tested and generators have prudently been installed in reserve. This year, as has been the case for a few previous years, the general atmosphere is touched by the economic crisis, and one sees less neon and fewer generators. All this entertainment can be expensive for the fairgoers: the swings cost one or two pounds and chickpeas are three or four pounds a kilo! Never mind, the mulid only happens once a year. . . .

The grounds are still calm since the majority of the pilgrims will not arrive until Sunday or Monday. Once upon a time they came earlier, but now people have to work, the peasants are tied into an ever more rapid rhythm of the harvest, poorly paid government workers have their second jobs, kids have to go to school. The crisis, which has been biting for years in Egypt, has become a lot worse since 11 September 2001: inflation, unemployment, a country on the edge of bankruptcy. None of this is good news for a mulid that lasts a number of days and requires considerable investment on the part of local government and the pilgrims themselves. At the Great Mosque, the police are tense, worried about possible trouble. I have noticed inside the mausoleum an increase over the years of written and verbal bans on this and that, intended to impose a change of behavior: no sitting, no photos, no eating in the tomb. Respecting the rules takes time to catch on. Another rule, recent and unwritten, has been continually repeated over the past five or six years: female pilgrims are not allowed to sit in the mausoleum, but they can visit it, and then they are directed with the children to an adjacent hall. The poor women: prohibited from praying in the prayer hall, prohibited from lengthy worship in the mausoleum, they are left to enjoy their picnic outside the sanctuary. Indeed, not long ago, the colonnaded courtyard in front of the mausoleum served as a common space where groups of people would eat, drink, and sleep together. Blankets and litter and the stuff of human life would be strewn across the marble slabs. Now, during the mulid, the colonnade is occupied by colorful tents with floral patterns that are reserved for more lofty purposes. It is here, starting on Tuesday, that Qur’anic recitations will take place; it is here that officials will be received; it is here that the police will set themselves up. Pushed out of the courtyard by the formality of the official tents, the poorer pilgrims settle around the fountain and in the square, spreading out mats and firing up gas stoves to boil water for rice or tea. This is the campsite of the visitors who do not belong to any particular brotherhood but who wish nonetheless to honor the saint of Tanta. On Thursday evening, for the Great Night of the mulid, the celebrated Sheikh Yasin al-Tuhami will come to this colonnade to sing in praise of the Prophet and the saints. This great singer of sacred songs is originally from Upper Egypt and some ten years ago was not really known in the Delta. Now, however, a quarter of all the tape cassettes being hawked by the roving vendors who have come to the Tanta mulid are of his voice. His image is on all the cassette boxes, with a backdrop of the mosque of the Prophet at Medina, or al-Azhar, or the well-known mosque of Cairo University, or indeed the Eiffel Tower, because he has sung in France at the Théâtre de la Ville and the Institut du Monde Arabe. He is extremely rich. Everyone considers him a saint.

At Sigar, the pilgrims are gradually arriving and settling in. Vans, cattle trucks, pickups, and rented minibuses unload one after the other a mix of blankets, sacks of rice, and stoutly built matrons. The tents are laid out in regimented rows, marking out streets, crossroads, and neighborhoods. At the entrance to each tent an embroidered cloth banner proclaims the name of the sheikh—whether dead or alive—the name of the village, district, governorate, and of course the name of the brotherhood itself. In fact, the color of the banner is itself significant: black is reserved for the Rifa‘iya, red for the Ahmadiya and all its branches, and green and white are used by several brotherhoods, such as the Qadiriya and the Burhamiya. In general, the pilgrims group themselves as a function of brotherhood, locality, and family allegiances. The Qadiris from Fisha Salim, for example, are a group of related families, united by their sheikh and coming from the same village. However, there is also a woman from Benha in their tent whose connection is only one of friendship and habit, and by the relationship she has formed with their sheikh. Every year she returns to stay with them during the mulid. At the far end of the site, on the edge of the fields, about one hundred pilgrims with their children have arrived with boxes and cooking pots, some piled up on camels, others squashed into vans. They are all members of the same clan from the village of Sidud near Minuf, but they are sharing their tent with people from Ghamrin, a nearby town where the sheikh both groups revere is buried. This sheikh died about ten years ago and is the object of an active mulid in Ghamrin. While these tents appear at first sight to be occupied by peasants, many of the younger folk work in Cairo during the week and only return to the village on Friday. Outside the tent the forty-two camels that carried them from Sidud are grazing: inside, straw and blankets cover the floor. The women and children are confined to the rear behind a cloth partition, but they come and go freely in a way that would not be permitted in Upper Egypt. The cooking goes on in this rear section. Another sheet closes off the two goats that will be slaughtered in honor of Badawi on the final night of the mulid. They are shown off to me with pride: livestock is very valuable and it represents great baraka for the brotherhood. It is said that in the 1920s there were two sheep or even two buffalo per tent, but who today has the wherewithal to sacrifice so many animals? Nobody here ever eats meat, except of course during the mulid.

The day drags on with nothing much to do: a bit of shopping, a visit to the tomb, a shot on the swings, fetching water, paying taxes to the local administration, a visit to another brotherhood. Water pipes are smoked and tea is drunk; there is much chat and listening to cassettes of dhikr. Time must be killed before night when the festivities kick off. Peddlers pass by selling sugary sweets, walking sticks, headscarves, small sweaters, and plastic horses for the children. Shoeshine boys offer their services, and this is no extravagant luxury at a time of sudden showers on this sticky black agricultural earth, which clogs your shoes with straw and strips of sugarcane. Wandering musicians and beggars carrying incense come around in search of pennies. It is party time for the inhabitants of Tanta, and what is more, school is out for the children of the town beginning on Tuesday.

Come nightfall on Tuesday the superb illuminations are sparkling. Crowds form around the mast in the center of the tented camp. There are small family groups who have come from Cairo or even villages further afield in Middle Egypt, brought by a sense of personal devotion. They are not tied to any particular sheikh or specific brotherhood: the cult of the saint has long since gone beyond the realms of organized Sufism. All of these pilgrims sitting cross-legged on the ground simply want to spend the evening around the mast. The atmosphere is easygoing: parents sit with children, bands of youths are hanging out, a group of girls sings and dances, clapping their hands, while around them a gang of admirers gathers. There is plenty of laughing and joking, but mulids are not really the place for young girls. Nevertheless, it is Tuesday, there are quite a few of them, they are all locals on their home turf, and fathers and brothers are never too far away. Someone is selling cotton candy, called ‘girls’ hair’ (sha‘r al-banat or ghazal al-banat) in Egypt, someone else popcorn. Swings fly up into the air and little firecrackers explode everywhere. Some of the brotherhoods would have liked to begin the dhikr this evening but authorization was not given: too much noise for the neighbors, who are hoping for some quiet tonight before the two sleepless nights and the decibels that are ahead of them.

Around ten at night the Great Mosque is calm when suddenly three or four cars pull up at the entrance to the sanctuary surrounded by a rush of men trailing an extraordinary atmosphere of joyous zeal. The young sheikh of the powerful Khaliliya from Zagazig, ‘Amm Salih Abu Khalil, has arrived. His disciples, many of whom are educated men and women of the middle classes, including couples with children, state firmly that he is a saint. The chamber of Badawi’s tomb is suddenly full of men and women of the Khaliliya. As the sheikh calls upon God and Badawi, they stand, turned toward the gate of the maqsura with hands raised, responding with repeated cries of “Amen!” that bounce around the dome. Eyes glisten and tears flow. Photographs of the sheikh are handed out to the crowd and then he swiftly departs, shielded from the fervor of his flock by some burly security guards. And so it is for the rest of the week: great sheikhs arrive one after the other to honor the Tanta mulid by their presence, to gather together their disciples and lead one or two dhikrs. Other visitors with no claim to sanctity also feel the need to make an appearance at this national religious event, without of course mingling with the peasants squatting on straw surrounded by goats and children. A minister or two, the supreme sheikh of the Sufi brotherhoods, the Sheikh of al-Azhar turn up for a few religious get-togethers: Qur’an readings, piously dull lectures, flesh-pressing and glad-handing with state-appointed Islamic worthies. The governor is kept busy.

On Wednesday, things get serious. The crowd grows and grows because tonight and tomorrow night will be evenings of dhikr. The old town is almost closed to cars, and peddlers take over, selling trinkets, toys, and incense on the median of the main street that leads to the mosque of Badawi. Trains and buses from Cairo and other big towns bring in pilgrims for the day or for a couple of nights. Conscripts on leave mix with Sufis smitten by Badawi: city-dwellers of Delta origins returning to the villages rub shoulders with youth who are simply out for a good time. The closer to the Great Night, the more holy and auspicious the moment. When night falls, people eat and then perform the evening prayer. Once the plates have been cleared the dhikr begins. Dhikr consists of calling on the name of God, litanies and prayers of the brotherhood, rhythmic gestures as His Name is intoned, often accompanied by chants praising the Prophet and the saints. The Qadiris from Sidud, my camel-owning friends, line up in rows according to age and degree of initiation. Their dhikr is very physical and jerky, the rhythm following the beat of a teaspoon against a metal bar. The man in charge of the teaspoon does not falter as he hammers away for a solid hour. There are no instrumentalists, but a chanter bellows a cappella with the aid of a huge sound system. The young are at the edges and take the opportunity to mess around a bit: they are sweaty and delighted, they are having fun. Every now and then they break off to sip a glass of tea, to check on a restless camel, or to greet a passing friend. The older men—all those over thirty or thirty-five years, married with kids, fit into this category—are not distracted and display unearthly stamina: rhythm is perfect, breathing regular, the prayers known by heart. Many of them smile during the dhikr, eyes closed with toothless grins. Hard faces shine, solid bodies are lithely balanced, and their arms, draped in wide gallabiya sleeves, are precisely extended.

Given that not everyone can hire musicians or sound systems and microphones, people may respond to the dhikr of a neighbor. People stroll from tent to tent searching out the most beautiful and moving dhikr. It often happens that a person will encounter the sheikh and will occasionally change brotherhoods. For the time being, people are wandering, since the dhikrs will not finish until dawn, around four o’clock in the morning.

The inhabitants of Tanta also participate in the celebrations, at least those who live in the old town or around the grounds. They may look down on the peasants, but nobody would sniff at such entertainment, and it provides the occasion to cook some special meals and get out to visit others. For those who have Sufis camping on their doorstep, there is usually a good relationship with them, and over the years people help each other out. And for those groups who are blessed with a particularly venerated sheikh, the links are all the stronger. Of course, the shopkeepers complain of stubborn peasants who buy nothing, of the market being slow, of the decline of the mulid because of general poverty. Frankly, I have always heard these complaints, but it is true that the crisis is sharp.

A young woman stops me in the street and stares: we know each other. Fifteen years ago she was a little girl whom I would push on the swings: now she’s a mother. Her father is dead, as is her uncle, both before the age of sixty. As townies, they expressed the same condescension towards the fellah, the yokels, that the people of Tanta have always shown. And yet they were originally from the countryside, still kept the accent, shared the same beliefs, and were proud of their native village, which happened to be founded by a saint who was also an ancestor. I used to sell cassettes of dhikr in their shop to wary peasants. They would come looking for such and such a singer, and would listen a bit, tapping out the rhythm with their fingers. They would try to bargain, turning the cassettes around and around in their thick hands, peering closely at the box as if this might reveal the contents and lower the price. Sometimes they would carefully reach into an inside pocket and pull out a small cloth purse from which appeared a crumpled bill. Other times, they would leave, unconvinced and worried that they might be being had. And then the shop owner would crank up the volume on the latest hits, trying to pull in the customers with a powerful-voiced sheikh who could melt hearts as he vaunted the Prophet, or perhaps a songstress with a peasant accent trilling wedding songs of love and longing.

The night of Wednesday to Thursday is already a stern test. Sticks of sugarcane stack up in the mulid campsite next to a small dried-up canal. People come and go ceaselessly. Buses, horse carriages, and taxis drive around and around until dawn in the midst of an unworldly commotion. How will they be able to manage tomorrow, the Great Night of the mulid, from Thursday to Friday? At sunrise, the noise of dhikr still rings through the grounds and the old town. The rooftops are washed in thin light and, if one listens carefully, a flute in the near distance cuts through the noise of mingled dhikrs. It seems to whistle on even after everything is silent.

Thursday: all day the prayer hall of the Great Mosque is thick with people. Everywhere, both men and women sit or lie, snoozing or exhausted, at the feet of columns in tight little rows. Rays of sunlight beam through the openwork ceiling, casting a golden aura on the crowd below. Heartless workers smother the prayer hall in a cloud of insecticide that drenches the beautiful carpets with a ghastly smell. Midday prayers today and tomorrow will be filled with people from the mulid. The sheikhs of the brotherhoods will be coming with their delegates and disciples. Prayers in the mausoleum mean turbans and walking sticks, immaculately white gallabiyas and polished shoes, the bourgeois in city suits murmuring Qur’anic verses: outside, the uninterrupted trampling of the crowd, so many feet stomping the floor in unceasing and extraordinary movement. Just covering a dozen meters is tiring enough, but to go from Sigar to the mausoleum is a commando training course that leaves one spent. Passing through the tunnel beneath the railway that marks the line between town and suburbs is fearsome. The cries resound more here than elsewhere, the half-light is just right for clumsy jostling, and the disabled who squat here to beg barely escape being crushed. The crowd pulls and pushes, it wavers for a second, then stands firm. It is a continuous stream that cannot long be diverted by any distraction. One can, however, move forward. Some fifteen years ago, one could hardly touch the ground or choose direction or even escape from the flow. Only the truncheons of the police stationed along the path of the pilgrims could slightly dent the compact mass of brown and navy blue as it swayed like the sea. I was always being told, “You can’t walk there,” and it was true. You needed physical bravery to dive into the scrum. Every year people died, suffocated by the crowd or trampled to death in a stampede. But those days seem to have passed. The crowd is smaller, smothered by poverty: the poor no longer have the money to pay for entertainment designed for the poor. And the middle classes, numerous if discreet participants in the mulid, are not going to risk life and limb wandering through thronged streets.

As the sun sets, a procession follows the khalifa as he goes to pray in the Great Mosque of Badawi, setting off more cheers and applause. He comes from the direction of the Samanud Bridge where he has been greeting the Shinnawiya, a branch of the brotherhood that grew out of the very first companions of the saint. It is another way of celebrating the allegiances between the brotherhoods, even though, among all the ululating women and rejoicing men, almost nobody knows the history. All is banners, drums, and cries. The multitude of pilgrims camped out in front of the mosque are squashed in together, sitting on cardboard boxes. A matronly woman, widowed with ten children, is selling tea with her daughters from a second marriage. She normally lives in Cairo, in the shadow of the great mausoleum of al-Husayn, the grandson of the Prophet, where she scrapes together a living. Next Monday she will have moved on from here to work the Great Night of Sayyida Aisha, a Cairo saint and descendant of the Prophet. At that mulid she will sell peanuts, before moving on the following week to Disuq for the mulid of Sidi Ibrahim. She manages to survive, rolling from mulid to mulid. She loves the People of the House, the ahl al-bayt, all the holy men and women venerated in Egypt who are accepted as descendants of Muhammad. Badawi is one of them.

As night begins so do the dhikrs, more of them and even louder than the previous evening. Canopies have sprung up in the old town and in the run-down streets around the Great Mosque, smaller perhaps than those out at the camp of Sigar, but they are busy and pull in those passers-by who are not truly Sufi. There is a large awning attached to the top of a flight of stairs that stretches between two houses. Beneath it are the followers of Sheikh Sa‘d Ragab al-Rifa‘i from Minufiya. The sheikh was a ticket inspector on the buses in Cairo but came originally from the large Delta village of Bagur, to which he returned after his retirement. Their dhikr is considered one of the most beautiful, and he and his folk used to set up tents at all the great mulids of Cairo and the Delta: I have followed them from mulid to mulid, from year to year. About two and a half years ago, after a short illness and on a day when the sky suddenly went dark, the sheikh passed on in a haze of sanctity. If the miraculous signs and visions appear in sufficient number and the government consents, then the sheikh will have a tomb and a mulid of his own.

In the meantime, a full-size photograph of the holy man decorates the tent and stares out at the new sheikh as the latter launches the dhikr. Before his death Sheikh Sa‘d had chosen his third son to be his successor, and these past few years, after seventeen years of driving trucks in Saudi Arabia, the son has returned to dedicate himself to the brotherhood. Tall and austere like his father, the new sheikh also shares a certain shyness, but not the same silent smile that seemed to understand all of human weakness. He knows that his father was a saint and nobody around here would doubt it. With due humility he prides himself on honoring the memory of his father with scrupulous loyalty so that none of the customs and traditions of the brotherhood will be broken. As he observes the rituals of the dhikr, the new sheikh is careful to follow the path set by his father, and he ends up revealing an unforeseen force that fulfils the expectations of his disciples. Everybody is saying it: he takes after his father.

The dhikr begins at nine o’clock. After the specific prayers of the brotherhood, which all the initiated members recite while sitting, taking their lead from the sheikh, the Fatiha is spoken. It is a moment of real concentration with tense faces and eyes closed or fixed on the middle distance. Then, up they stand and the musicians take over: a violin, a flute, two tambourines, and a darabukka. Voices rise, a tambourine is struck, the rhythm is set, and the dhikr begins. At first slow and full as the performers find the beat, it will grow faster and faster, more and more energetic, almost without end. Two singers, one of whom is famous throughout the Delta, will take turns driving the performance from nine o’clock until three-thirty in the morning. A few years ago it was Sheikh Lutfi, his face disfigured by scarring from burns, who whipped up the dhikr of Sheikh Sa‘d, until one night, returning from a session, he dropped dead. His eight-year old son is here this evening, and he is hoisted onto a chair and takes the mic for half an hour. His piercing voice, still clearly that of a child, delivers the chants of adults, listing the names of the saints venerated by the Egyptians: the descendants of the Prophet, al-Husayn and Sayyida Zaynab who are buried in Cairo; and the Four Poles of Sufism, Sidi Ibrahim al-Disuqi, Ahmad al-Rifa‘i, ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani, and Sayyid al-Badawi, the host of this feast. People are struggling through the tightly packed crowd around those performing the dhikr in order to see the son of the father and to admire his youthful talent.

Passersby stop, the mass grows, the throng thickens, and the musicians climb onto tables and chairs to play over the assembly. Some women standing at the edges are taken by the rhythm, rise up, and join in. Here and there a man falls into a trance and is swiftly and firmly grasped and held up by the sheikh, who leads him, still trembling, to a calmer spot. One particular person, an epileptic, causes serious concern to the sheikh’s cousin, a courteous man who normally works for UNESCO but during the mulid is in charge of security. The son of the new sheikh, named Saad after his grandfather, is a teenager with a gentle face. He lives in Minufiya and has come this evening after finishing his classes at high school. He enters into the dhikr methodically, with concentration, and his father, passing through the rows, adjusts the young man’s shoulders and shifts the stretch of his arms. Some men stop and move off to grab a bite in a corner: leaves of arugula, potatoes in gravy, a chunk of brownish meat bobbing in oil. Tea is continually being served and cigarettes smoked. Night moves on, sweat drips from foreheads, and fatigue causes a momentary falter as the rows of participants break up and drift off. Time for a pause in the dhikr as some people wander home. Others head off to visit another sheikh and there are a few moments of hesitation. But then, tea is drunk and the dhikr starts again, renewed and rejuvenated. Once this point in the night is past, things get even more intense and unfettered. The body, ears, and wounded fingers of the drummers and of the lips of the flautist have been at it for more than four hours with almost no break. At this late stage in the night, the dhikr becomes gradually more free-form. A sharp voice rings out as a little girl is hoisted onto her father’s shoulders and sings the glory of the Prophet. Women slap their palms together and ululate their admiration. A magnificent sheikh of the Rifa‘iya brotherhood arrives grasping a wooden staff carved in the shape of a snake, which he moves from hand to hand. This bears baraka since the snake is the emblem of the Rifa‘is, and it is by swallowing live serpents that the sheikhs of the brotherhood reinforce their charisma. The singer grabs the snake staff and, climbing onto a chair, dances and sings, improvising around the usual themes. The joy reaches new heights as the dhikr intensifies. The chanting follows and seems to be unable to reach an end. And then, in a few seconds, everything slows and, almost brutally, stops. The cousin, uncle, brothers, and sons of the current sheikh gather in the center of the tent and recite together the very last prayers, the closing Fatiha. There is much congratulating and fixing of turbans, addresses are exchanged on small slips of paper, and a final tea is drunk. It is past three-thirty in the morning and all the dhikrs are winding down.

Outside, the night is lit by neon and the crowds are still dense. Streams of people are moving from Sigar toward the station and the town. The grounds have been trampled into a mire of mud mixed with straw and strips of sugarcane. Some people are fast asleep in tents while others are methodically packing up poles and canvas. By dawn, departures have slowly begun, in vans and taxis and trains. The camels are loaded. Most of the pilgrims will be gone before Friday prayers, though some will stay to visit the saint one last time. Everyone is already thinking about the next great mulid, that of Ibrahim al-Disuqi, which starts in a week just a little north of here. Conversation revolves around the concerns of the sheikhs: who is going and who is not, where shall we meet and what needs to be done before then?

Friday is the end of the mulid. The pilgrims have already left, but the town is still solid with people who want to perform midday prayers at the mausoleum of Badawi. A final procession wraps up the mulid, watched over by the inhabitants of Tanta, for whom the entire event, as the expression of their town, inspires a particular pride. The khalifa is on horseback for the last time, his head swathed in the turban of Sayyid al-Badawi. Sometimes the parade is huge and lasts several hours, to the great joy of the inhabitants, but this year, in accordance with the demands of the governorate, it will be limited. A brass band, a few mounted police, some on foot, the khalifa on his horse, and some boys and girls in donkey carts laughing and shouting. This year there are no floats representing the guilds, no parade of the Sufi brotherhoods. After Friday prayers in al-Bahiyy Mosque, the khalifa finishes his ride through the streets and then returns to the mausoleum, to restore the turban of Badawi to its rightful place in the reliquary. The mulid is over.