Читать книгу Cold Blood, Hot Sea - Charlene D'Avanzo - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

MY STOMACH LURCHED, BUT THIS time it wasn’t the wild sea making me sick. “Why me? I’m not a famous climate change scientist.”

Peter said, “Maybe it’s your Science Today paper, and they’ve pegged you an up-and-coming troublemaker.”

The bitter taste of bile filled my mouth as the room closed in. “I don’t feel so great. Maybe we can talk later.”

Back out on deck, my stomach settled down as I gulped cold sea air. I tried to quiet the chaos in my head. Could a bunch of quacks jeopardize my reputation? I wasn’t an old silverback who could laugh off bad press. The funding I needed for research was hard enough to get. A scandal could be very bad news.

Peter might be right about my paper. I’d taken a chance with preliminary data and predicted unusually high temperatures in the Gulf of Maine this spring. As a young scientist, it’s hard to get noticed. The irony was my desire for attention could have endangered my whole career.

I leaned back against the railing and looked around. A half dozen crew and scientists circled the buoys, peering at instruments. Harvey’s deployment was soon, and I was on the list for the second one, after lunch. I tamed my long wind-whipped hair with an elastic band and twisted around. Twenty feet below, blue-green waves shot silver spray up the side of the ship.

Not good.

Someone bumped into me. A freckled redhead apologized, held out his hand, and pumped mine enthusiastically. “I’m Cyril, Dr. Tusconi. Cyril White. MOI photographer.”

A redhead with a name like that. Cyril must’ve suffered as a kid.

“So happy to meet you, Dr. Tusconi.”

I winced. Being called “Doctor” by a guy who looked sixteen made me feel my thirty-one years.

“Cyril, call me Mara.”

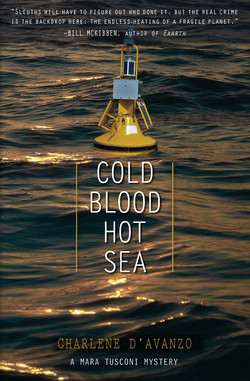

“Cy. Rhymes with lie. Hey, I’ll get better photos if I know what these buoys are for. I got the basics.” He pointed toward them. “One end’s the anchor, the orange float’s on the other end, and instruments on top and below measure things like water velocity and temperature. But what’s the purpose of this cruise?”

“To predict how ocean warming will impact Maine fisheries, we need measurements at more stations.”

“Why?”

“Fishermen want to know if the ocean’s warming. That impacts where and when they catch fish like cod. But Gulf of Maine temperatures vary a lot. The buoys give us better data, so we can judge if last year’s highs were an anomaly or the beginning of a trend.”

“Wow. This is a hot cruise. I’m psyched.”

This was a hot cruise, and I was proud to be part of it. That the Prospect Institute might tarnish work critical to Maine fishing sent a spurt of outrage through me.

Cy was still speaking. “I went to your talk on climate change doubters. I had no idea. They harp on ‘scientists aren’t sure,’ even though ninety-nine percent of experts agree—”

“Cy—”

This was the last thing I wanted to talk about at the moment, but the guy was on a roll.

“—the climate’s changing and we’re mainly the reason. They’re going after scientists. Does that include you?”

I felt like he’d punched me in the stomach. “Where’d you hear that?”

He shrugged.

Time to change the subject. “If you were in my oceanography class, I’d give you an A. Shouldn’t you be taking photos?”

He scampered off. For a photographer, he sure asked a lot of questions.

We’d reached the first deployment location. The engine droned down as the captain slowed Intrepid and held her steady on station. From the rear deck, Harvey shouted orders up to the winch operator. In her orange jumpsuit and yellow hardhat, she looked completely in charge. I gave her a little hand-pump.

The winch whirred, then kicked into a whine. Suddenly, a halfton buoy sprang to life and lifted off the deck. Shipmates and scientists worked the guy wires to keep the buoy steady as it slid to the stern before dipping into its new home at sea.

Cyril White, back pressed against a portable van, tried to switch between the camera around his neck and camcorder wedged between his feet. I walked over.

“Need help? I could hold the camcorder.”

“Yes! Could you shoot the video?”

Intrepid rolled and nearly tossed me into Cyril. Given the sea state, videotaping wouldn’t be smart. But this frazzled lad needed help. Cyril thrust the camcorder into my hands. I lifted the thing to eye level.

What the hell, I figured. It’s just a few minutes. I captured the orange blimp dangling from the crane, plunging into the sea, and popping up to whoops of the deckhands. In the water, the buoy looked like a half-submerged yellow R2-D2 topped with wind vanes and a couple of solar panel eyes.

Stupidly, I forgot a basic oceanographic physics lesson. Intrepid, now sideways to the waves, tossed port and starboard as well as fore and aft. I squinted through the viewer, trying to keep the bobbing buoy in the picture.

Bitter stuff oozed up from my stomach into my throat. I dropped the camcorder to my thighs, swallowed hard, took a deep breath, and lifted it once more.

The zooming back and forth with the camcorder did it.

I threw up. Bad enough. But I didn’t do it over the side. I doubled over and let loose right where I stood. I’d had cereal for breakfast so, well, it was a goddamn mess.

Finally, my gastrointestinal track was empty. Panting and coughing, I blinked open tightly scrunched eyes. Splattered boots came into focus. I prayed it wasn’t another scientist. Much better for a crewmember to see me in this thoroughly undignified condition.

I unfurled halfway. My splatter ran up yellow rain pants. Please be the deckhand who winked as I boarded the ship.

No such luck. I stood and looked into a chiseled face softened by wavy, straw-colored hair and lips turned up into a lopsided grin. Ted McKnight, my brand new colleague. Someone I’d really, really wanted to impress.

In a good way, that is.

He handed me a tissue.

I wiped my chin. “My god. I am so sorry.”

His clear blue eyes flickered with amusement. “Hey, not your fault. Hold on a sec.”

Ted skidded a water bucket my way, put his hands on my shoulders, spun me around, and splashed my rubber boots. I turned to face him, and he emptied the bucket on my boots and his pants. “There you go.”

Before I could retort with something clever, Ted walked away to deal with the buoys.

One of the crew mumbled, “Great. A seasick oceanographer.”

Ryan, first mate and my oceangoing pal, scowled at the seaman. “Enough.” He turned toward me. “Don’t you worry, Dr. Tusconi. We’ll take care of this.”

I climbed down the ladders to change. At the bottom, I missed a rung and landed with a thud at a crewman’s feet. I looked up into the liver-colored eyes of a ponytailed bruiser who didn’t bother to offer his hand.

“Ah, hi.”

“J-Jake.”

Jake walked away. If he were nicer, I’d feel sorry for a guy who stuttered his own name.

Sitting on my bunk, I stripped off the offending pants and pictured my excruciating moment with Ted. I pushed it out of my mind. No time for that now.

Back on deck, I closed my eyes and took in the cold, clean air. Intrepid was steaming straight now, heading for the next station.

The ship slowed to a crawl, and I popped my eyes open. The whistle sounded. Ear-splitting shrill—three short blasts—four times.

“Man overboard, port!”

I ran. The port railing was already three deep with scientists and crew. Crewmen below shouted as they lowered the rescue boat, but even on tiptoe I couldn’t see them. From the railing, Ryan pointed past the aft end of the ship. “There! He’s way back there!”

My mind raced through a grim list. If the man fell face down into the icy ocean, he’d reflexively gasp and flood his lungs with seawater. His blood pressure would spike. Then his heart would stop.

Frigid water was one reason why ship workers have the most dangerous job in the country. I put my hand on my chest and whispered, “God bless.”

Ryan yelled, “Level the damn boat and get in!”

Finally, the outboard roared and faded into a drone as the men sped toward their target, probably hundreds of yards off by now.

The boatswain shouted, “Turn to!”

The railing cleared, and I peered over the side. The inflatable was heading back, a bright red dummy sprawled on her deck.

Ryan joined me. He yanked down his cap and shook his head. “Much too slow a drill. Guys looked like rookies.”