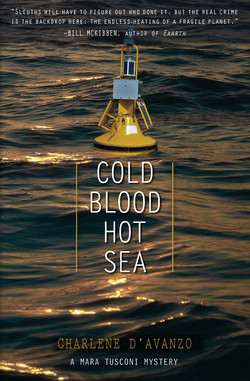

Читать книгу Cold Blood, Hot Sea - Charlene D'Avanzo - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

THE SHIP RESUMED SPEED. IT was time for the senior scientists—me, Ted, Harvey, and Peter—to gather in the tiny lab off the fantail deck and review the deployment schedule. Regrettably, the meeting also included Seymour Hull.

Seymour, whom I’d nicknamed See Less Dull, was department chair and in charge of things that mattered, like grants. I refused to butter him up, and the man resented me.

He also could appear out of nowhere. “Mara, I need to speak with you.”

I spun around.

Seymour’s thin lips formed what could pass as a smile.

“Our meeting’s now.”

He held up my Science Today paper. “This will take a moment.”

I waited.

He licked his lips. “Your paper.”

“Yes?”

“You made a rash prediction and didn’t pass it by me.”

“Pass it by you?”

He waved the reprint. “Incorrect projections reflect badly on MOI. Not just you.”

“Scientists sometimes make risky predictions. It’s a judgment, and it’s why they took the paper.”

“I don’t think so.”

“What?”

“They published it because the author was a Tusconi.”

I stepped closer and growled, “I do not use my father’s name to get ahead. They took it because I’m an excellent scientist.”

“Excellent?” He pointed to my nausea patch. “You can’t even handle conditions out here.”

I snatched the paper and marched toward the lab. That Seymour would throw my dead father’s name in my face was obscene.

Seymour called out, “The Prospect Institute. More unwelcome publicity for MOI.”

Harvey caught up with me. “That looked like a nasty interaction.”

I quickly told her about the hacked emails and Seymour’s accusation. “No suggestion I consult MOI’s lawyers.”

“He wants you to stew for a while.”

“Yeah.”

“And, Mara. What can you do about the email?”

“No idea. They don’t teach you this stuff in grad school. I’ll talk to Angelo when we get back.”

Angelo de Luca, my godfather, is my only family. Twelve years ago my parents died in a research submarine accident. I was nineteen when my world fell apart. Angelo helped me try to make sense of the senseless and is as devoted to me now as I am to him.

He’s my drift anchor in a rough sea.

We squeezed into the lab for our planning meeting. Head scientist, Harvey led the discussion. “We’re on schedule with the deployments. Questions?”

“When can we look at CTD data?” I asked.

Tethered to the ship by high-strength line, the Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) profiler drops through the water and records real-time temperature and salinity from the surface down. Cutting-edge technology my parents’ generation could only dream of.

“The profiler’s already downloading,” Harvey answered.

My throat tightened. What if—?

Peter asked, “Who’s up for this afternoon’s deployment?”

Ted gestured toward me. “It’s Mara’s turn.”

“What’s the report on that loose buoy?” Harvey asked.

We all turned toward Seymour, who shrugged. “Chief mate’s looking into it.”

Not a satisfying answer. Surprise telegraphed around the room.

“The buoy wasn’t well secured,” Ted said. “Are there inexperienced crew aboard?”

Standing near the exit, Seymour said, “I really don’t know.”

Peter met my look and raised an eyebrow. Figuring we were done, I was halfway out of my seat when he asked a question. I sat back down.

“I bumped into a guy in a passageway who’s not at MOI. Who is he?”

Across from me, Ted fidgeted in his chair.

Seymour answered the question. “John Hamilton’s a friend. He runs an aquaculture startup and is interested in our research. We had room, so I invited him.”

A little odd but not worth ruffling Seymour’s feathers.

“Seymour?” Peter said. But Seymour had left.

I looked at Peter. “Something wrong?”

Peter stared at the door. “Not sure.”

Harvey and Peter filed out of the lab, and I started to follow. Ted said, “Mara, have a moment?”

The small space was littered with equipment, and we stood a few feet apart. Although MOI hired Ted two months earlier, he’d been in the Caribbean doing coral reef research. I’d barely spoken with him.

I’d forgotten how attractive Ted was. A bit of blond curled at his neck and his sunburned face looked in need of a shave. Both fair-haired and tall, he and Harvey would make a damn good-looking couple.

Ted had a good six inches on me, and I didn’t want to talk to his throat. I stepped back a bit. “What’s up?”

“The Prospect Institute email. Want to talk about it?”

I took a breath and felt my back muscles relax. “That’d be terrific. I’ve never dealt with anything like this.”

“That message flabbergasted me. What’re you thinking?”

“No time to think.”

I waited for the seasick joke, but he didn’t say a word.

“Maybe I should be proactive. You know, contact the papers.”

“I have a close friend at the Portland Ledger,” he said. “We were college roommates. If you want, I could talk to him. Or you could, of course.”

“I’ll think about it. Ted, thanks a lot.”

He squinted and stared down at my eyes.

I tensed. Someone other than my ophthalmologist examining my eyes felt pretty weird. Maybe this was Ted’s idea of a creative come-on.

“What?”

“Your eyes, Mara. They’re really an unusual color. Forest green. What’s the genetics—I mean, the color of your parents’ eyes?”

Good. A scientific, not romantic, interest.

“Blue from my Irish mom and brown from Dad, the Italian side.”

“A great combination.” Ted’s smile set off two faint dimples in his cheeks. His eyes searched mine in the normal way, and he left the lab.

I had to be careful not to assume the worst in men. The hurt of Davie’s secret affairs was still raw after five years. Nevertheless, being overly suspicious wasn’t a good thing.

Harvey stuck her head in. “You still here?”

“Ted asked about the email hacking. He also wanted to know about the genetics of my eye color.”

“That’s so t—um, so telling. I mean, that he’s a scientist. You do have gorgeous eyes, Mara. With long auburn hair? Killer combination.”

She scurried off.

I was sure Harvey was about to say “that’s so Ted”, which meant she knew him pretty well. Much as I appreciated her high regard, the comment about my physical features seemed like an intentional digression.

Back out on deck, I itched to check out the CTD data, but the weather was deteriorating fast. As Intrepid pitched from side to side, I made my way to the railing to inspect the sea state. Twice, I nearly tripped on a cable.

I grabbed for the railing and gasped. Row after row of steep-sided gray-green waves threw angry spray at the leaden sky.

Damn. Out in the brisk air, I felt okay. But straining to read numbers on a swaying monitor would not be wise.

Still, I really wanted to see temperature data. Just a peek. Legs wide for balance, I duck-walked to the lab, plopped in front of a monitor, and logged on.

I quickly found CTD data. My heart sped up as graphs appeared on the screen. Sliding side to side in the tethered chair, I leaned forward and squinted to make out the black temperature line. What was the scale? A ten—?

That was it. I’d crossed the Rubicon. In an instant, I felt dreadful—cold, clammy, faint. Stupid, stupid, stupid. I rushed out of the lab, sat down on a cable box, and drank in cold air.

Down in the mess, everyone else ate lunch and chatted away. Alone in a corner booth, I sipped hot tea and nibbled dry toast. First Mate Ryan walked up. Usually full of blarney, he touched my shoulder and spoke softly. “Dr. Tusconi. Can I get you anything? More tea?”

I looked up. In the shadow of his tweed cap, Ryan’s blue eyes were all worry. “I’m okay, thanks. Hey, tomorrow I want to hear about your family’s farm in Ireland.”

Ryan wasn’t gone a minute when Peter slid into the bench across from me. “You don’t look so great.”

“My patch isn’t doing the trick today.” I didn’t want to admit it was my fault for trying to read CTD graphs.

“Maybe it’s something you ate,” he said. “For this afternoon’s deployment, I can take your place, no problem.”

I blew out a breath and looked down at my hands. While accepting Peter’s offer made sense, he didn’t understand possible consequences. Of the twenty scientists and crew on board, Harvey and I were the only women. Others—Seymour, maybe even Ted—might think I was a girl who couldn’t cut it. On the other hand, in my present state my reflexes would be slow. I’d be responsible for a halfton instrument on a shifting deck with people around.

I reached for his hand and squeezed it. “Peter, that’d be terrific. Buy you a beer when we get back.”

“You’re on.”

When we reached the next station, the weather was worse and sea rougher. Clearly, I’d made the right decision. I felt better in fresh air than anyplace else. So even though I couldn’t supervise the deployment, I could join the others and watch it.

Out on deck, I found a good viewing spot under the winch platform. Above me, Ryan operated the winch that hoisted buoys up and dropped them into the water.

The angry sea made deployment tricky. Peter and the crew struggled to keep their feet under them, and communication was a challenge. Above the growing howl, Ryan and Peter shouted back and forth. Finally, Peter signaled he was ready. With a groan and a high whine, the winch came to life. Cable slowly peeled off the reel. As if waking from deep sleep, the buoy shuddered. Ryan played the winch so the hydro-wire tugged at the dead weight and inched the massive buoy up off the deck to ninety degrees.

The buoy was almost upright when Peter halted the operation. Reels droned down and stopped. Three guys in orange jumpsuits, legs wide, held guy wires tight and fought to keep the buoy steady as the ship did her best to topple them. Peter peered at the instruments one last time, then backed way. He signaled for the winch to slide the buoy to the open stern. Ryan powered up the reels and shifted gears.

Braced against the ladder, I was snug in my jumpsuit, wool hat, and fleece-lined boots. The wind’s bite on my face, wet with sea spray and rain, faded as I fixed on the buoy’s ride from ship to sea.

The taut hydro-wire held the buoy steady as Ryan slowly advanced it toward the stern. Peter yelled “Halt!” and Ryan slid the gear to neutral. Peter squinted at the buoy and frowned. Something about that buoy troubled him.

Peter signaled Ryan to power the winch once more.

What happened in seconds was slow motion to me. In frame one, the hydro-boom held the buoy upright, seaward of the stern. In the next, the ship pitched up. Like an enormous pendulum, the buoy swung back toward Peter.