Читать книгу The Mulid of al-Sayyid al-Badawi of Tanta - Catherine Mayeur-Jaouen - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction:

‘Popular’ Islam in Egypt

The first time I visited Tanta, in the heart of the Nile Delta, I was twenty years old. It was winter. It was not love at first sight: the town was dusty, sad, and dull; the weather was cold and damp. I knew nothing then of the saint, Sayyid al-Badawi, who was venerated there, nor of the pilgrimage, the famous mulid and the Sufis of the Delta.1 Since that time I have dedicated continuous research to all of these, and decades of inquiries have still not exhausted my curiosity or passion, or indeed, the very subject. The study of Badawi and the mulid of Tanta is not like writing a tidy monograph based upon accessible histories. It is more like casting off into a storm-tossed sea. There are hardly any sources, just some rare passages in old chronicles, some fevered hagiographies, ancient legends transcribed in the nineteenth century, stories passed down by oral tradition, and ranting diatribes. I had no real archives to go on, but I could and did visit the mulid continually over the years, as well as the surrounding countryside and its mausoleums. To have begun this field research at the threshold of my adult life contributed greatly to making me who I am. The promise made to friends, to whom this book is dedicated, and made to myself has to be kept: it is time to tell the tale of what was long the greatest pilgrimage in the Muslim world, a tale that belongs to the intimate heart of Egypt’s history.

An article on Tanta in the first edition of the French-language Encyclopédie de l’islam in 1934 presents the town as a hotbed of fanatics galvanized by the quasi-pagan cult of a saint of mythic proportions, the famous Sayyid al-Badawi (1200–76). The rather obscure life of this saint had, since the fifteenth century, led to the creation of the most remarkable legend of all Egyptian hagiographies. As for the mulid of Tanta, the majority of Western writers who had devoted a few lines to the subject simply saw it as the distant descendant of the ancient pilgrimage of Bubastis dedicated to the cat goddess Bastet, which was mentioned by Herodotus, and thus a scene of barely concealed paganism, mythology, and freakish phenomena. Over several centuries the mulid of Tanta, established in a rather modest little town, was recognized by the chroniclers themselves as the biggest in the Muslim world, bigger even than the Hajj to Mecca. It was also the most rowdy, scandalous funfair and a place of debauchery.

The first Orientalists who studied the mulid of Tanta were obsessed by this reputation and neglected to ask about the faith that had drawn and continued to draw so many Egyptians to the mausoleum of Badawi. What did the saint represent to them? What role did his brotherhood play in the cult? What exactly is this popular Egyptian Islam, of which even today the mulid of Tanta constitutes the most spectacular manifestation?

This Islam is not that of the Sufis, which is supposed to contrast with the scholarly Islam of the ulema, but rather that which constituted a shared culture for all up until the end of the nineteenth century and even into the interwar period. From the 1880s, the rupture caused by Islamic modernism and its success as the dominant discourse in the twentieth century have led many commentators and the Egyptians themselves to a mistaken reading of religious tradition, seen as a tissue of backward superstitions. Islamic modernism saw itself as an attempt to adapt Islam to the contemporary world, and it implied a rejection of tradition as lived, which was presented as sclerotic and burdened with useless dross, including the cult of saints. In reality, Egyptian ‘popular’ Islam (the Islam of ordinary people) is deeply and intimately shaped by Sufism, the quest for union with God, which since the thirteenth century—the very era of Badawi—had gradually formed itself into mystical brotherhoods, the turuq or paths. We are not contrasting here a sublime and pure ‘original’ Sufism with a degraded, bastardized version of the Sufi brotherhoods and coarse devotions. In both cases, we must clearly reject a two-tier model that supposes the existence of a popular rural illiterate Islam, that of the cult of saints, which is rejected and condemned by an Islam of the towns and of educated elites, that of the mosque and the jurist or of the mystical sheikh. Peter Brown’s essential work on the birth of the cult of saints in Christianity was of use to me as a starting point.2 He strongly rejects the ‘two-tier’ model, which sets a religion of the elites against a religion of the masses, who are supposedly more inclined to devotion to saints and more receptive to belief in miracles. This model leads nowhere in that it does not incorporate historical changes in which the authorities (bishops in the case of Christianity) played a central role in the creation and rapid expansion of the religion of the people.

One can see just what a specialist in the cult of Muslim saints might extract from Brown’s analyses, even if within a context of very different practices. Of course, Christian saints—qiddisun in Arabic—are not Muslim saints: the Muslim hagiographies call them salihun, the just, or awliya’, friends of God; and Sufism sees them as the successors to the prophets.3 For Muslims, sanctity (expressed by the root q-d-s) belongs in the strictest sense only to God. It is only proximity to God (walaya) that defines Islamic saintliness: the double meaning of the root w-l-y—which refers to links of proximity and intimacy as well as relations of protection and patronage—also evokes the twin faces of sanctity that look both toward God (walaya) and men (wilaya, which designates also the exercise of power). Another major difference from Christianity is that Muslim saints are considered as the successors of the prophets, and especially of the Prophet Muhammad, who in a way completes and concludes all previous prophetic forms. Thus sanctity is regarded more or less as accepting the model of Muhammad and proceeding within the light of Muhammad. In the hagiology drawn up by Muhyi al-Din Ibn ‘Arabi (d. 1240), all the typology and hierarchy of the saints grow out of this prophetic inspiration.

Despite the differences in terminology and theology between Christianity and Islam, the examples of the saintly man recognized during his lifetime and then venerated after his death are not irredeemably different. Powerful dynasties and ulema within Islam have also constantly favored the cult of saints, and the social and political authority of saints cannot be denied. Moreover, the two-tier model in Islam, ever-present in scholarly literature since the advent of modernism, cannot be defended historically. Religious science (‘ilm) and mystical understanding (ma‘rifa) are not in opposition. Many Sufis have been ulema, and not long ago almost all the ulema were Sufis. The cult of saints thrived in the town as in the field, and among the lettered as among the rustic. Naturally, there are Sufis and there are Sufis: some are educated and some are illiterate; some are the disciples of great mystics, others have simply followed their forefathers by joining a brotherhood as a child. One sheikh performed the dhikr—the remembrance of the name of God—in a low voice, while another was accompanied by pipes and drums. All the diversity of individual aspirations, all the nuances of collective belonging must be depicted in order to express both the variety of Egyptian Sufis and the profound similarity of their common heritage, of their vision of a world shaped by God and in the light of Muhammad. Even the hagiography of Badawi, the most uncouth of saints, and the terminology of his illiterate followers bear the stamp of the most elevated classical Sufism, the most elaborate theories, and the loftiest mystical aspirations. The cult of Badawi, which is steeped in the rural, has provoked debates and censure, but also waves of immense piety across social borders, such that he has become a national saint, a symbol of Egyptian Islam. In reality, Egyptian popular Islam is a fully-fledged, coherent culture previously shared by all—despite real criticism and strong tensions between the two ends of the spectrum—but today ignored and denigrated by the dominant ideology of modernist Islam.

Nonetheless, simply demonstrating the vitality of Sufism in all its manifestations and the profound unity of popular Islam does not answer all the questions. Popular religion within Islam has a real autonomy, as it does within Christianity. It is probably better these days to talk of ‘popular religiosity’ in order to indicate that one is referring to a form of piety, not to another religion, and to practices, not to beliefs. Such caution is advisable, but the term ‘popular religion,’ imperfect as it may be, evokes more bluntly the difficulties of the subject and has the advantage of being better understood by nonspecialists. Within the tales of miracles and practices at the tomb one can see the undoubted face of a popular Islam, which is certainly not a different religion for the lowly folk, but neither is it “simply differentiated use of common materials.”4 The study of specific examples within Islam, as in Christianity, shows that in the matter of religious practices concerned with saints, there are real differences between town and country, but also between the districts of the same town, between the many brotherhoods, and between social categories (for example, the guilds in earlier times). In certain Ottoman hagiographies, as in oral traditions in general, the body of the saint, like the body of the devotees, is spotlighted in a rather bawdy, exhibitionist fashion designed to offend. The tone is obviously very different in the emasculated hagiographies that flourished in the twentieth century. This does not mean, however, that one is opposed to the other, or that the wild should be excluded by the more manageable. On the contrary, the conscious division of roles appears to me to be the rule, between saints who are masters of themselves and frenzied ecstatics, between sober brotherhoods and drunken brotherhoods, between mausoleums in the center of town and small domed tombs in remote rural regions. None of these apparent clefts have managed to break the fragile balance, even if there is always a tension between the extremes of expression within a shared Sufi culture.

In order to understand the issues of Egyptian popular Islam, one most look more generally at those of popular culture. The cult of saints is embedded within the wider world of Egyptian popular culture. Songs of marriage and mourning, rituals of birth and burial, folk tales and ballads and music, visits to shrines and mulids all form part of the same vision of the world. This folk culture is well known from the work of anthropologists, but the Orientalists have left it to the ethnologists and dialect specialists to scrutinize vernacular customs and tales. The majority of researchers studying this part of the world have accepted Islamic modernist discourse because they have been, consciously or otherwise, shaped by the post-Tridentine notion of the ‘excesses’ of popular piety and of superstitions. (The two influences are, in any case, not incompatible.) In both cases, popular religion is seen as an exuberant and irrational form of religion that it is best to supervise, censor, and perhaps suppress. The tendency to study Sufi Islam through the brotherhoods, and preferably the reformed brotherhoods, has given too many researchers a clerical and sanctimonious vision of Egyptian Sufism, whereas it is adamantly unruly. The words ‘excess,’ ‘abuse,’ ‘superstition,’ ‘magic,’ ‘deviance’ continually flow from the pens of excellent authors who are blocked by a normative vision of what Islam should be, and are more generally paralyzed by what they believe to be respect for religion. Many of them share, more or less, the condemnation of inappropriate innovation (bid‘a) and the quest for exemplary Sunni behavior. The absence of a firm vision of what is truly a society is added to these ideological assumptions: why could these pilgrims not eat, play, or sleep? Why do they have to be ascetic? Does piety imply seriousness?

In this striking disinterest in the religion of the humble, Boaz Shoshan’s book on popular culture in medieval Cairo is an exception.5 He covers several themes with great panache, echoing Barbara Langner’s wonderful analysis of Egyptian popular culture in the Mamluk period,6 but once again, the field is limited to Cairo and the countryside is ignored. As for Egyptian scholars, research into the cult of saints has been even more firmly smothered by the polemics arising from modernist Islam. The documents available for the historian of the contemporary period are pamphlets and apologies, indignant defenses and passionate attacks, but nary an academic study per se. Doctrinal Sufism or urban history would appear to be the only possible subjects for an Egyptian scholar of religious history.

Under the term ‘popular religion,’ and drawing inspiration from a framework proposed by André Vauchez for medieval Christianity,7 the Islamic specialist can address three categories of religious phenomena: the manifestations of a folk culture specific to rural societies with its rites of passage and its relationships between the living and the dead; the more or less spontaneous popular religious movements, such as the appearance of mahdis and those who rebel in the name of religion; and lastly the piety of Sufi brotherhoods and the pilgrimages that they organize. These categories, however, should not be seen as entirely discrete and they illustrate that no single theory can be applied to popular religion. Let us bear two things in mind: there is a folk culture distinct from, but still closely linked to, the Sufism of the brotherhoods, and Egyptian popular Islam is not a jumble of superstitions.

But what does ‘popular’ actually mean?8 Who are the people in question? The humble who live in town and countryside, or the rural as opposed to the urban, or even ‘lay’ Egyptians rather than the men of religion, the sheikhs and ulema? Does ‘popular’ mean created by the people, received by the people, or perhaps destined for the people? This question is particularly relevant as regards pilgrimages and local cults, and we shall see to what extent the Egyptian state, from Mamluk emirs to the current regime, has played a decisive role in the growth and organization of the mulid of Tanta. The cloak of civic religion that often covers festivals in Egypt illustrates the limited spontaneity of mulids.9 Expressing veneration for the saint has taken on different appearances depending on social environment, and even on cultural division, which is not exactly the same as the former. Medievalists’ notion of ‘civic religion’ helps us to reflect on what Copts and Muslims share about their mulids, and to understand the similarities and differences between Coptic pilgrimages and Muslim mulids.10

As for Tanta’s mulid, town versus countryside represents a fundamental split. For centuries it was very largely rural populations who made the pilgrimage to Tanta, although people of Cairo also attended. The mulid made Tanta one of the biggest towns in Egypt. It was a time of encounters and exchanges, of intersection between worlds that were intimately linked in the Mamluk and Ottoman periods but became quite distinct in the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries: today the borders are more and more indistinct. The countryside of the Delta has become urbanized and the towns more working-class. The culture of the poorer districts of Tanta is not exactly that of villagers come to town for the pilgrimage, but it is definitely foreign to that of the town’s modern areas.

In Egypt, the adjective ‘popular’ (sha‘bi), in the sense of ‘of the people,’ took on a particular connotation in the Nasser era at a moment when interest was being shown in popular literature. Egyptian Arabic also has the term baladi, which signifies a certain authentic rusticity. However, for university-educated Egyptians shaped by Arab nationalism, the more one speaks of ‘the people,’ the more careful one is to distance oneself from them. The intellectuals of the interwar period and of the 1950s, themselves a product of rural environments, cultivated a mix of fascination for and rejection of the people of the countryside who flocked to the mulid of Tanta. In their eyes, the religion of the rural could only be uncouth, emotional, and loaded with superstition, a close cousin to the magic of ancient Egypt. In no way could it be a coherent system or a harmonious and structured interpretation of the world.

One must reject the all too current idea that has been repeatedly spread by modernist Muslims of a bastardized, degenerate popular religion that is a sad deformation of a once-pure and spotless Sufism, or of a mistaken popularization of a learned religion of the written word, or even the expression of an anti-Islamic paganism that bears no relation to true Islam. On the one hand, the cult of saints in Egypt, as elsewhere, has been deeply influenced by textual hagiology, and its models are also those of an Islam subjected to the law and those of the ulema, whose learning is just as esoteric as exoteric. We shall see Badawi venerated by the learned as well as by the ignorant, by Cairenes and by country people. This man who left no writings possessed a knowledge that—in his hagiographies of course—could confound the most erudite of scholars. And we shall also see personalities of great solemnity, whose characters, one might imagine, would have kept them at a great distance from our truculent saint, come to be interred in the shadow of his tomb. On the other hand, the systematic rejection of superstitions (khurafat) and inappropriate innovation (bid‘a) in the name of an intangible Islam implies value judgments that a historian should shy away from. If one hopes to understand the Sufism of the folk milieu (and it does indeed take on a different face from other milieus), one must blithely accept what is, without fulminating about what should be. There is no point in exaggerating the bubbling excitement of the Tanta mulid, as certain Orientalists and modernist Muslims have enjoyed doing, or in discarding the customs that were and are practiced there as un-Islamic or anti-Islamic.

Therefore, we may speak of a popular Islam and also an Egyptian Islam, though this will likely raise eyebrows among those who claim to defend the universality of Islam by denying at all costs its historical and anthropological expression. However, one would have to be truly ignorant to deny all that is Egyptian in the cult of Sayyid al-Badawi and his pilgrimage. Of course, there are other great Muslim pilgrimages elsewhere with funfairs and markets attached, but their history would be different. In Egypt, the fundamental role of political authority and the power of the Land of the Nile have shaped a religious landscape without equivalent throughout the Near East. And the exuberant and public expression of a particularly joyous popular piety has remained to this day a characteristic of Egyptian Muslims in their own eyes as well as those of their Arab neighbors. The roots of this piety hark back to the Mamluk era (1250–1517), when the essence of the Egyptian religious landscape, profoundly and intimately shaped by Sufism, was constituted.

The study of popular Egyptian Islam means diving into a polemical subject of controversies and denials, as Samuli Schielke has shown in his thesis.11 It also requires methods adapted to a multifaceted subject that is difficult to grasp. In order to do justice to the subject, I have chosen the longue durée perspective. This, of course, was the common favorite of traditional studies of popular religion in Islam as conducted by the Orientalists of the nineteenth century and by folklorists, who were very interested in the mulid of Tanta. In general, they would end up affirming that nothing had changed or that “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.” This led to the development, as regards Tanta, of the mythical idea of a pharaonic pilgrimage in which the cult of Sayyid al-Badawi was simply a recent reincarnation with an Islamic veneer. Popular religion, springing from the rural and the humble, would thus belong to a continuum of agrarian religions in continuous existence and bereft of history. The lack of specific and plentiful sources on the subject gave space for these lazy explanations, which were taken up by the general public because of the attraction of Egyptology and an ignorance of Sufism. The characteristic features of a popular cult—carnival atmosphere, misbehavior, the sacred and the profane—were to be explained by looking back to antiquity, which was a way of emptying it of all meaning.

Convinced that popular religion has a history, I have chosen to set myself up as both a historian and an anthropologist in order to examine the mulid of Tanta. Instead of considering this long time frame as an expression of something that does not change, I have endeavored to see within it signs of ruptures and evolution, while acknowledging any continuity. Above all, I have tried to approach the popular culture of Egyptian Islam not as a jumbled residue of medieval times but as a coherent culture that makes sense to its adherents. Instead of setting the mulid of Tanta as a marginal event in Egyptian history, I have given it its rightful place, in the center. An examination of Egyptian pilgrimages reveals that continuities and ruptures have occurred not only within the cultural and religious history of Egypt, but also within the political and economic history of the country. The mulid of Sayyid al-Badawi is far from being a single case study; instead, it turns out to be a marvelous observatory from which to view changes in Egypt since the Mamluk period. Better than any other phenomenon, it reveals the silent realities of the history of those about whom we know nothing.

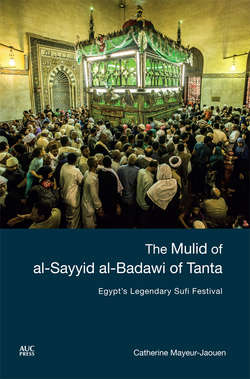

This book opens with an account of the Tanta mulid of October 2002. The aim is to bring alive the central act around which this book will turn. At one fell swoop we meet the saint, the Sufi brotherhoods and their ceremonies, the funfair, the relationship between the pilgrimage and the town itself—indeed, all the elements that we shall examine throughout the book. It is within the light of this anthropological perspective that the history presented thereafter will make sense.

The saint, his legend—itself the subject of a long construction of hagiographic layers—and his importance in the history of Egyptian Sufism will follow in chapter two. Badawi is a type of popular saint, the ‘possessed,’ of which Egyptian hagiology is particularly fond. The fact that he has so readily fulfilled the idea of a rural Egyptian saint has made him a national figure to which a considerable load of folklore has been attached. Similarly, the Sufi brotherhood, the Ahmadiya (covered in chapter three), that Badawi is reputed to have founded is a typically Egyptian brotherhood which meets the needs of a very largely rural community. All the same, from the end of the Mamluk period the stigma attached to the Ahmadis as scandalous twirling dervishes gradually faded and the Ahmadiya spread throughout all Egyptian society and all Sufi tendencies. This success was closely linked to the triumphant popularity of the mulid, and it made the Ahmadiya the best known and most important Sufi brotherhood in Egypt until the present day.

Once this foundation, which defines the very heart of the cult, has been laid, the next three chapters will present three different periods in the history of the mulid. Chapter four retraces the origins of the mulid, from the Mamluk to the Ottoman era, where political power played a decisive role at several moments in the growth of the cult of Badawi. The nineteenth century (chapter five) describes the historical height of the mulid, along with the commercial role played by the fair: the extension of the town of Tanta, initially due to the mulid, ends by damaging the mulid. In chapter six, the twentieth century witnesses the decline of the pilgrimage and its changing nature in the face of urbanization and modernization. The mulid of Tanta thus reflects the mutations of Egyptian Islam itself.

Finally, chapter seven echoes, ten years after the mulid of 2002 described in the first chapter, the anthropological experience that nothing replaces. Egypt has changed a lot, the economic crisis has deteriorated even further, the revolution of 2011 has changed everything. Nevertheless the mulid of 2012, under the regime of the Muslim Brotherhood hostile to the cult of the saints, testifies to the impressive resilience of the mulid of Tanta.