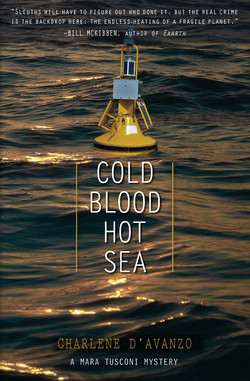

Читать книгу Cold Blood, Hot Sea - Charlene D'Avanzo - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

HARVEY AND I FROZE. MY scribbles were clearly visible on the whiteboard, and there was no time to erase them. As department chair, Seymour had keys to all the offices. Harvey pantomimed him putting a key into the lock. My mouth went dry.

We scrambled.

Seymour opened the door and walked in to find Harvey at my desk, earphones on, staring at a computer screen. I sat cross-legged on my yoga mat, eyes closed.

“Why didn’t you open the door?” he demanded.

Harvey pulled off her earphones. “What?”

I opened my eyes. “Seymour, what’re you doing here?”

“You didn’t hear me knock?”

“Guess I was in om-land.”

Seymour narrowed his eyes. He waved his hand at the whiteboard. “Rolling buoy, a bunch of names—what’s this?”

“Oh, that? Just what happened on Intrepid.”

“But why would—?”

Harvey interrupted him. “Do you always open office doors when nobody is inside?”

That took him by surprise. Harvey was always so polite.

He pressed his thin lips together and looked sideways at her. “Why do you think I have a passkey? I always knock first, but sometimes I need to check to see if everything’s okay. Any more questions?”

We stared at him.

“Good,” he said—and marched out.

I let go of the breath I was holding and looked up at Harvey. The hot pink, dangling earphones and wide eyes were too much.

My chortle morphed into a snort, and in seconds I was doubled up on the yoga mat, laughing like a lunatic.

I managed one “Harvey, I’m so, so sorry” in there somewhere.

Harvey couldn’t help herself either. She giggled and held her sides as tears streamed down her cheeks. She pulled a tissue out of the box on my desk, mopped her face, and said, “When he walked in, did you see his face?”

I crawled to the closest chair and climbed onto it. “Like he fell into Alice’s rabbit hole.” I grabbed a tissue. “But seriously, Harvey, you want to be department head and would be great at it. This is bad for you, and it’s my fault.”

She shook her head. “I chose to come back.”

“But Seymour—”

“Don’t worry about Seymour. I can deal with him. If I go for chair and he mentions this, who’d believe him?”

“Guess this shows what I’m doing is risky, at least where he’s concerned.”

“What we’re doing, girlfriend. Looks like I’m in it now.”

The surge of relief surprised me. I dabbed my eyes once more. “You’re one tough babe, Harv.”

After Harvey left, I walked over to my window. The floor to ceiling opening—a nod to the 1800s architecture of the original building—allows me full view across Spruce Harbor. A perfect place to muse. The bizarre incident with Seymour had helped me vent some tension. I took in a deep breath. Here I was about to go poking around, looking for answers about Peter’s death.

Was my decision to investigate only because, as I said to Harvey, Peter deserved an honest and thorough investigation?

Maybe it was more than that. Last night I stood before another window—Angelo’s—facing the ocean, and Peter’s death brought me back to a dreadful time.

I was nineteen. In an instant, both my parents had died. After the initial shock, I insisted that the incident was not an accident. My mom and dad would’ve checked that sub a dozen times and so would their pilot, someone they’d done similar dives with a dozen times. But the authorities wouldn’t listen to a grieving daughter.

I couldn’t investigate then. But I would now.

The list on my whiteboard was a start. Of the names I’d listed, Ryan was the most obvious person to talk to. But waiting a day was a good idea. Ryan was one of the kindest men I knew, and gossip that he’d intentionally harmed Peter pissed me off. Overwrought with guilt and shame, he was probably in his own hell.

I’d give Ryan a bit of time.

John Hamilton’s name was below Ryan’s. There were a few reasons why he might be a good person to start with. First, it was odd that he was on Intrepid since he wasn’t a scientist. Also, it was Seymour’s idea for him to come along. Given what Betty told me about Seymour’s past, that might mean something—or nothing. And Hamilton was on deck when the buoy fell on Peter. Maybe he saw something. Finally, John Hamilton owned an aquaculture company, something that genuinely interested me. That added up to four reasons to talk with him.

Tapping a pencil against my thigh, I tried to come up with a credible purpose for my visit to Hamilton’s facility. Maybe I claim to be curious about aquaculture. That was pretty lame. There must be a better excuse. My brain felt fried, and none came to mind. I needed food—something sweet. And Angelo had asked me to stop by.

I bought a quart of my favorite gelato—strawberry balsamic—and drove to his house. The latest Spruce Harbor Gazette was on the table in Angelo’s kitchen. I scanned the front page and waited for his take on the gelato.

Angelo looked at his bowl and wrinkled his nose. “Who puts balsamic vinegar in ice cream?”

The headline piece of the Gazette caught my attention, so it took me a few seconds to respond. “It’s good. Give it a try.”

He sampled a tiny bit. “Huh, you wouldn’t expect this to be so tasty.”

“Glad you like it. Did you see this?” I pointed to the headline—“Local Seaweed Farm Wins”—and slid the paper over to him.

Angelo dipped into the gelato again and leaned over to read the article. “Could be hype.”

“Yeah. Sunnyside Aquaculture successfully develops a super-seaweed. Maine scientists triumph. Etcetera.”

Angelo put down his spoon, leaned back in his chair, and crossed his arms. “With all that’s going on, why the sudden interest in aquaculture?”

I relayed what Betty had said about MOI, plus my disappointment with the Coast Guard’s inquiry.

He frowned. “I’ve known Betty Buttz for what, forty years? Hate to think of MOI like that. But she’s shrewd and might be right.”

“Betty suggested I explore on my own. Like she would. I thought I’d poke around, see if anything comes up.”

He eyed me. “And poke around means…?”

“I’m trying to figure that out. Basically, I’ll look into a few things.”

“Like what?”

I explained why it made sense to talk with John Hamilton. “The problem is I need a credible reason to go up there.” I glanced down at the Gazette. “This aquaculture place. It’s John Hamilton’s business.”

“So?”

“Here’s my reason. I’ll say I want to know more about the super-seaweed for my Oceanography class. You know, local sustainability ventures. Students love that stuff.”

Angelo ran his fingers through his hair. “Seems like a long shot to me, talking to this John Hamilton. What could aquaculture have to do with Peter’s death? But I don’t see what harm’s in it.”

I was up at five the next morning and seated at my office desk by seven. It hadn’t been the most restful night. Peter and I had discovered the Prospect Institute email only a few hours before the buoy debacle, and that crisis overshadowed everything else. During the night, worries about the email hacking and its implications for my career resurfaced with a vengeance.

I poked my head into the hallway. Ted’s door, five offices down, wasn’t open. MOI had lured Ted from Duke University because of his pioneering work on ocean acidification and marine organisms. We’d only spoken briefly on the cruise, but he seemed like a good guy and had offered to help me. This was my chance to get to know him.

I returned to my desk and emailed him.

Morning, Ted. Wondering when you’ll be in. I need the name of your contact at the Portland Ledger.

Three minutes later, he responded.

Be there by eight.

At 7:55, Ted walked in and placed a cup next to my computer.

“Thanks. What is it?”

“Decaf latte. I emailed you from the Neap Tide and asked Sally what you usually had.”

I opened the lid and sipped the milky brew. “Mmm…terrific.”

Ted carried a chair over to my desk and sat down. He wore a button-down blue cotton shirt open at the neck with the sleeves rolled up, jeans, and running shoes. With one hand, he pushed dirty blond hair up off his face. His tan set off startlingly blue eyes.

Once more, I envisioned Ted and Harvey as a striking couple.

I ran a finger down my ponytail and got stuck in a tangle halfway down.

“Haven’t seen you since we got back,” he said. “How’re you doing?”

“It’s hard. But Harvey and Angelo—he’s my godfather—they’ve been great. How ’bout you?”

“I told my parents what happened—they’re down in Boston. They try to be helpful but don’t understand.” He shrugged.

“If you need to talk, don’t hesitate to stop by.”

His smile was warm. “I might do that. You want my friend’s name. But tell me. The Prospect Institute email. What’re you most worried about?”

I swallowed. My mouth tasted metallic and dry. “The other scientists on the list are older and established. It’s my credibility as a researcher. You know, respect. Getting grants.”

“Colleagues know you haven’t cooked the data. But someone might believe it.”

“Or use it against me even if they didn’t.”

“Well, something’s just happened I’m guessing will sideline the Prospect Institute. A much bigger server hacking. Hundreds of emails between top climate change researchers from the U.S. and Britain.”

I felt giddy with relief and guilty that I did. “Damn. I haven’t seen the news yet. Still, I’d like to talk with your friend.”

“Bob Franklin.”

“Thanks. Maybe he could use Prospect’s reputation against them. The so-called revelations would backfire. Bob could explain what the out-of-context phrases really mean.”

“I like it. And so will he, I suspect.” He gave me Bob’s email and phone number, then stood. “I don’t think anything’s out about the Prospect Institute and climate researchers’ emails.”

“Some buzz on the usual denial blogs, but that’s it. So Bob might go for this.”

“Good luck. Gotta go. I’ve got papers to review and cruise data to look at.”

I thanked Ted, and he headed to his office. Things were looking up. Ted might become a friend, and the idiots at Prospect might get what they deserved.

I called the Portland Ledger and reached Franklin right away. He was excited about my take—how the Institute had turned our scientific conversations into nefarious-sounding smoking guns.

“The editor forwarded the email to me,” he said. “I looked at their website. It screams bias against climate change research. So I need to talk to scientists on the list. Really glad you called.”

A half-hour later, he had his headline, lead, and story. Instead of exposing climate change researchers as manufacturers of fiction, the Ledger piece would show how Prospect misused our words and phrases to promote their agenda. Done well, the article would educate people about the doubters.

“What about the other papers?” I asked.

“Nothing’s come out. I assume other reporters are doing the same thing. Checking the facts.”

I hung up, grinning. This was the first good thing to happen in days.

Two items topped my immediate to-do list: contact John Hamilton and work on the cruise data and NOAA proposal. I called Sunnyside to see if I could visit the following day. The aquaculture facility’s receptionist said Mr. Hamilton was out on the restricted pier—whatever that meant. Five minutes later he called back. No, tomorrow wouldn’t work.

I’d have to drive up there today.