Читать книгу Cold Blood, Hot Sea - Charlene D'Avanzo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

MY FATHER ONCE SAID, “WHEN you step aboard a ship, you leave solid behind for that vast unseen.”

I rounded Maine Oceanographic’s biology building at a trot—and stopped dead mid-stride. Goddamn, she was regal. Royal blue against the blood-orange April sky, hundred-fifty-foot research vessel Intrepid waited patiently for us, her mooring lines slack over yellow pilings.

Skirting a cart loaded with long skinny bottles, I all but skipped up the gangway and stepped aboard. Intrepid swayed with the incoming tide. My leg muscles tensed, and I checked the nausea patch behind my ear.

Yeah, I’m an oceanographer who gets seasick. Dreadfully, embarrassingly seasick.

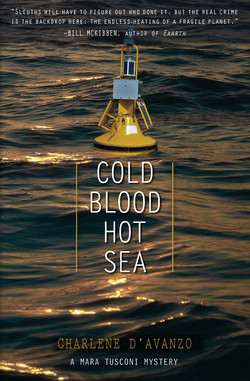

With her new red offshore racing jacket and blond hair, Harvey Allison was easy to spot on the stern deck. She peered up at an orange buoy that looked like a gaudy mushroom lying on its side—a ten-foot-tall, thousand-pound one.

I backed down the ladder to join her. My slippery old sou’wester made shouldering my duffel awkward.

“Dr. Mara Tusconi,” she teased. “Good morning.”

“Dr. Harvina Allison.”

Harvey reached up and ran her hand across bold black letters—MOI—Maine Oceanographic Institution. “It’s almost as if the buoys can’t wait to be released into the sea.”

I patted the instrument. “Just like we’ve waited all winter for the temperature data these babies will collect.”

Last year, ocean waters off Maine were the hottest in a hundred fifty years. Suddenly everyone who sold marine critters—lobsters, shrimp, eels—demanded to know what the hell was going on.

“Now maybe we’re more than nerdy scientists, Harv.”

“The future of Maine fishing? That’s high profile. Could be dangerous.”

“What—?” Intrepid’s engines came to life and drowned me out.

Atop roiling water, the ship pushed seawater aside. Soon we’d depart. Legs wide for balance, I made my way to the port side and grabbed a handrail crusted with salt. I licked a bit from my palm and grinned.

Salt. My mother always said there was extra salt in my blood, because both my parents were ocean scientists. I looked toward MOI. If they were alive, Mom and Dad would be on the pier waving good-bye. They’d be proud of me. But they never knew I followed in their footsteps.

The ship surged forward and pulled away from Spruce Harbor’s pier.

Harvey put her hand on my shoulder and interrupted my reverie. “Looks like a Winslow Homer painting from out here, don’t you think? You know, wooden piers around the bay, lobster buoys, tree-covered hills.”

The harbor blackened beneath a purple cloud. “Whoa,” I said. “Mr. Homer’s pissed off.”

Harvey stared at the darkening sky. In profile her perfect features—high cheekbones, classic nose, large eyes—were even more evident. Who’d guess she drove a truck, had a rifle on her gun rack, and loved to shoot bear?

“Harvey, what did you mean danger—?”

The ship lurched. I heard a groan, and turned in time to catch a glimpse of bright orange shift behind a hydraulic crane. It looked as if the buoy might roll straight toward the starboard railing, an enormous toy top. Three guys jumped like fleas on a hot plate to stop it.

“Secure the lines!” someone yelled.

Crewmen scrambled to get the buoy back into position and secured it with stainless-steel cables.

“Bizarre,” I said. “Gear that heavy not fastened tight?”

“Damn right. I’m first on the list to deploy,” Harvey said. “Mine better not be that contrary buoy. Let’s head down to our cabin.”

Between us and the lower-deck staterooms were two sets of steep, narrow ladders. I faced each one and clambered down. The rhythmic drone of the ship’s engine got louder and the stink of oil got stronger. By the time we reached our stateroom, diesel bouquet coated my tongue.

I threw my ratty duffel on the tiny desk next to Harvey’s brand new one. Intrepid rolled to port and threw me onto the bunk bed. My stomach lurched, and I tasted diesel.

“Crap. I checked the weather forecast a dozen times. It’s supposed to be calm until tomorrow. If the seas pick up, I’m in big trouble.”

“Have your seasick patch on?”

I touched the spot behind my ear. “Yes. Look, I’m going up to check the forecast. And my email.” I stepped out of the cabin, stuck my head back in. “Can’t remember. Have you deployed buoys this large in rough weather?”

Harvey ran manicured fingers through her champagne bob, and looked at me, her gray eyes steady. “I’ll be just fine.”

I stepped out into the passageway and turned back once more. “You said dangerous. What did—?” But Harvey had already shut the toilet door.

A half-dozen computers ran along one side of the main deck laboratory. I slipped into one of the mismatched chairs. My dear friend Peter, the youngest PhD on board, clicked away at the keyboard next to me.

“Hey, Peter. How’re Sarah and the twins?”

Focused on his computer, he furrowed his brow.

“Peter, what on earth’s the matter?”

He held both sides of the monitor as if it might take off and turned toward me. “Bizarre email here. Hold on while I read it through.”

I logged onto the NOAA weather site for the Gulf of Maine. A low-pressure system would bring squally weather faster than predicted. Winds fifteen to twenty knots, swells eight feet. My hand went to my stomach.

I skimmed my emails. The subject line “Climate Change Scientists Fudge Data” caught my eye. I leaned forward to read:

Email exchanges show climate change scientists create their own heat by cooking the data. The researchers’ words—“transforming the data” and “removing outliers”—prove what the Prospect Institute has long known. So-called global warming is a manufactured fiction.

I turned to Peter. “Are you reading ‘Scientists Fudge Data’?”

He swiveled his chair to face me. His dark eyes narrowed, black as the storm racing toward us. “Yeah. This one might get us.”

“But everyone knows the Prospect Institute nuts claim smoking isn’t a problem, there’s no acid rain, ozone isn’t depleted. They’re not a credible source.”

“They’ve hacked emails and quoted researchers’ words. Don’t you see? That’s entirely different.”

“Transforming data, removing outliers? That’s just statistical lingo for data analysis. It doesn’t mean we’re fixing the numbers!”

I reread the message and stared at him, speechless. Like an athlete’s doping scandal, this could ruin a scientist’s career in a heartbeat. And the harassment could be horrific. In Australia, climate change scientists had to move after radical deniers threatened their families.

“There’s something else, Mara. At the bottom of the email is a list of the ten hacked scientists. You’re number seven.”